09 Feb Maternal metamorphosis: how mothering has changed in Australia since the second world war

When I first became a mother in 2013, Carla Pascoe Leahy reports, I realised my experiences of motherhood did not match the kinds of messages circulating around me.

As a society we talk about motherhood either in cheesy sentimentalities – think of gift catalogues for Mother’s Day – or in terms of how overly burdensome it is for women. Too often, we depict motherhood as a problem or a crisis, rather than considering whether there are ways that mothering enriches a woman’s life.

Psychologists recognise becoming a mother as a fundamental shift in a woman’s identity.

So, I decided to try and understand this metamorphosis of the self that I recognised in myself, to track how it has developed over time, and what it can tell us about motherhood today.

By interviewing more than 60 Australian women who entered motherhood between 1945 and the present, I’ve created an oral history of how it feels to become a mother. While each interview is unique, together they form three broad eras of generational experience.

Postwar mothers

Women who had their first child in the 1950s and 1960s had a distinctive experience I call postwar motherhood. During these decades, Australians embraced plans for marriage and parenthood that had been delayed by the second world war. Under conditions of full employment and high male wages, many families could live on one income.

In 1954, for example, only 15% of married women were in paid work. Most girls grew up assuming that their identity would centre on motherhood and for many, that meant becoming a full-time housewife. Women became mothers at a younger age and had larger families: almost half had their first child in their early 20s and mothers had 3.5 children on average.

When I asked postwar mothers whether motherhood had changed them, many were dismissive. Eve felt that “I was the same person but growing in skills” and explained that – like many Australians in the mid-20th century – she did not analyse herself very often.

Museums Victoria

Postwar mothers were characteristically stoic in remembering motherhood. By contrast to living through the Great Depression or the second world war, they tended to downplay the challenges of toilet training or infant feeding.

However, a minority admitted finding the transition to motherhood difficult. Grace, for example, became “seriously depressed” from “managing two babies, and being isolated all day”. It was hard to speak openly about perinatal depression in an era when mental illness was considered shameful and the condition was not widely understood.

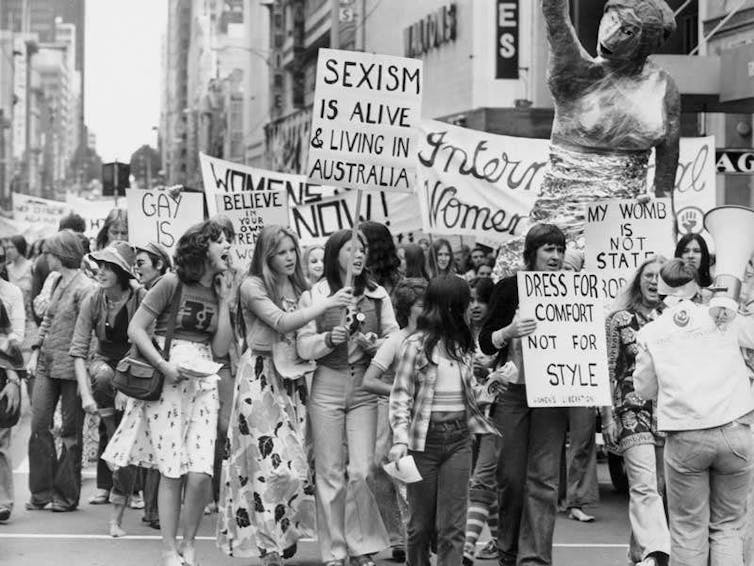

Second-wave mothers

Women who had children in the 1970s and 1980s had their experiences shaped by second-wave feminism.

More and more Australians came to believe a woman’s potential reached beyond breeding and raising children. Better access to birth control, abortion and sex education gave women a greater ability to control reproduction. The average age of first-time motherhood rose to 25 in 1971, and women were having 2.1 children on average by 1976.

Women’s participation in the labour force grew from 34% in 1961 to 62% by 1990, supported by the slow expansion of paid childcare.

Museum of Australian Democracy

There was growing discussion of psychology and emotion, as feminism encouraged women to speak about personal experiences, including mothering. Many second-wave mothers felt they were changed by having children. Susan said “having the first baby made my whole life worth living” and “fulfilled something that I didn’t know I needed”.

Second-wave mothers were franker about the difficulties of first-time motherhood. Sally found her initial experience was “hell on earth” and a “shock to the system in every way”. While Sally’s difficulties were short-lived, some mothers experienced more serious and long-lasting emotional struggles.

Miroslava remembers her sister Mary’s perinatal depression. Mary’s mother-in-law told her “it’s nothing” and “you’re being silly”. In an era when mental illness was stigmatised, Mary’s family was determined that “no daughter-in-law of ours was going to be diagnosed with a mental issue” and impeded her access to support services.

Mary’s story highlights the tragic incomprehension of many people towards perinatal depression in earlier eras. It also demonstrates that difficulties coping with motherhood do not happen in a vacuum, but rather in social contexts with many contributing factors.

Millennial mothers

Women who have become mothers from the 1990s to today I call “millennial mothers”. The influence of feminism means motherhood is viewed as a choice, and around one-quarter to one-third of Australian women alive today will likely never have children.

Those that do are having children later, with the average age of first motherhood rising to 31. Australians are also having smaller families. In 2020, the average number of births per woman was 1.8. Our gender norms have fundamentally shifted: millennial mothers have grown up assuming female identity is rooted in career.

Our cultural ideals of the “good mother” have also changed: from judging mothers who go out to work, to judging women who stay home with their kids. Assisted reproductive technologies have enabled motherhood where it would have been difficult or impossible before, for single mothers, lesbian mothers and for women with fertility issues.

Shutterstock

Katerina evoked the sense of intensity that characterises the early months of mothering, explaining it was both “the hardest thing” and “the most amazing thing” she has experienced. In fact, these extremes were linked in her interview, implying that the satisfaction and joy of mothering stem from mastering – or at least surviving – its difficulties.

After she decided to have a child on her own, Connie found motherhood much harder than anticipated. After what she describes as a couple of “breakdowns”, she was prescribed antidepressants. Connie’s depression stemmed from a disappointing birth experience, unsympathetic hospital staff while she was recovering, and inadequate support in looking after her new baby, manifesting in exhaustion and loneliness.

A more complex picture emerges

Across these 75 years there is a clear shift from the stoic and pragmatic accounts of postwar mothers to the more personal and expressive accounts of millennial mothers. There is also a rise in the number of women expressing difficulties adjusting to new motherhood.

Several factors explain these shifts. The rise of an expressive culture over the second half of the 20th century means more people feel comfortable sharing emotions. Linked to this, the popularisation of psychology has normalised mental illness (to some extent) and made it easier for mothers to admit emotional difficulties.

The dynamic nature of memory plays a role. For millennial mothers, memories of early motherhood are vivid and identity shifts easier to remember. For postwar mothers, memories of temporary difficulties have faded and any identity change has been integrated over decades.

But it’s also likely first-time motherhood was less of an identity shift for postwar mothers than today. Many grew up assuming motherhood would be central to adult identity; they didn’t view motherhood as optional. Since the women’s liberation movement, many Australian women have regarded their identity as closely linked to work, and motherhood disrupts that, at least temporarily.

A rising age of first motherhood contributes to this disruption. Postwar women were significantly younger when they became mothers – and it is very different for a 20-year-old to have a child compared with a 35- or 40-year-old, who may find motherhood more disruptive to her sense of self because her prematernal identity had become more solidified over time.

More and more women are choosing not to mother in the 21st century. I suspect one influence on women who decide against motherhood is because it looks inescapably and inevitably difficult. Yet motherhood itself is not the problem. It has the potential to be the most enriching experience of a woman’s life – but the preparation and support we provide to new mothers require dramatic improvement.

Motherhood comes with intense emotions, the likes of which a woman may never have previously experienced. This is hardly surprising if we keep in mind that two births are taking place: that of the infant and of the mother.

By improving our understanding of this profound transition we will also be able to better appreciate how mothers can be more effectively supported through one of the most cataclysmic – and rewarding – experiences of their lives: the maternal metamorphosis.![]()

Carla Pascoe Leahy, Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.