18 Jul Why is book removal so controversial?

Librarians have good reasons to ‘weed’ books from their shelves, report Sarah Polkinghorn and Lisa M. Given

Earlier this year, the removal of thousands of books to make room for renovations at Melbourne’s City Library prompted an outcry. Removing the books was “an absolute act of vandalism,” librarian Alice Bluer told The Age.

The City of Melbourne argued the space was needed for other in-demand uses, such as “community meetings, study and co-working”. The collection would be “refreshed”, taking into account “community feedback and borrowing trends”. Books not retained would be dispersed across the library network, donated or recycled.

Such disagreements bubble up periodically in the media, whether in schools or in national libraries. But where there are libraries, there is always “weeding”. Librarians select books for library collections, and over time, some of these books are deselected (or weeded) and removed.

As a practice, weeding is not quite as old as libraries. Famously, the ancient Great Library of Alexandria strove to be a “universal library” collecting all existing knowledge (on papyrus scrolls). But it existed in a profoundly different time when the knowledge we take for granted was only just being discovered.

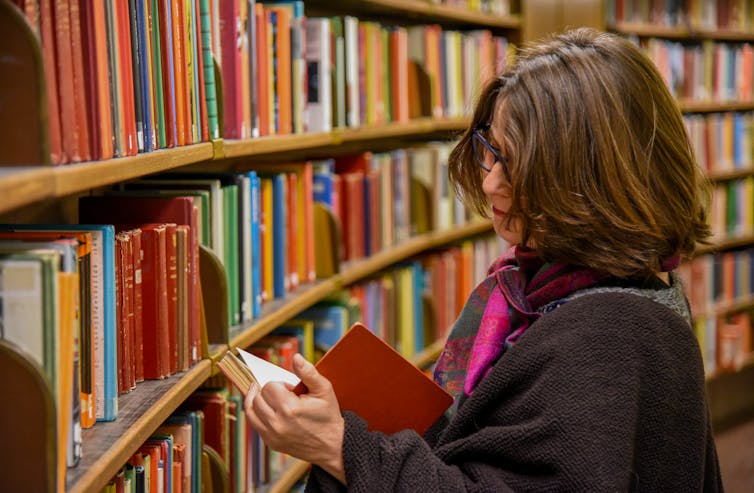

There can be too many copies of The Da Vinci Code. Amazon

With public libraries mandated to support literacy, recreational reading, and free access to information, today’s librarians make decisions about removing books amid competing pressures on their spaces and budgets. Even as libraries increasingly collect digital publications alongside print, weeding remains necessary.

But, as the recent Melbourne example shows, even professional librarians can disagree when difficult choices are made. So, what drives those decisions?

The books most likely to go

Books most likely to be weeded include:

- Duplicate copies. Public libraries often purchase numerous copies of hot, new bestsellers. While demand is high at the start, often with long lists of waiting readers, demand recedes over time. To create space for new titles, some copies (of, say, The Da Vinci Code) will eventually be deselected.

- Copies “loved to death”. Library staff want people to borrow books (and other materials, like games and magazines), to take them home, and enjoy them when riding the tram or train. Wear and tear are expected. People drop books in bathtubs, and yes, sometimes a dog will eat the latest Raina Telgemeier graphic novel. Worn-out or damaged books are often replaced.

- Copies that aren’t loved enough. At times, books fall out of favour with borrowers. Books that were once regular book club titles or were a hit with young readers now gather dust on the shelf. Librarians use professional judgement to weed out such books.

- Outdated books. In public libraries, consider how quickly technology manuals (Windows 95 for Dummies) or travel guides (Europe on $10 a Day) become out of date. In a university library, books supporting learning in medicine or engineering, for example—where the community needs state-of-the-art knowledge—may be replaced with new editions.

- Print copies collected in digital form. For more than 20 years, libraries have increased their collections of digital books. Many patrons now have e-readers and want to browse and borrow at home. Although digital books remain problematic in terms of licensing costs and publisher access models, they do enrich accessibility in important ways.

Libraries are for much more than reading and borrowing books. They are the hubs of their communities, providing spaces for children to study, language learners to attend conversation classes, job seekers to receive career support, people to try 3D printing, sewing, or mixing a record—the list goes on. All of these activities require a mix of rooms and open spaces, putting significant pressure on space for books.

Sadness and outrage

Weeding is often controversial. Even when books are weeded for good reasons, and despite libraries and librarians being highly trusted, public outcry is common. Reactions often range from sadness to outrage.

In 2011, major weeding projects at the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales resulted in a “mass book-borrowing action” by concerned students, with one critic comparing the weeding to “book-burning”. As with the recent Melbourne City Library case, weeding in these university libraries was being done to create space for other services and activities.

Unfortunately, these controversies are often only known to us through media reports, which cannot capture the complexities of each case.

Yet weeding outrage clearly reflects disagreements and misunderstandings about the nature of libraries, rooted in beliefs about their purpose. Weeding is a lightning rod for core concerns that run deep.

Many people continue to equate “libraries” primarily with “books” rather than understanding contemporary libraries as hubs for community connection, learning, literacy, safety, encounters with technology, and so much more.

Yes, books are at the heart of libraries. However, books are not the only things that matter in libraries. Libraries shoulder an ever-increasing, diverse set of responsibilities in their communities, patching holes in the social safety net and providing services to address social crises from misinformation to homelessness.

Meanwhile, the quantity of new books published annually continues to rise, now estimated between 500,000 and one million titles each year. Many of these books will be hotly requested, especially at local public libraries. Librarians must make tough decisions balancing book borrowers’ needs against many other demands on limited resources.

Books in bins?

Of course, one aspect of the weeding controversy is bigger than the libraries themselves. What happens to all those weeded books? One reason the Melbourne case made the news was the confronting idea of “recycled” books being trucked away to be turned into pulp.

While some books may be sold or donated to charity, the harsh reality is the number of weeded books headed to recycling generally far outweighs those that can be re-homed.

This is also true of unsold “remainders” in bookshops and of books people discard from personal collections. Despite the rise in little free libraries outside people’s homes at the height of the pandemic in Australia, many of these have now been replaced by little food pantries.

The optics of books being tossed into bins may echo concerns around book bans, which librarians have long fought against. But a key difference between the two is the reason why a book is being removed. Book bans are a violation of professional standards. But weeding a book is not censoring a book.

Librarians often compare collections across library systems so enough copies are available into the future. Weeding is governed by decades of professional guidance and upheld by international expectations for effective collections management. As the Australian Public Library Alliance and Australian Library and Information Association state in their guidelines for public libraries, “Collection size is not of itself a sufficient indicator of collection quality.”

The key criterion is whether and how the library serves the needs of its community. Libraries continuously evolve to support diverse needs today and for tomorrow.![]()

Sarah Polkinghorne, Research Fellow, Social Change Enabling Impact Platform, RMIT University and Lisa M. Given, Professor of Information Sciences & Director, Social Change Enabling Impact Platform, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.