29 Jul Why Schools can’t close the education divide between the big cities and the rest of Australia

Don’t expect schools to do all the heavy lifting to close the education divide between the big cities and the rest of Australia, writes Professor John Halsey

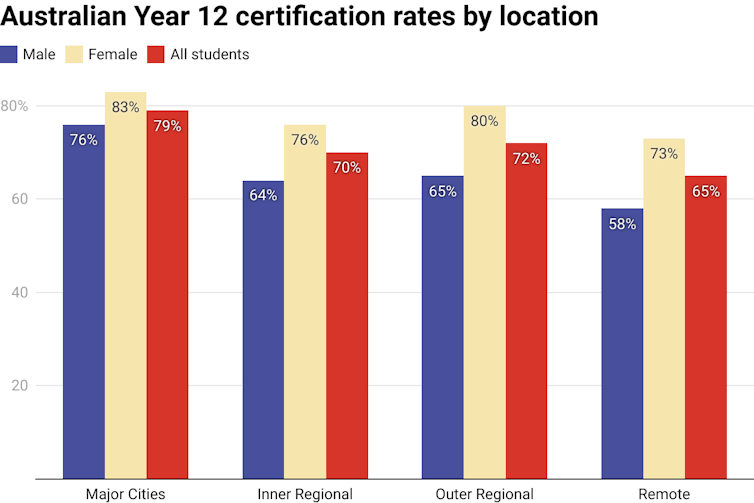

Students in regional, rural and remote Australia have been behind their urban counterparts on almost every recognised measure of successful schooling for decades. This is unacceptable and has to change.

To achieve this change, it will be vital to draw on and build the neglected capacities of parents, families and communities to improve student achievements at school. The National School Reform Agreement between the Commonwealth, states and territories aims to lift student outcomes across Australia. But the current five-year agreement, which runs to the end of 2023, almost entirely ignores the lives of students outside schools.

The world outside the school fence is where students spend most of their time. What’s happening and not happening there directly impacts their motivation and ability to learn. Education policies and practices have to embrace this reality.

Schools can’t do it all on their own

Now under review by the Productivity Commission, the next National School Reform Agreement will have to respond to the diversity of school locations and communities, especially in regional, rural and remote areas. It should include a strong focus on building the capacity of these communities to help improve learning.

To date, we have seen the intensification of schooling via curriculum changes, micro-managing teaching and learning, and growing accountability and administration workloads. It’s clearly not working for students in regional, rural and remote areas.

All the pressure has been on schools to do the heavy lifting. That’s neither sustainable nor effective.

The review is an opportunity to radically rethink what needs be done to close the schooling gaps across the country.

Local disadvantage feeds into schooling

The 2021 Dropping Off The Edge report by Jesuit Social Services looks at disadvantage around Australia. Little has changed since the last Dropping Off The Edge report in 2015. Most disadvantaged communities are in regional, rural and remote locations.

The report reveals, yet again, the profound effects of poverty, family disruptions and conflict, and an absence of hope and positive role models on achievements and opportunities beyond school.

Most efforts to improve education across the board have focused on what happens in schools. These efforts include modifying what students learn, changing assessments, varying teaching methods, increasing ICT and more.

While this work needs to continue, there is more to be done. Student achievements and opportunities are shaped by a diverse blend of in-school, home and community factors, the interactions between them and knowledge of what is happening in the wider world. For some students this productive dynamic is missing, or operates minimally.

The reasons are many and varied. They include poor health and diet. It is very hard, perhaps impossible, for students to focus on learning if they feel hungry and are often unwell or “out of sorts”.

These difficulties are compounded if their home life is stressful and chaotic, there is a long history of unemployment and underemployment, and another problem always seems to be just around the corner.

In short, what’s going on outside the school fence has a large impact on what happens in school. It’s time to release this handbrake on students reaching their potential.

Policy ignores what goes on outside schools

The Productivity Commission is reviewing three reform directions in the National School Reform Agreement:

- supporting students, student learning and student achievement

- supporting teaching, school leadership and school improvement

- enhancing the national evidence base.

For each of the reform directions there are national policy initiatives. These directions and initiatives are very school-focused.

The agreement does not refer at all to the contributions that parents, families, communities and social and personal relationships make to student achievements. The diversity of learning contexts and locations, especially in regional, rural and remote areas, is also mostly invisible.

Ignoring what is going on and continuing to ramp up pressures on schools to do all the heavy lifting will lead to the next Dropping Off The Edge report in five years’ time again showing little or no change.

It’s time to focus on community solutions

The next National School Reform Agreement must include a strong focus on community capacity-building to improve learning.

This is fundamentally about tapping into existing opportunities or creating new ones to make students’ out-of-school lives richer, more optimistic, more stable and better supported for learning.

Where multiple disadvantages are at play, capacity-building requires sensitivity and persistence to develop local expertise and resilient working relationships with individuals and families. Critically, what is learnt needs to be fed back into reforming systemic policies and practices.

In addition to education experts, this means drawing on health services, enterprises and employment, justice and policing, local governance, parents and residents, linked to each school or cluster of schools.

Flexibility is essential as community capacity-building can vary enormously on the ground. It might involve individuals or small teams of trusted adults who are 24/7-go-to people “no matter what”, or start-up enterprises such as local construction and hospitality programs linked to tourism opportunities, or music and arts events, and more.

Sport can play a vital role, particularly when participants are recognised and valued for more than being a good player.

Enlisting young people to become skilled emergency volunteers is another way to build the capacities of individuals and communities. This training can be a bridge to formal learning.

Community capacity-building requires substantial long-term funding. Importantly, local improvements produce many offsetting benefits by boosting school completion rates, employment, health, local optimism and general well-being, while reducing youth crime and incarceration.

Education that fully engages young people and nurtures and builds their capacities throughout their formative years is a very sound investment. It will be repaid many times over a lifetime.

This article is part of The Conversation’s Breaking the Cycle series, which is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation.![]()

John Halsey, Professor, School of Education, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.