02 Nov Early childhood educators are slaves to the demands of box-ticking regulations

Early childhood educators are slaves to the demands of box-ticking regulations, writes Marg Rogers, University of New England

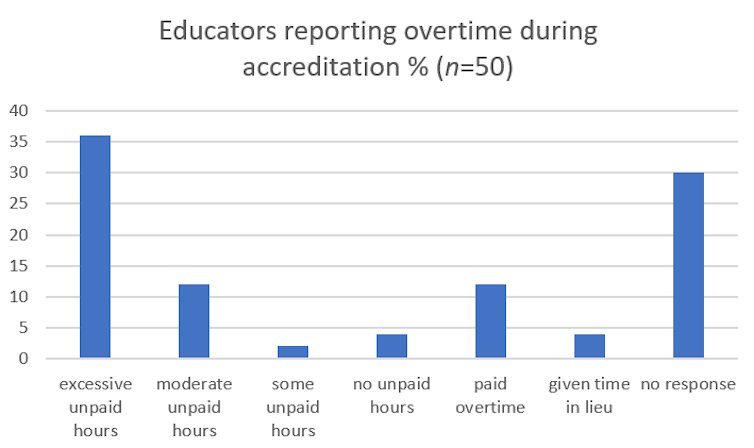

More than two-thirds of Australian early childhood educators reported working many extra hours to satisfy regulatory requirements in our 2021 survey. Half did unpaid work during accreditation — the process of demonstrating compliance with all the regulations governing early childhood education. Some were paid for as little as half of the hours they worked.

It’s not like they were well paid in the first place. Early childhood educators are the 13th-lowest-paid workers in Australia.

These educators earn an average of $29.10 an hour. Workers with the minimum of a certificate in childhood services are more likely to earn $23.50 an hour, while those with a diploma or degree earn more. Unqualified workers in male-dominated industries earn far more than workers in the female-dominated early childhood sector.

The stresses of low pay and long hours cause almost one in three early childhood educators to leave the profession each year. This year, a survey found 73% intend to leave the profession in the next three years. Providers are struggling to find qualified staff.

Long hours of unpaid work are common

I’m involved in a transnational study exploring the work of early childhood educators in Australia, Canada and Denmark. The Australian data include survey responses from 50 educators from a range of service types in cities and regional and rural settings.

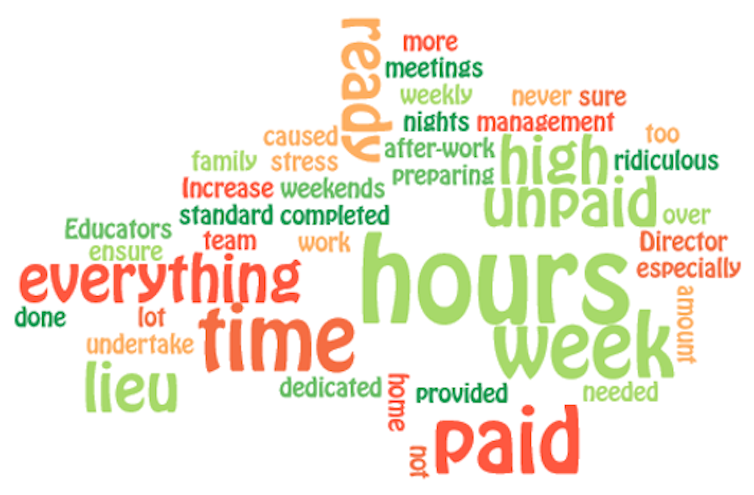

Some 70% commented on how many extra hours they worked during accreditation, with 50% reporting unpaid hours. Educators said:

“I work a 68-hour week yet get paid for 30 hours.”

“a lot of unpaid hours.”

“Staff were given work to fill in whilst on breaks, often stayed back for unpaid staff meetings and to do extra work.”

“lots of unpaid work to catch up on the documentation that was required”.

To be accredited, services must provide state regulatory authorities with documentary evidence they are meeting or exceeding the measures of quality laid down by the Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). Some participants said the demands from these rigorous quality checks have become “ridiculous”, requiring volumes of documentary evidence.

Preparing this evidence requires time away from the children, whose development depends on quality interactions with their educators. Many said they could not do the documentation in working hours because they were busy teaching children and supporting families.

Why do educators do the extra work? If the service doesn’t pass, it triggers more checks, requiring more frequent documentation. Very few educators said they were paid for this extra time.

When commenting on the number of unpaid hours, some noted the impacts on their family life:

“Too many. It caused stress at home with family.”

“We dedicated over 2 weeks of nights and weekends to be ready for accreditation and registration. Even our husbands came and did work with us.”

“Detrimental. Lack of work life balance during this time.”

Author provided

Attrition is creating staff shortages

With unfair wages and increased expectations due to COVID-19 health orders, many providers are struggling to staff their services. Research shows educators leave the profession when they can no longer afford to stay.

As quality education and care depend on interactions with individual children, their families and communities, staff turnover is of great concern.

Yet, rather than tackling these issues, the increase in managerialism in Australian education has added to the stresses of poor pay for a demanding job.

What are the impacts of managerialism?

Managerialism creates a system where the worker is positioned as someone who is mistrusted.

In these systems, workers are given highly detailed descriptions of tasks that need to be checked by managers and authorities. Rather than doing the job they were employed to do, workers find themselves busy producing data to show they are following these instructions.

Managers and authorities say this is necessary to ensure quality. Their beliefs about quality are transcribed into voluminous documents. Often these documents are so complex, even longer documents or guides are provided to decipher the original document.

In early childhood education, these include curriculum documents, frameworks and standards. The Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) creates these documents. State and territory regulatory authorities are responsible for ensuring compliance through registration and accreditation — a process of assessment and rating.

Quality may actually suffer

Many educators believed accreditation requirements lowered the quality of education and care during accreditation. One said:

“It is a joke! Everything is so inhibited, and the children and educators are far too over-regulated. The children cannot be free to learn. They cannot go near water, they cannot climb. Fear is instilled into the educators. It is a horrible and restrictive learning environment. It makes the children so small-minded and full of anxiety.”

An ACECQA survey this year found educators intending to leave the sector early blame overwork, administrative overload and burnout.

Have authorities unwittingly created an accreditation system that enslaves workers and reduces quality during accreditation periods? Further research is needed to discover the full burden of these compliance systems.

What now?

What can we do about this discovery of excessive unpaid wages and chronic underpayment of our essential workers? Being a slave is defined as being part of the slave trade, but also includes those who do not receive proper remuneration for their work. With a federal election looming, it is another matter to lobby our government about given Australia’s uneasy relationship with slavery.

To recover strongly from the economic impacts of the pandemic, we need strong workplace participation. To support this participation, real reform is needed to provide universal childcare and fully staffed services. The focus must be on creating systems that support quality education and care, not big data and slavery.

Marg Rogers, Lecturer, Early Childhood Education, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.