09 Mar What can be done about the excessive promotion of gambling to our young?

From TV to TikTok, young people are exposed to gambling promotions everywhere, report researchers Simone McCarthy, Hannah Pitt and Samantha Thomas

I’ve walked past two TABs pretty much weekly, because one’s near our ice cream shop and one’s next to the shopping centre. So, we go there a lot.

This quote from a 12-year-old girl in our latest research shines new light on young people’s exposure to gambling in their everyday lives. The 11- to 17-year-olds who took part in our study told us they regularly come into contact with gambling not just during sports, but in a range of everyday environments.

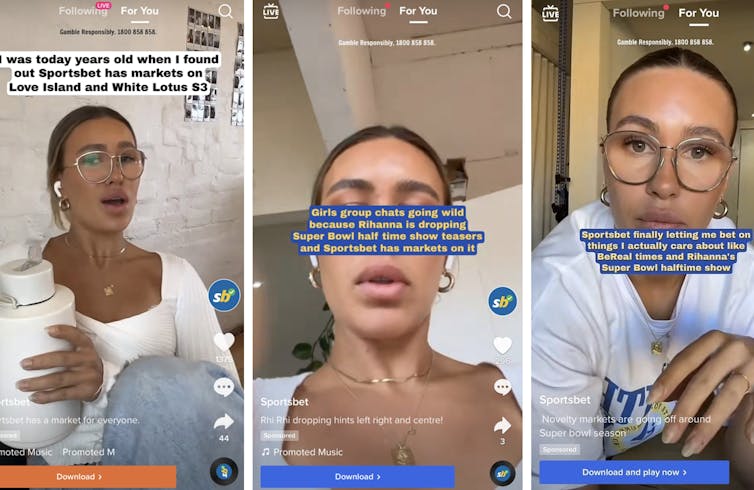

They saw promotions for gambling in local shopping centres, at post offices, during sporting matches, movies and television shows. They were also aware of a range of novel products and marketing strategies the gambling industry is using to reach the next generation of customers.

‘It must be something normal’

This constant exposure created a perception gambling was “always there in your face” and “a natural thing to do”. This was particularly the case when it was placed alongside non-gambling activities in everyday settings. As one 16-year-old boy told us:

I think just the number of ads and there’s posters up for it around shops. […] It makes it seem, because it’s everywhere, it must be something normal.

Author provided

While the excessive promotion of gambling in sports has been a catalyst for public concern, governments have largely failed to act. Rather, it appears they have decided the harms and costs associated with young people being exposed to gambling marketing are outweighed by any benefits to the gambling industry, sports (through sponsorships), and broadcasters (through advertising revenue).

There is also little publicly available evidence that school programs or public education campaigns run by organisations such as the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation are having a significant impact, or that they are able to compete with the might of commercial marketing strategies. The gambling industry’s own “educational activities” are at best useless, and may well be counterproductive.

@pointsbet/instagram

How young people engage with gambling ads

Our research shows the clear impact of gambling marketing on young people. They are able to name gambling brands and can quote taglines and slogans. They report seeing different types of gambling promotions in sports, and on a range of popular television shows, including “Gogglebox” and “MasterChef”.

Young people also said they see gambling promotions “pop up in my feed” on social media sites such as Instagram and YouTube. As a 15-year-old boy told us:

[I see them] on YouTube before I watch a video. A funny Sportsbet skit comes on. It’s not about gambling though […] I see them when I watch highlights, too.

Our research also shows that inducements such as free bets and celebrity promotions have a particular influence on young people believing that gambling is a “risk-free” activity and the promotions they see can be trusted.

Is change possible?

However, there is a clear opportunity for change. The current Parliamentary Inquiry into Online Gambling is investigating the effectiveness of gambling advertising restrictions on limiting children’s exposure to gambling products and services.

Our own submission to the inquiry has argued for strong government restrictions and bans on marketing, with a key goal of protecting young people.

While such restrictions are opposed by a range of stakeholders, including sporting organisations, broadcasters, advertisers and sectors of the gambling industry, there is clearly growing public and political support for gambling marketing bans, including from young people themselves.

In developing robust policy responses to gambling, another issue needs to be addressed.

Recent revelations about donations from online bookmaker Sportsbet to the now- minister for communications, Michelle Rowland, before the 2022 federal election have also raised legitimate concerns about mechanisms to protect gambling policy from commercial and other vested interests.

This includes the extent to which we can trust the policy decisions that are made about gambling. This is especially important when considering policies that are concerned with the health and wellbeing of young people.

What do young people think is the way forward?

The young people in our research share similar views to public health experts when it comes to strategies to protect them from the predatory tactics of the gambling industry.

They are critical of “responsible” gambling messages, which they say are designed to absolve the gambling industry and governments of their responsibility for harm prevention. They tell us governments should be responsible for action, including

- reducing the accessibility and availability of gambling products

- making gambling products safer

- removing gambling from sport, through regulation and sporting teams ending partnerships with gambling companies

- implementing strong restrictions (including bans) on marketing, and

- using public education to counter commercial messages about gambling, and provide honest information about the tactics of the gambling industry.

There is an “exceptionalism” surrounding government policies on gambling, in which gambling is not seen as needing the same robust public health policy response as other issues. A docile approach by governments that sees gambling as being somehow different from other unhealthy products must change if we are to see effective, evidence-based approaches to gambling harm prevention.

Effective measures to protect young people from gambling marketing will inevitably be opposed by the gambling industry and its allies. But young people, parents and the community understand the cause for concern and the need for action that will genuinely curb the promotional activities of this powerful but predatory industry. ![]()

Simone McCarthy, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Deakin University; Hannah Pitt, VicHealth Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Deakin University, and Samantha Thomas, Professor of Public Health, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.