26 Oct Do hypoallergenic cats even exist?

Susan Hazel and Julia Henning dispel 3 myths about cat allergies

Cats are great companions, but for some people their company comes at a cost. Up to 1 in 5 people have an allergic response to cats, and this figure is increasing.

There are many myths about allergies to cats, but what is fact and what is fiction? And can you still have a cat if you’re allergic?

Myth #1: People are allergic to cat hair

There is an element of truth to this myth. However, rather than the hair itself, substances on the hair are the source of the allergy. Most people allergic to cats react to a protein called Fel d 1. This main cat allergen is produced in the glands of the cat, including the sebaceous (oil-producing skin glands) and salivary glands.

While Fel d1 is the main culprit, domestic cats have eight different potential allergens. The second most common is Fel d 4, also produced in salivary glands.

Another type, Fel d 2, is similar to a protein found in other animals, and the reason a person might be allergic, for example, to both cats and horses. This similarity can also result in a child with milk allergy having an increased risk of being allergic to animals like cats.

When cats groom themselves, they deposit the allergen in their saliva onto their hair. Sebaceous glands are close to the skin and can secrete onto the hair follicles. When you pet a cat’s fur, a reaction is set off, especially if you then rub your nose or eyes.

But you don’t need to pet a cat to have an allergic reaction to them. Simply being around dander can be enough. Dander might sound like a dating app for pets, but it’s actually more akin to animal dandruff, and contains tiny scales from hair or skin. As dander particles are so small, they float in the air and we often breathe them in.

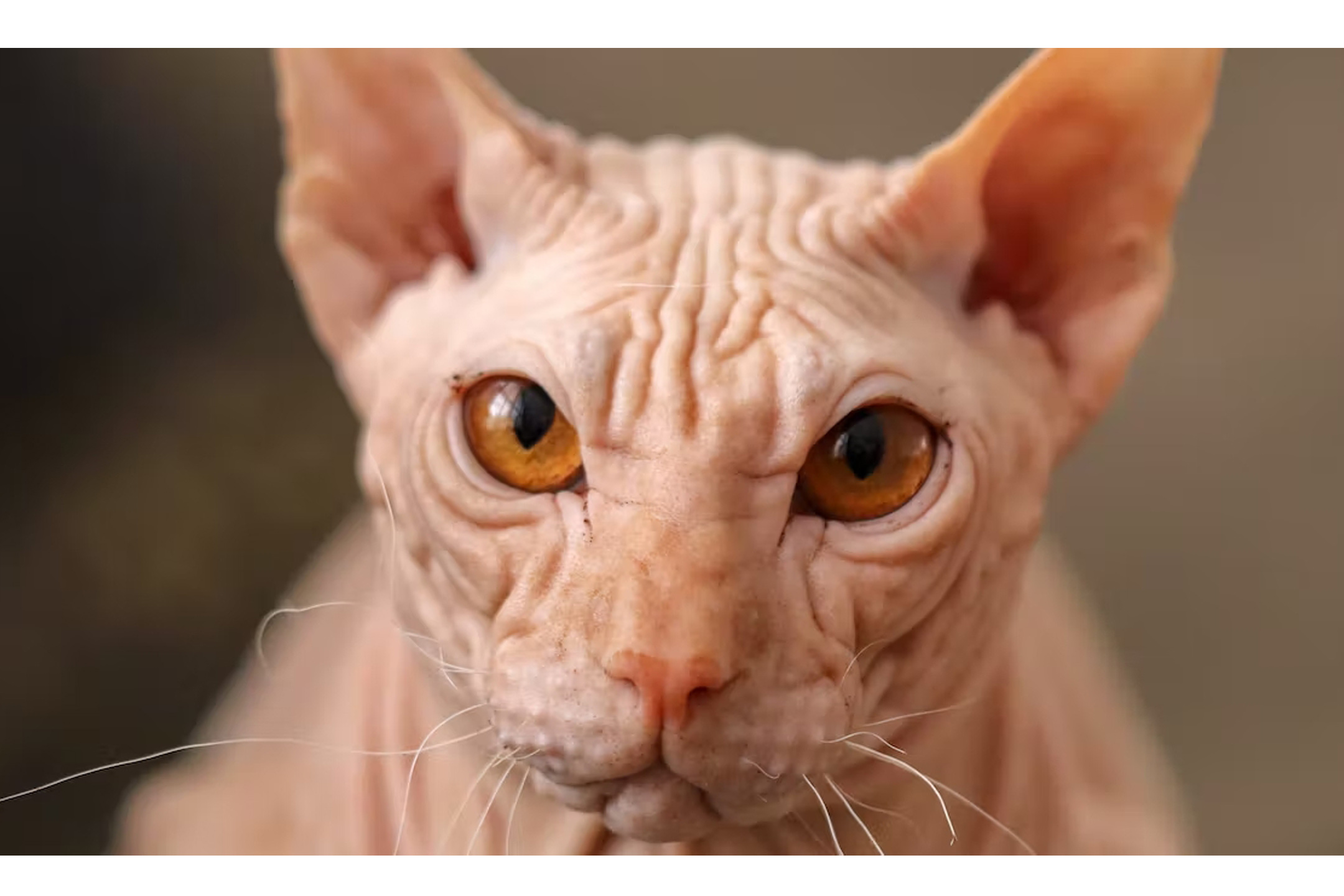

Myth #2: There are hypoallergenic cats

There is no evidence that specific cat breeds do not cause allergies. However, if some breeds have less hair, or shed less hair, this may reduce exposure to allergens in the environment.

For example, Sphynx cats are hairless, although they still produce Fel d 1. In this way some breeds might be considered “hypoallergenic”, or cause fewer allergic reactions. However, there are no scientific studies to confirm this is the case.

All cats produce Fel d 1, but the levels can differ by as much as 100-fold between individual cats. This may explain why people with cat allergies notice they react more to some cats than others.

Jesus Vivas Alacid/Shutterstock

Myth #3: You have to re-home your cat if you have an allergy

If you have a life-threatening allergy to cats, your only alternative might be to find them a new home. However, most people have less severe reactions and can manage symptoms successfully.

Some things you can do to limit reactions include:

- always wash your hands and avoid touching your face and eyes after handling your cat

- regularly clean surfaces and change litter to reduce dander

- wash your cat weekly with a pet-specific shampoo, if your cat likes being bathed

Matyas Rehak/Shutterstock

- restrict cats’ access to rooms you want to keep allergy-free, such as the bedroom

- get a vacuum specifically designed for reducing allergens, such as ones with a HEPA filter

- use air purifiers with HEPA filters.

Adopting a cat when allergic

If you’re allergic and want to adopt a cat, make sure to spend some time with them first to assess your reaction. Ideally, pick a cat that doesn’t make you sneeze.

If cats need to be re-homed, this does negatively affect their welfare. A large study of RSPCA shelters in Australia reported allergy as the reason for relinquishment in roughly 3% of cats out of 61,755 total relinquished between 2006 and 2010.

You can also see your doctor about options for managing symptoms such as over-the-counter medications (such as antihistamines) and longer term solutions.

For those with allergies who want to have their cat and their ability to breathe too, another option is immunotherapy, although there is limited evidence to support this treatment for cat allergies.

Immunotherapy involves first identifying which specific allergen is causing the reactions, and then systematically delivering increasing levels of this allergen over several months in an effort to retrain the immune system to tolerate the allergen without a reaction. This may be especially beneficial for those with moderate to severe reactions.

There is evidence exposure to dogs and cats early in life can reduce at least some forms of allergy. Evidence is still conflicting, though, and probably depends on genetics and other environmental factors.

What we do know is that pet cats provide companionship and joy to many, and understanding the causes and treatment of pet allergy can only help both cats and humans.![]()

Susan Hazel, Senior Lecturer, School of Animal and Veterinary Science, University of Adelaide and Julia Henning, PhD Candidate, University of Adelaide

Main Image: Sergey Belsky/Shutterstock

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.