31 Aug Censorship or sensible: is it bad to listen to Fat Bottomed Girls with your kids?

Liz Giuffre, asks should children be exposed to music with questionable lyrics?

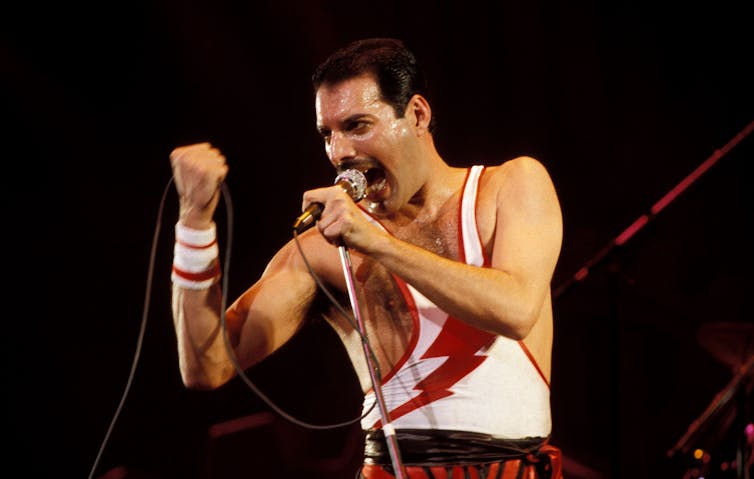

The international music press has reported recently that Queen’s song Fat Bottomed Girls has not been included in a greatest hits compilation aimed at children.

While there was no formal justification given, presumably, lyrics “fat bottomed” and “big fat fatty” were the problem, and even the very singable hook, “Oh, won’t you take me home tonight”.

Predictably, The Daily Mail and similar outlets used it as an excuse to bemoan cancel culture, political correctness and the like, with the headline “We Will Woke You” quickly out of the gate.

Joke headlines aside, should children be exposed to music with questionable themes or lyrics?

The answer is not a hard yes or no. My colleague Shelley Brunt and I studied a range of factors and practices relating to Popular Music and Parenting, and we found that more important than individual songs or concerts is the support children are given when they’re listening or participating.

A parent or caregiver should always be part of a conversation and some sort of relationship when engaging with music. This can involve practical things like making sure developing ears aren’t exposed to too harsh a volume or that they know how to find a trusted adult at a concert. But this also extends to the basics of media and cultural literacy, like what images and stories are being presented in popular music and how we want to consider those in our own lives.

In the same way you’d hope someone would talk to a child to remind them that superheroes can’t actually fly (and subsequently, if you’re dressed as a superhero for book week, don’t go leaping off tall buildings!), popular music of all types needs to be contextualised.

Should we censor or change the way popular music is presented to kids?

There is certainly a long tradition of amending popular songs to make them child or family-friendly. On television, this has happened as long as the medium has been around, with some lyrics and dance moves toned down to appease concerned parents and tastemakers about the potential evils of pop.

Famously, Elvis Presley serenaded a literal Hound Dog rather than the metaphorical villain of his 1950s hit.

In Australia, the local TV version of Bandstand from the 1970s featured local artists singing clean versions of international pop songs while wearing modest hems and necklines.

This continued with actual children also re-performing pop music, from the Mickey Mouse Club versions of songs from the US to our own wonderful star factory that was Young Talent Time. The tradition continues today with family-friendly, popular music-based programming like The Voice and The Masked Singer.

In America, there is a huge industry for children’s versions of pop music via the Kidz Bop franchise. Its formula of child performers covering current hits has been wildly successful for over 20 years. Some perhaps obvious substitutions are made – the cover of Lizzo’s About Damn Time is now “About That Time”, with the opening lyric changed to “Kidz Bop O’Clock” rather than “Bad Bitch O’Clock”.

In some other Kidz Bop songs, though, references to violence and drugs have been left in.

Other longer-standing children’s franchises have also made amendments to pop lyrics, but arguably with a bit more creativity and fun. The Muppets’ cover of Bohemian Rhapsody, replacing the original murder with a rant from Animal, is divine.

Should music ever just be for kids?

Context is key when deciding what is for children or for adults. And hopefully, we’re always listening (in some way) together.

Caregivers should be able to make an informed decision about whether a particular song is appropriate for their child, however, they consider that in terms of context. By the same token, the resurgence of millennial love for The Wiggles has shown us no one should be considered “too old” for Hot Potato or Fruit Salad.

When considering potential harm for younger listeners, factors like volume and tone can be more dangerous than whether or not there’s a questionable lyric. Let’s remember, too, that lots of “nursery rhymes” aimed at children are also quite violent if you listen to their words closely.

French writer Jacques José Attali famously argued the relationship between music, noise and harm is politics and power – even your most beloved song can become just noise if played too loudly or somewhere where you shouldn’t be hearing it.

As an academic, parent and fat-bottomed girl myself, my advice is to keep having conversations with the children in your life about what you and they are listening to. Just like reminding your little superhero to only pretend to fly rather than to actually jump – when we sing along to Queen, we remember that using a word like “fat” and even “girl” isn’t how everyone likes to be treated these days.![]()

Liz Giuffre, Senior Lecturer in Communication, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.