17 Jul Looking at Difference: Selective Mutism

Klay Lamprell explains that selective mutism is now understood to be a form of severe anxiety, rather than a sign of a stubborn or manipulative child.

Even as a baby, Danielle Dawes was extremely shy. She would turn her head away if anyone looked at her and would never cry in front of people other than her family. By the age of two, she was talking at home but would not say a word outside the house. At preschool, her lack of communication made it clear that something was wrong.

“It wasn’t just not talking – she also wouldn’t eat when they handed out plates of sandwiches or whatever, because she didn’t want to grab,” says Danielle’s mother, Anna. “The teachers used to say she was being stubborn and that she was trying to run things, so they wouldn’t give her what she wanted – pencils or toys – unless she would eat or talk. They weren’t cruel. They just thought she was trying to control them. I just thought she was very shy. My husband was very shy as a child, my brother was extremely shy and I am very quiet. But then just before she started school and still wasn’t speaking, we became worried.”

The psychologist hadn’t heard of it

Anna’s doctor couldn’t help and neither could the psychologist she finally consulted. In frustration, and suffering the constant ‘advice’ of well-meaning friends, Anna started to do her own research.

“I found information on selective mutism. The psychologist hadn’t heard of it, but when she looked into it, she said yes, that seemed to be it.”

The psychologist suggested that Anna try to access a school-based pilot program being developed by clinical psychologist Maria Milic for children with selective mutism, aged four years and up.

Interestingly, parents will often describe the child with selective mutism as the most talkative member of their family

“Selective mutism is thought of as children who have the ability to speak and comprehend language, but who fail to speak in select social situations,” Maria says. “They will speak freely and comfortably to members of their immediate family within the family home, and there are other environments where they will comfortably use their voice to communicate, so they are not totally mute. Interestingly, parents will often describe the child with selective mutism as the most talkative member of their family, saying that the child ‘never stops talking at home’.”

She will speak to her family when her brother’s friends are visiting but she won’t talk directly to the friends

Danielle speaks to her mother and father, her 10-year-old brother and a few members of the extended family. She will speak to her family when her brother’s friends are visiting but she won’t talk directly to her friends. Anna says, “He gets tired of his friends asking why his sister doesn’t talk and sometimes he’ll say to Danielle, ‘Why won’t you just talk?’”

Until the 1980s, the condition was called ‘elective mutism’ because it was considered to be a choice the child was making not to speak, and it was frequently viewed as oppositional or manipulative behaviour. According to Maria, research now shows that a child’s consistent failure to speak in select environments is a result of severe anxiety and not a conscious decision.

“The name was changed to ‘selective mutism’ to reflect the research showing that the behaviour of failing to speak was not because they were being naughty or difficult or controlling. They are children who are severely worried or anxious about speaking. They may worry about how their voice will sound, or what people will think of what they say, or of drawing attention to themselves. They use avoidance of speaking as a strategy to manage their extreme anxiety.

A diagnosis is often not made until the child is at school

“Anxiety has a physiological component to it. …When the children can explain it to me or to their parents, they say things like ‘the words get stuck’, or they feel like there is something horrible in their tummy, or their heart is beating very fast. When you’re really anxious you’re in a state of panic. You may not even hear what is being asked of you.”

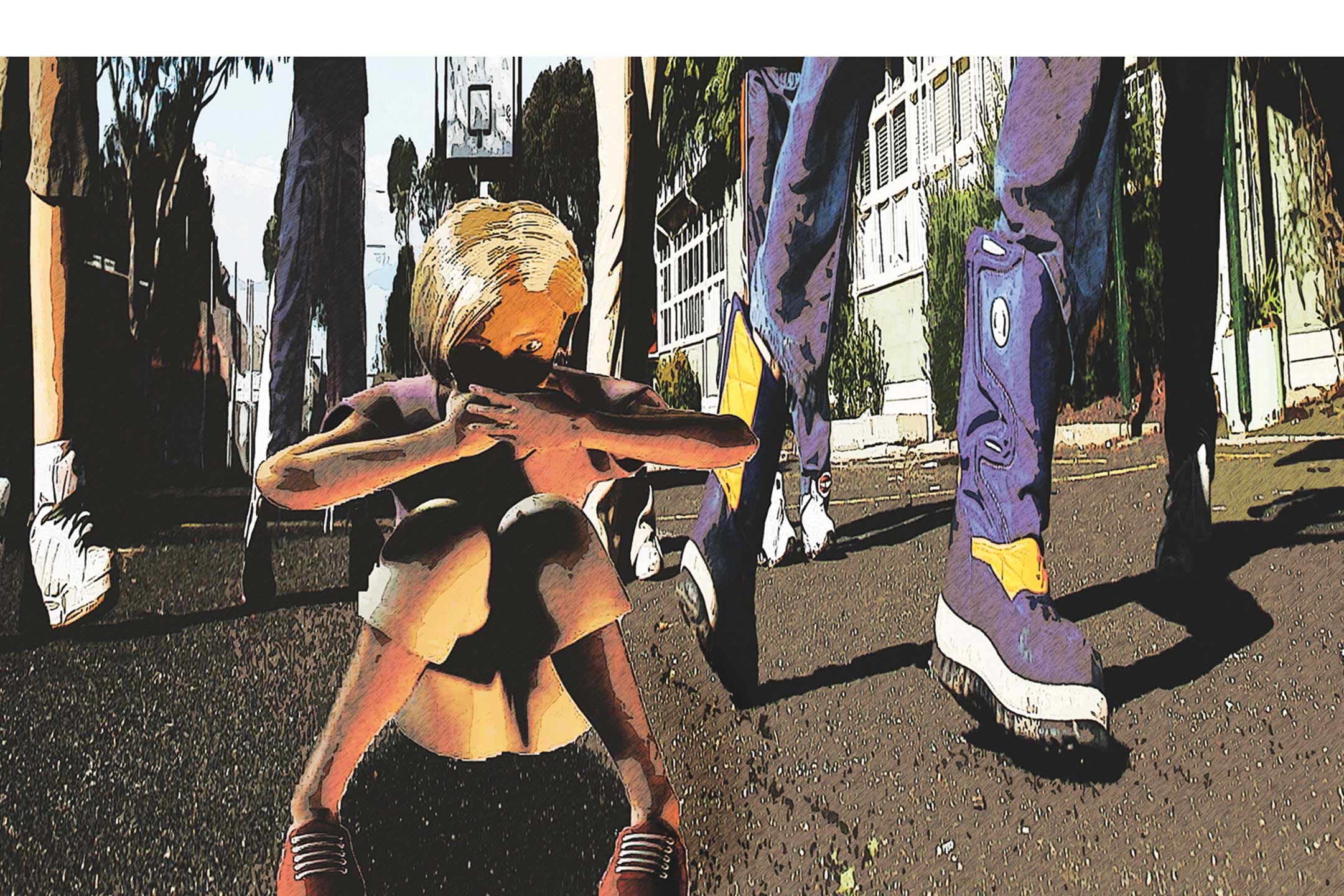

Maria notes that a diagnosis is often not made until the child is at school. “Very young children can’t articulate anxiety. Instead, they may turn away or hide, fidget or show other anxious behaviours. At an early age, this is understood as shyness. So when a child is thought of as shy, it may not even be until the child’s second year at school that parents become seriously concerned about their lack of verbal communication outside the home.”

Gradual exposure to situations that cause child anxiety is typical of treatment programs for anxiety disorders. Maria’s program introduces the element of play to help children feel comfortable. “We have short sessions three times a week with the teacher, parent and child within the school environment. We focus on interactions the child will enjoy and we aim for small goals. If a raised eyebrow is the only form of communication the child can manage, that’s what we go with at first. Then we gradually increase the goals and generalise the achievement into the classroom setting. It is important not to focus on getting the speech out, but to make them comfortable about being less shy in each session. It is a program that asks a lot of teachers but I’ve found schools to be very supportive.”

Over the next two years, Maria will attempt to quantify her success rates. “Taking into account school holidays and other interruptions to the program, it takes about twelve to eighteen months and sometimes longer before a child will feel comfortable speaking in all situations within the school grounds. When they find their voice, they tend not to relapse back.”

Asking a child with selective mutism to talk is similar to asking a person with a phobia of heights to bungee-jump off a tall building.

Selective mutism specialist Dr Elizabeth Woodcock, who uses the play-sessions concept in her therapy, sees children from preschool age. “The lack of awareness of selective mutism is concerning, yet recent research suggests it is more common than autism. What is most concerning is that if the condition is not identified early and adults don’t realise that the child’s lack of speech is caused by anxiety, their reactions to the child can often make the condition worse.

For example, a child who doesn’t talk at preschool but starts chatting to their parent as soon as they walk out of the gate is easily seen as stubborn, rather than anxious. This perception can understandably lead to feelings of frustration for teachers, which, if detected by the child, can make it more difficult for them to talk. These children are sometimes ridiculed or are given consequences for not talking, and we know now that this makes the condition much worse. Even gentle encouragement to talk at times when the child is highly anxious can make the mutism more entrenched. Asking a child with selective mutism to talk is similar to asking a person with a phobia of heights to bungee-jump off a tall building.”

Elizabeth notes that a common misconception is that the mutism is caused by trauma. “In fact, we know that it is at least partly genetic. In almost all cases, parents would describe themselves as shy or as having some level of anxiety, or having a relative who was extremely shy as a child. We have so little research to base our understanding on, but since about a third of children with selective mutism have speech impairments, it is conceivable that these kids have an anxiety issue from a very early age, and then they talk and someone laughs at them or no-one understands them, and they link their anxiety with speaking.

There has been some success with anti-depressants

“Sadly, the prognosis for children who do not receive treatment is not great in terms of mental illness, social isolation and academic achievement as they get older. Yet their intelligence is no different from the general population. And when they are young – if they don’t also have social phobias and separation anxieties – they often have friends and are accepted amongst their peers.”

Elizabeth believes that in some situations, medication can assist the process of treatment. “Anti-anxiety drugs such as Valium are addictive and we develop a tolerance to them, so they wouldn’t typically be given to children. However, there has been some success with anti-depressants.”

Maria also notes that studies on the use of medication in conjunction with therapy have suggested good results. “There have also been trials using medication alone to good effect. What we don’t know yet is whether that is complete remission or whether that is a small improvement in the amount of talking. It is important that parents ask all the questions they have about medication to allow them to make an informed choice.”

After five years of treatment, Anna has started Danielle on medication. “I was hesitant, but we’ve done everything we can. We’ve been in therapy a long time and we’ve come a long way, but then not really. It is very frustrating.”

Anna says that in the past few weeks since Danielle has been on medication, she has spoken to a shopkeeper for the first time and has started whispering some words to a girlfriend. “Definitely the medication is helping,” says Anna. “I know there may be side effects but with medication and therapy, I think Danielle will talk.

“I just wish there was more information for people about where to go for help, and a group to get in contact with for support because there are days when you just want to give up. You need reminding, especially on the days when it’s not going well, that you are doing the best you can.”

For more general information on this rare condition see the article in Psychology Today