12 May Mothering, Smothering Or Othering?

Linda J. Graham writes about the displacement of parents, and particularly mothers, by ‘experts’ in modern life.

It goes almost without saying that the latter half of the 20th Century witnessed fundamental change to the institution of the family. While the emergence of feminism has received the majority of the blame, neoliberal individualism –bolstered by the discourse of ‘expertism’ – quietly festers at the root of the wound.

The shifting cultural and economic realities of modern life are seldom acknowledged for their tremendous influence; the problems they cause are too big, too hard, and too expensive to fix. In such a climate, parents become convenient political footballs.

Mothers, in particular, cannot seem to do anything right.

On the one hand, they are criticised for failing to nurture and spend time with their children and on the other, they are rebuked for new-age permissiveness or anxious ‘(s)mothering’.

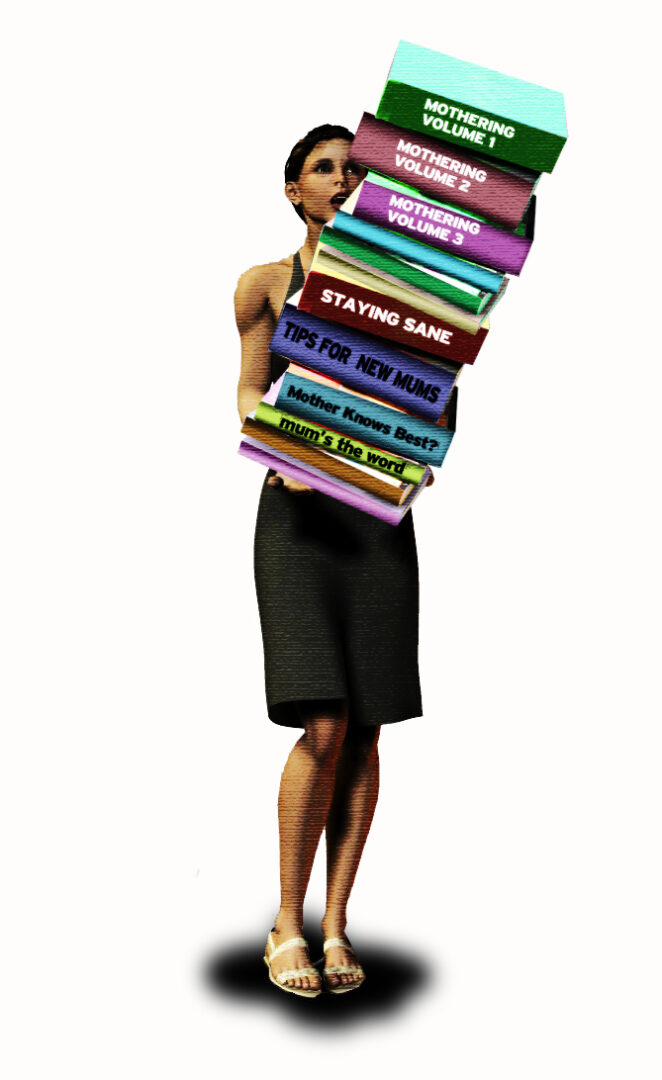

In Western cultures we have become divorced from the social and interrelational quality of child-rearing. In the absence of the extended family and communities based on kinship, new mothers find themselves alone with books, classes and any number of theories delivered by ‘experts’.

Pregnancy and birth have become medical procedures and the pregnant woman a mere receptacle of the as-yet-unborn citizen, replete with a regime of forbidden foods, beverages and other evil habits. For the unfortunate woman with deviant presentation or suspected cephalopelvic disproportion, there are CT scans and intensive intervention, and her desire for a more holistic experience elicits comments such as, “You should be grateful. If you were giving birth in the developing world, you would most likely rupture your uterus and both of you would die.”

New mothers can easily be overwhelmed.

In between breastfeeding and settling classes, the new mother is encouraged to map her baby’s progress against developmental norms. Hormonally charged new mothers are engaged by health professionals in conversations peppered with questions such as “Are you enjoying baby?” “Does your husband work long hours?” designed to carefully assess signs of postnatal depression.

Advice hotlines grant parents access to midwives who give advice on controlled crying, something that they never acknowledge is difficult to practise upon a child whom you love. I remember well the hardline advice of my sister– herself an early-childhood expert – in the early months of my daughter’s life, and my bemusement when she, 12 months later, could not bear to follow her own advice when it came to her child.

Advice hotlines grant parents access to midwives who give advice on controlled crying, something that they never acknowledge is difficult to practise upon a child whom you love. I remember well the hardline advice of my sister– herself an early-childhood expert – in the early months of my daughter’s life, and my bemusement when she, 12 months later, could not bear to follow her own advice when it came to her child.

The experts’ assault on motherhood has led to mothers no longer feeling that they can trust themselves, and intuition, ‘a mother’s knowing’, has been downgraded to the level of superstition and folklore.

Mothers who confess to emotional turmoil from sleep deprivation, mixed messages, insecurity and hormonal mayhem are referred to parenting centres or, in the case of a close friend, a psychiatric ward in the local hospital. Those who challenge or reject the advice of ‘experts’ run the gauntlet of social judgement. Seldom is it recognised in public discourse that one cannot follow all the advice one receives, nor accept every theory.

Theories of child-rearing clash with each other

Today’s mothers are caught in a double-bind: child-centred theories of child-rearing have bred both sentimentalism and essentialist ideals of the ‘good’ self-sacrificing mother, but these are ideals that clash with the dominant force of neoliberal individualism and the notion of the independent, entrepreneurial self.

Mothers who choose to stay at home with their children exist in a forgotten space, perceived as a voiceless, unproductive mass dependent on their husbands and/or the state.

Disapproval surrounds the mother of young children who works. This is tempered somewhat if the mother is seen as working to support the family: the mother who ‘has’ to work. The ‘careerist’ who chooses to work is especially demonised, characterised in popular discourse as selfish, lacking a ‘natural’ maternal drive and guilty of that cardinal sin: putting herself before her children.

Mothers are also judged through the successes and failures of their children. For example, findings that the majority of children have no vegetables or salad in their lunchboxes not only indicate that the root of the obesity problem lies with permissive, lazy (and probably distracted ‘working’) mothers but, such research works to justify the decontextualised advice of child-rearing ‘experts’.

These ‘experts’ are an ever-growing group of academics and media commentariat who provide convenient sound-bites during prime time on the sexualisation of ‘tweens’, the lack of morality displayed by teenage party-boys, and the ever-reliable ‘obesity epidemic’. Despite occasional references to consumerism, viral marketing and advertising designed to exploit ‘pester-power’, criticism and scrutiny eventually comes to rest upon the hapless modern parent and whatever they are doing wrong.

In response, self-appointed experts sweep in with parenting courses, ‘naughty circles’, family schedules, healthy-meal plans and exercise regimes that are ‘fun for the whole family’.

But wouldn’t we love to see what really goes on behind closed doors in the home of the expert? Will their children tell all, as did the famous Dr Spock’s, revealing to the world that, no matter how practised the parent, life and love aren’t perfect all of the time?

Can today’s parents resist the public administration of their parenting to re-stake their claim on the hearts and minds of their children, or has the discourse of ‘expertism’ so weakened the sovereignty of the parent that we no longer have any real authority or influence?

Children learn through what they see, but also through what they hear. Their own experience of childhood (and child-rearing) influences how they view the identity roles of mother and father, woman and man, feminine and masculine, female and male (typically cast in reverse order). But the home is no longer their only vantage point.

Somehow, lately, don’t ask me how, my daughter’s head has filled with dreams of marriage. I am baffled by this eight-year-old girl who pretends to receive text messages on my old mobile phone, engages in imaginary conversations with girlfriends about boyfriends and wonders aloud how many children she will have.

I am doing equally badly on the other side of the gender divide.

One Christmas Eve, my five-year-old son argued stridently as I was wrapping his father’s present that we couldn’t give Dad a “ladies’” present. I pointed to his Dad’s incredible output for the school cake stall, but still my son couldn’t accept our giving him a cookbook.

Where are my children learning this? Certainly not in the parallel universe they call home.

Feeling increasingly redundant, I lecture my daughter on finding herself before a husband, and worry when she seems to care more about physical appearance than moral substance. I hunt my son with kisses and hugs and have never contemplated telling him that ‘boys don’t cry’. Yet, I know deep down that soon I will be pushed away and the now barely there hints of masculinity will colonise his gentle boyish soul.

No matter what I do, my young daughter and son may still grow to believe that their parents are but strange aberrations, and that a woman should ‘naturally’ shoulder the burden of domestic labour, that her greater purpose in life is to bear and raise children and that the lion’s share of responsibility for doing this belongs to her.

They may grow to think their father ‘henpecked’ and choose partners and lives for themselves totally different from their old-age ‘new-age’ parents.

I wish my children a better future than that.

At times, I am at a loss to know what to do, but at those times – especially then – I remember to trust in myself and my motherly intuition. Believing that I know what to do when I don’t know what to do, simply because I know my children, helps me not only resist the public administration of my parenting by the experts, but also to refashion ideals of the perfect mother by writing for myself an alternative script.

Dr Linda Graham is an ‘expert’ in the medicalisation of childhood and other institutional responses to children and young people who are difficult to teach.

Illustrations by Harry Afentoglou