19 Mar Here’s a bright idea should schools have to close: enlist childcare workers as nannies for health workers

As social distancing measures to restrain coronavirus become increasingly aggressive, one of the big points of contention is whether (and for how long) schools and childcare centres should be closed Danielle Wood and Nathan Blane propose some options

The prime minister says his best advice at the moment is that it is not necessary at this stage (although many private schools are choosing to close). One concern about closing schools is the potential of closures to devastate the health system as health care workers leave their posts to care for their children.

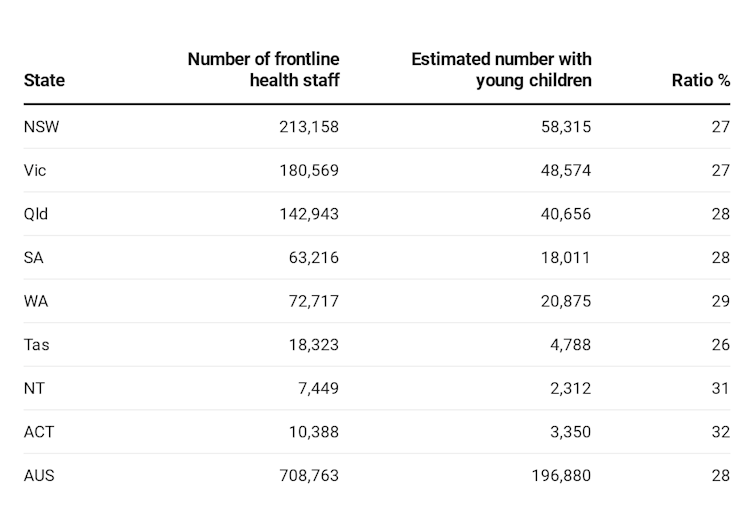

The disruption that would occur from the closure of schools around this country, make no mistake, would be severe. The prime minister is right to be concerned about the impacts on the health workforce. Our calculations, based on the Australian census, suggest 28% of Australia’s more than 700,000 doctors, nurses and aged care workers have young dependent children.

Losing even a fraction of them from the workforce at the peak of the crisis will cost lives.

We don’t want to lose health care workers

Many have partners who can care for children during the peak of the health crisis.

But some do not: there are about 45,000 households with children aged 14 or younger either headed by a sole parent who is a medical professional, or by two parents both of whom are medical professionals.

Source: ABS Census 2016

Many who might normally rely on their parents for support will want to avoid doing so, given older people are among those most at risk of serious COVID-19 infection.

So here’s a proposal to significantly reduce the human cost of school and childcare centre closures should they become necessary.

Employing child carers as nannies ought to work

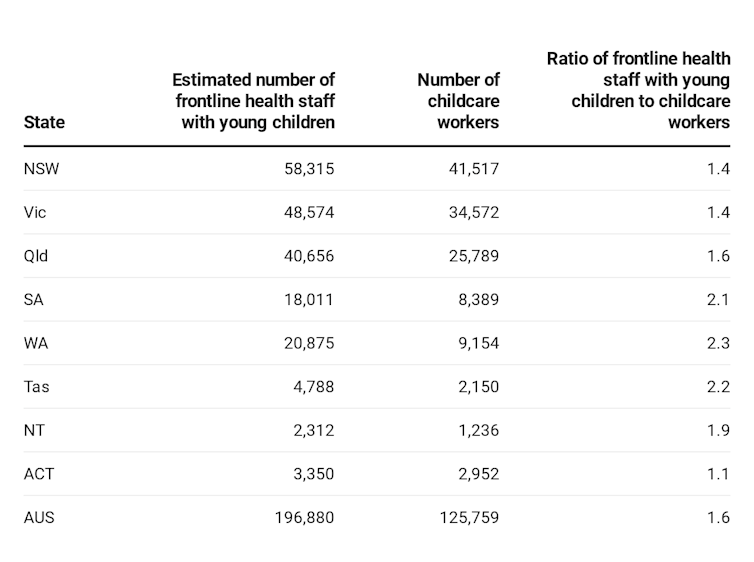

If Australia’s childcare centres are closed, more than 125,000 trained childcare workers, all with appropriate vetting, will not be working. The casual staff, in particular, will see their incomes dry up.

Our proposal is to redeploy childcare workers as nannies for the health care professionals who do not have alternative childcare support. This would keep the childcare workers employed and, most importantly, enable our health care professionals to keep working. We would be trading capacity of un-utilised childcare professionals for capacity of overextended medical professionals.

Across Australia there is one childcare worker for every 1.6 frontline health care workers with younger dependants, although this ratio varies substantially between states, and no doubt between different local areas.

But the bottom line is almost all health care workers who need help should be able to get it.

A downside is that health care workers are more likely than many other workers to be exposed to the virus, so their children might be at greater risk of infection.

This would increase the risk of infection for enlisted nannies. For that reason, all childcare professionals at higher risk of serious infection should be excluded from the scheme. No one would be compelled to participate, but for many childcare workers the promise of a stable income and the capacity to contribute to Australia’s health response is likely to be attractive.

Childcare workers who have their own children to care for should be able to take them along with them. In almost all cases, the number of children under the care of a single worker would still be far below the normal childcare centre caring ratios. Coordination and hiring of these frontline nannies could be arranged through the childcare centres themselves – all of which have staff well versed in rostering.

This plan is unusual, but we are living in unusual times.

Calling up our childcare workers to support frontline health workers would enable Australia to close schools and childcare centres should that be needed, and still give our health care system the best chance of treating those most in need.![]()

Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute and Nathan Blane, Analyst, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.