12 Mar What books are kids reading in Australian schools – and does it matter?

Debates about what books students should be reading in high school reach a crescendo at the start of each school year, writes Alex Bacalja

As parents make their way through school text lists, collecting books for their teen’s year ahead, they inevitably draw comparisons between their own school reading and the literature selected for their children by teachers, schools and mandated curriculum.

Some are astounded their teens are still reading the same books they read at school.

Everyone has an opinion

One father of a Year 9 daughter wondered on Twitter last week, at the start of the 2023 school year, why she was assigned the “boring” Animal Farm, Romeo and Juliet and Wuthering Heights. (His original post was so flooded with responses, he became overwhelmed and deleted it.)

Some of his fellow parents agreed an all-classics diet threatened to turn teens off reading, and called for older texts to be replaced with contemporary ones that reflected teen lives. Some raised the diversity problem of the so-called – mainly white male – “canon”. And others called for a blend of classic and contemporary books, to tick all the boxes.

But everyone had an opinion.

Compulsory schooling has done extraordinary things for our collective skills and knowledge. But one of the consequences of requiring almost everybody to complete a secondary education is that it has become common, even natural, for adults to hold strong beliefs about the “right” kinds of literature that should occupy school time.

In the social media age, it is easier than ever for parents to share these views. Their concerns are also tied up in almost perpetual anxiety about young people and their futures.

Diversity backlash

These anxieties have not been helped by political leaders who capitalise on the opportunity to politicise the school curriculum for the purposes of leveraging their opponents and stoking their bases. Whenever attempts are made to read and study texts in the English classroom that reflect the diversity of Australian society – and within Australian classrooms – the backlash is intense and sustained.

When former Prime Minister Tony Abbott appointed staunch conservatives to review English in the Australian Curriculum, the resulting report was awash with racist commentary about the “wrong kinds of literature”, and called for a greater emphasis on Western literature.

More recently, attempts were made by New South Wales legislative council member Mark Latham to amend the Education Act, so that teachers who taught gender fluidity – including through the selection of texts with gender fluid characters – would be sacked.

These examples demonstrate the precarious grounds upon which teachers must make decisions about which literature is best for their students.

What are they reading at school?

Concerningly, no research has ever been conducted in Australia to collect reliable data about what a typical high-school reading list contains. This means almost all of the discussion about the content of teen reading in schools is based on observations, anecdotes and presumptions.

We do have a good sense of what students might be taught.

The Australian Curriculum, along with the various state iterations of that guiding document, makes suggestions about the types of literature students should be exposed to: classic and contemporary world literature, including texts from and about Asia and First Nations people. And about the forms literature should take: novels, poetry, short stories and plays; fiction for young adults and children, multimodal texts such as film, and a variety of nonfiction.

However, specific titles are not identified in these documents. Senior (Years 11 and 12) English and Literature curricula across Australian states and territories provide more guidance, with most jurisdictions providing highly restrictive lists from which teachers must select texts for their classes.

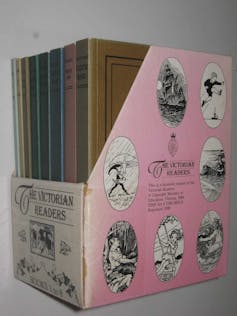

Some of the limited evidence we have from the past and present suggests we have a long way to go to produce reading lists that reflect contemporary realities. For example, Demond Gibbs studied the content and use of school books in Victoria between 1848-1948.

ebay

The early School Papers (1896-1928) tended to privilege British content, reflected conservative social views, were Royalist in tone, and included a small selection of Australian authors. The 1928 shift to the Victorian Reader, a series of eight books commissioned by the Victorian Education Department, reflected a strong sense of Australian nationalism and far less emphasis on empire. Titles included: John and Betty, Playmates, and Holidays.

More recent research suggests “traditional” literary texts remain the bedrock of senior school reading. One study of ten years of Victorian Senior English texts lists found Indigenous literature is rarely included in these lists and prescribed lists don’t reflect our diverse society. Almost 10% of all texts listed are from the writing of William Shakespeare, John Donne, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Charles Dickens, Charlotte and Emily Bronte, and Ernest Hemingway.

Another study reported that in New South Wales, the rec

Research also suggests there is an almost total lack of opportunity for students to read and study digital forms of literary work in the senior years of schooling.

It appears those lamenting the death of the classics have nothing to fear.

ImDB

Why does it matter?

Given we don’t really know what students are reading in schools, and the world has continued turning on its axis, does this really matter?

On the one hand, it matters greatly. Schools have a powerful role: consecrating some stories and knowledges at the expense of others. As renowned French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu established across decades of research, schools and education systems are fundamental tools of state. They actively contribute to the production of certain types of “cultivated” people.

The inclusion and exclusion of literary works is just one way this tool operates. This cultivating has its foundations in ideas about so-called classics.

Arguing about the texts teens will read at school is a perfect example of what Emeritus Professor Bill Green calls “the representation” problem.

Since we cannot fit the entire world into the classroom, we must use the curriculum to select which forms of life to represent. Discrimination is inevitable and always political. This discrimination is evident in decision-making about which children’s picture books receive awards, just as much as controversies about narrowly selected judging panels for adult literary awards.

Katerina Holmes/Pexels, CC BY

Adding all texts and all textual modes to school reading lists is impossible. The challenge is for teachers and other stakeholders to be honest about the current state of affairs and priorities – and to also reflect on what might be missing and in need of attention.

Australian schools have been lucky to avoid the waves of book-banning spreading the US. The most recent iteration bans African American studies and even the use of the word “gay” in classrooms.

Such bans reflect highly outdated and uninformed views about how children read and the purpose of literature in schooling.

It’s not what they read, it’s how they read

Another way to approach big questions about reading at school is to focus less on what is selected, and more on how these texts will be taught.

The conflation of literature and literacy has meant the content of school reading has contributed to an ignorance, at least outside school staff rooms and teacher training courses, of the importance of reading pedagogies: the methods of instruction teachers use when modelling and supporting reading at school.

School reading is about much more than the recitation of details related to characters, quotes and story events. The many reading approaches a teacher can deploy makes it difficult for parents or politicians to judge the validity of a particular text selected for study.

These approaches might include, for example, reading for pleasure, reading to explore identity and questions of belonging and alienation, or reading (and writing) to understand social media and the explosion of digital culture.

Despite the failure of standardised tests like NAPLAN to improve school outcomes, and evidence we do not need high-stakes and high-stress exams to determine end-of-year scores for year 12s, the narrow forms of reading dominated by these approaches crowd out space for rich and diverse school reading.

Trust teachers

We must be honest with each other and recognise we don’t really know whether reading literature makes us better people.

I am reminded here of Franco-American literary critic and philosopher George Steiner. He questions the idea high literacy can civilise individuals, by reminding us of those SS officers who would spend their evenings listening to Bach and Schubert and reading Goethe and Rilke, then go to work at the Auschwitz concentration camp in the mornings.

It would be wonderful if school reading could help heal us, process our emotions and develop empathy.

For now, we must put our faith in English teachers. We must trust them – without interference – to select texts for our teens. They know how literature can support the learning needs of their students better than anyone else. And they have spent their entire working lives specialising in the craft of teaching and supporting reading.![]()

Alex Bacalja, Senior Lecturer, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.