30 Dec Fact Or Fantasy?

Katrina Germein wants her son to maintain a modicum of magic in his life.

…it is the fairy questions that I continue to find the hardest, perhaps because I’ve never really grown out of fairies myself. Perhaps because I know how important fairies are to my son.

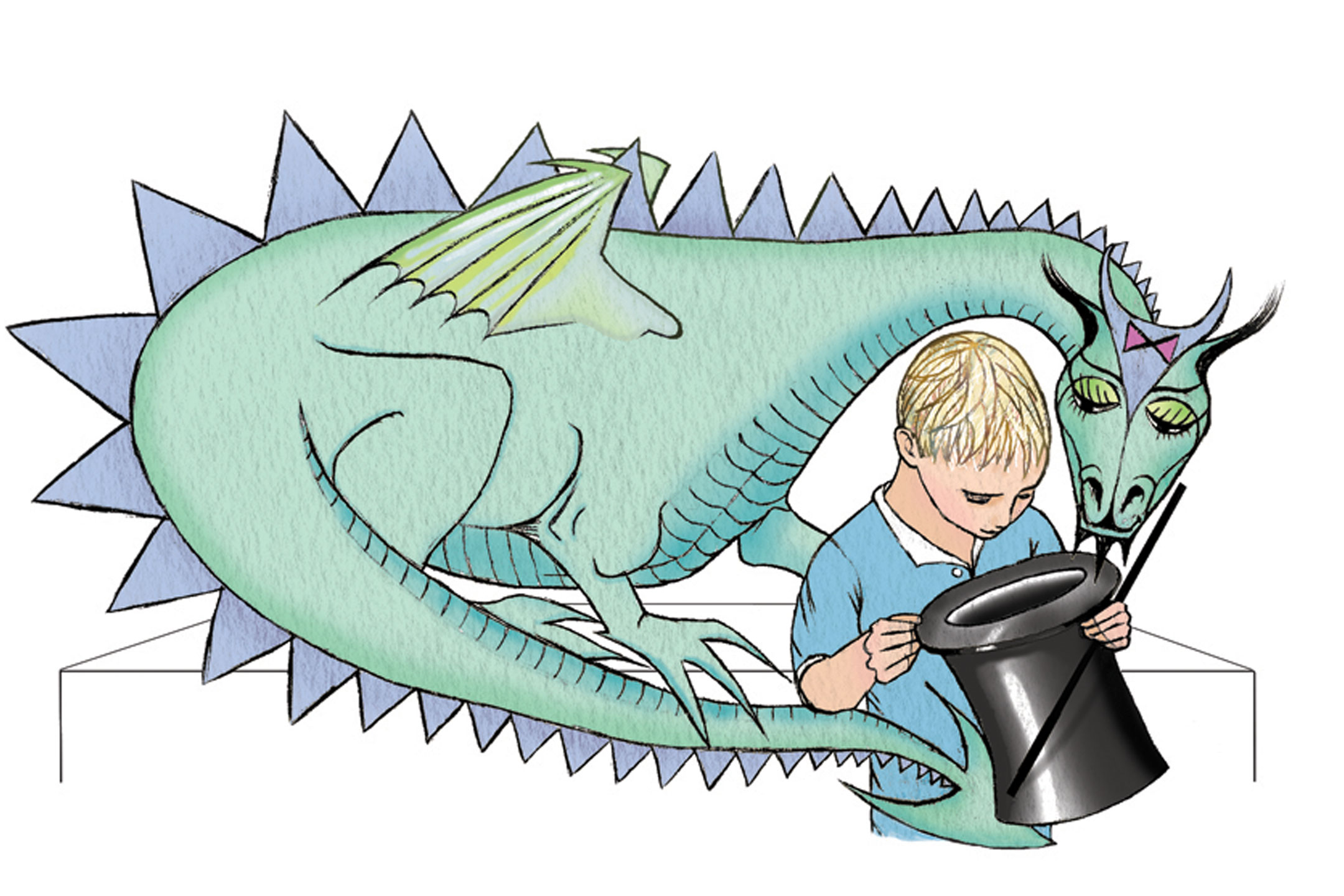

My six-year-old son believes in fairies – not only the tooth fairy, but an entire population of fairies living among scarlet toadstools in various fairylands across the world. He believes in glittery, pink-and-purple nymphs with sparkling wings, secret spells and magic wands. He doesn’t want to dress up like a fairy, or decorate his room with sparkly fairy things; he simply wants to believe that they exist. He also believes, of course, in Father Christmas and the Easter Bunny. My dilemma is how truthful I should be with my son, who trusts me absolutely, when he asks me direct questions about the truth of the magic in his world. “Are dragons real Mum? My Italian teacher said dragons are real so I know they are. There really are fairies, aren’t there Mum? Oscar said there aren’t, but I know that there are. Jack’s Mum said she’s seen one. I want a real magic wand, Mum. One that can do real magic. Like fairies have. And a real magic hat that things come out of.”

How and when do I explain to my sweet, earnest boy the facts about ‘real magic’ and gradually ease him into a world where it doesn’t exist? When is it okay to begin to dismantle his wonderful childhood place where fantasy is reality?

About six months ago, I was asked a different question: “Mum why is Humphrey not real? Why is he just a man in a suit?” “Who says he’s a man in a suit?” was my defensive reply. “Daddy,” was the answer. Fortunately, on account of my husband being more practical and less sentimental than me, we were able to establish that along with Humphrey, Barney, Bob the Builder, the Teletubbies and Wags The Dog are not real. We then tackled Sesame Street and concluded that its inhabitants are mainly puppets, and we also discovered that Pooh Bear is a cartoon character created from a story. Five seemed like an appropriate age to be making these realisations. But such characters are fairly powerless, so we weren’t yet addressing the realm of magic.

My mum tackled the ‘I want a real magic hat and wand’ question one morning before school, in what seemed to me to be a crushingly blunt fashion. “Well,” she said, “there is no magic, really. Just tricks. Magicians just do tricks to look like magic. There isn’t really any real magic.” “He has to know,” insisted Mum when she saw that my face was even more crestfallen than my son’s, who then asked me, “Is that true Mum? Is there really no magic?” Here was my chance to be honest, but it felt more like a chance to board up the door to a kingdom in the sky. “Um, well, that’s what Granny believes,” I answered.

So now we have a compromise. Even as my young magician practises his own tricks for an upcoming show (which he intends to perform in front of his grandparents with the video camera running) he still believes that not all magic tricks are tricks. This is a happy medium for now.

The Father Christmas questions are familiar to all parents. These are the easiest to answer because, in a sense – compared to, say, wizards and mermaids – Santa exists with his own parental rule book. We all know where he lives, what he does and that as parents we should try to encourage our children to believe for as long as we possibly can. (We also find that, come December, it’s very useful to remind our sometimes overexcited children that Father Christmas might be watching.) Santa comes complete with an entire catalogue of supernatural accomplices who are all bundled into something called ‘the magic of Christmas’. During the festive season, it seems okay to endorse flying reindeer, watchful fairies, toy-making elves and a magic sleigh. This is an easy lie to play along with because everybody does it. And, for most of us, although we can remember with supreme clarity the devastating moment when we found out Santa was absolutely not real, it was worth it for all the presents and excitement. Do we resent our parents for not being honest with us? No, although sometimes we still mourn that enchanting belief in a magic that we can’t recapture.

Shrek is my son’s favourite movie and he understands that most of it’s not real. We’ve talked about how it’s a fairytale like Cinderella and The Three Little Pigs. However, my son will not let go of the dragon. “Mum, I know Shrek’s not real and most of the things in the movie aren’t real, but dragons are real, aren’t they?” I have been brave and strong in my response to this. I have explained that dragons are mythical creatures and we have spent some time discussing the meaning of ‘mythical’. However, like my mother’s explanation of magic tricks, my son isn’t ready to accept this. He has conceded that maybe the dragon in Shrek isn’t real, but he believes that other dragons are.

During the school holidays, I took my three children to see an outdoor performance that starred fairies, elves, a fairy queen and a dragon. My six year old was most excited about seeing the dragon. After all, we know that fairies and elves are real – this would prove that dragons were real too. The papier-mâché dragon turned out to be about the size of a horse, an endearing rusty-brown colour, with a friendly face and long-lashed eyes. Anchored to one spot, he could only move his neck up and down, and when asked a question, he made a few muffled noises. He did not flap his wings or blow fire and so I thought that this might be a gentle end to the belief in dragons. The debate in the car proved that I was wrong. “See, Mum? Dragons are real. Now you know they are because you’ve seen one. Do you believe me now?” My four-year-old daughter responded before I could. “That wasn’t a real dragon. It was just pretend. Like a puppet or something that someone made.” For her, telling the difference between fantasy and reality isn’t a problem. While she loves all things ‘fairy’, she can enjoy a fantasy without having to be reassured that it’s real. On a recent walk through the Botanic Gardens, she insisted on stopping to put a hat on her favourite doll, “so she doesn’t get sunburned”. “But she’s just a doll,” protested her twin brother. “Yes,” was the response, “of course she’s a doll, so she can’t wear sun block and that’s why she needs a hat.”

Dragons not fully dealt with, my six-year-old son and I tackled Spiderman the other day, something I found remarkably easy to do. “Mum, does Spiderman have spinnerets in his bottom so he can make web?” “No,” I replied, “I think Spiderman makes the web come out of his hands.” “But how?” “Because Spiderman’s not real.” Done. Easy. I felt no remorse. And my son wasn’t particularly worried.

But the fairy questions I continue to find the hardest, perhaps because I’ve never really grown out of fairies myself. Perhaps because I know how important fairies are to my son. “How can we get to fairyland? Have you ever seen a fairy? Why are fairies very little? How come they can fly and we can’t? They are real, aren’t they, Mum? Aren’t they?”

Is it hurting my son if he believes in little magical people who spend the day singing, dancing and making happy spells? Does it matter if, for a little bit longer, he can hold onto the belief that the world holds magic and secrets that we can’t always see and explain? Well, I’ve decided that it doesn’t. And I’m going to let my son keep his fairyland for as long as he wants.