04 May Tashi Author Anna Fienberg Talks Children’s Books

The co-author of the Tashi books talks reading, writing and the far, far away…

Sunday mornings as a child in Australian author Anna Fienberg’s family were spent in bed, lost in magic spells, witches and dragons, and adventures between the pages of a book. Nothing’s changed – she still travels through imaginary worlds, only now she’s the writer as well as the reader.

She shares her world with us here.

On imagination

When I visit schools I tell stories…how a novel came to be written, the problem that triggered a story. Lately this involves my dog, the Indiscriminate Eater of beer cans, prescription glasses, CD cases, tissues, toilet rolls, cigarette butts, dental floss, my nightie, my son’s undies, desiccated frogs.

After the story, I ask the children ‘What kind of dog did you see in your mind?’ and Labradors abound, collies, dream dogs and sometimes, bears. I congratulate the children for their hard work, noting that their busy minds were meeting mine.

‘It’s a marvellous magic trick you perform,’ I say, ‘making up pictures to go with the story.’

We’re born with it, this ability to imagine what isn’t there. It’s our secret self, invisible but essential for life. Like the shape of our hearts, no two imaginations are exactly alike. Alan Finkel, our chief scientist, advises us to read science fiction in order to prepare for the future. And yet often the imagination is dismissed as child’s play, as if the doing of things in the ‘real’ world is all that matters.

We know that to make a choice, to commit to something, we have to imagine our way into it first. We try to see consequences before we act, rehearse various scenarios. When children asked Kim Gamble, the illustrator of Tashi, how he could draw ‘like magic’, he told them he had to imagine a scene first, and then he just copied it down.

Conditions of chronic deprivation can make our imagination wither and shrink. But some conditions can make the imagination bloom – and chronic exposure to good fiction is the best one I know.

On reading

A story is a lesson in empathy – words come alive inside us as we slip imaginatively into a character’s shoes, much as we do in conversation with a friend.

But in books we can meet people with experiences completely foreign to our own.

We lend them our feelings – they seep in like watercolours, bringing colour and meaning to the tale. With each book, our imaginations are exercised, much like a gym workout increases our fitness.

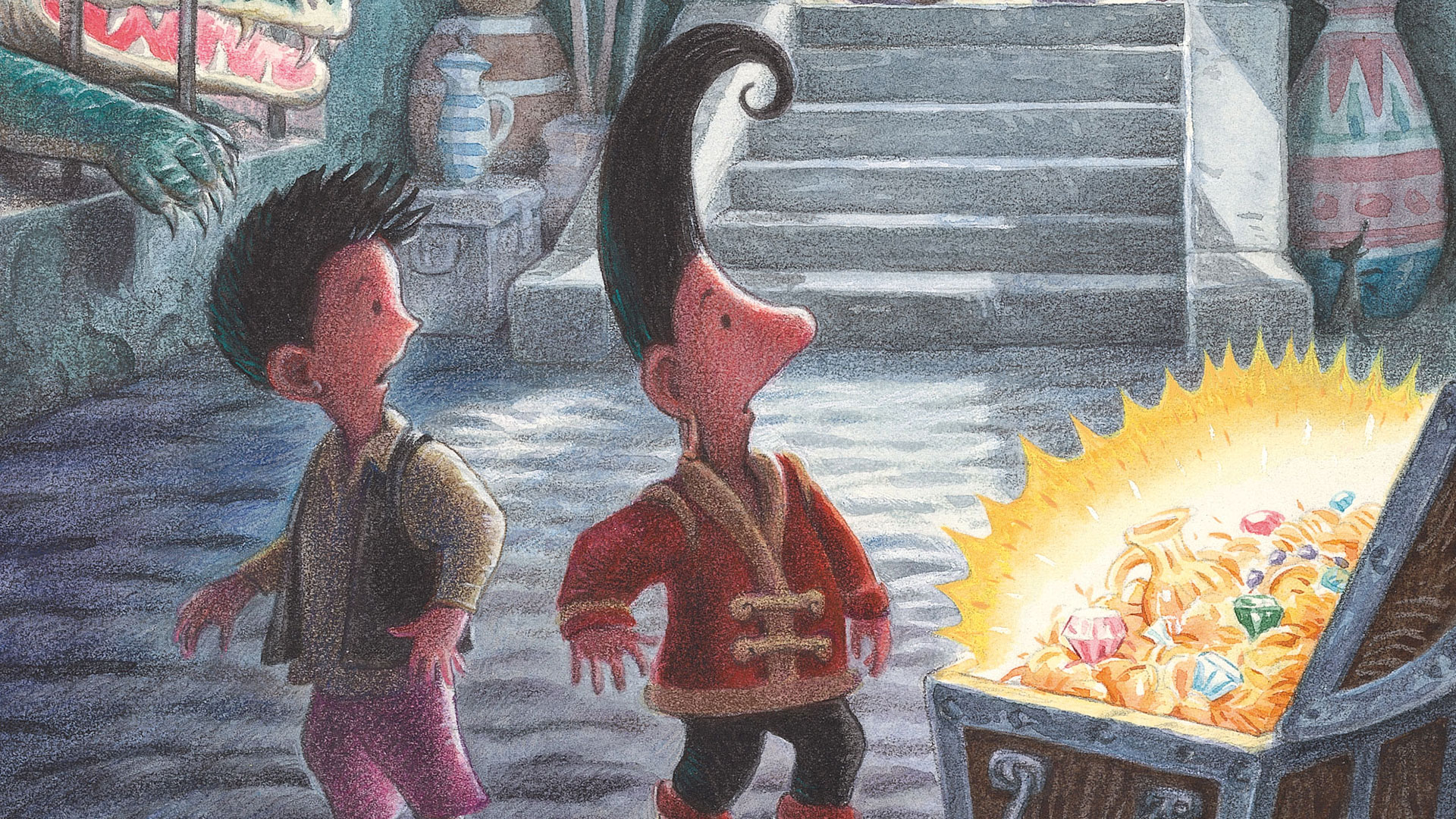

Fiction shows us that anything is possible, and solutions to the most dire problems come from imagining our way out. I think that’s why children like the character of Tashi, the boy who wields his imagination – that place where ideas come from – to defeat greedy giants and ravenous dragons.

A child told me once that she took Tashi with her everywhere because you never knew when a problem might spring up, and Tashi would know how to solve it. I could see she felt just like I had with Anne of Green Gables, the first person who told me I wasn’t as weird as I thought, that I had company, and wasn’t alone in my own mind.

Perhaps this is one of the greatest gifts of story – we get to know intimately the secret selves of others. And there, so often, we meet ourselves.

On reading at bedtime

Reading stories to my son when he was born was just about the only thing I knew how to do. And not only at bedtime. I found it to be one of the greatest comforts, for both him and me.

And so easy! Even when you’re exhausted, the words are there – you don’t have to struggle to find them, you can just use those of the author, who has spent months or years trying to choose just the right ones.

You get to snuggle close, interrupt the story to compare experiences, point at pictures, ask about feelings, discuss all the most important and intimate aspects of being alive and part of the human race.

Or you can just be silently awed together, your hearts pounding as you lift off to the far away place.

Oh it’s delicious, except when you have a frightening dinner party to cook for, or you have to go to work.

I wasn’t conscious of this when I wrote Tashi, but now I think I’m aware of how much children love the entrance of their parents into this imaginative game, when the parent or close adult can hold that world with them, seeing it just as real and enthralling, as they do.

In my childhood, stories were as regular as lunch, whether it was a tale about the stray dog at the shops or a new book. My mother, Barbara, who co-wrote Tashi with me, was a fabulous storyteller. She happened to be Teacher Librarian at my own primary school, but when she began the best part of the lesson, the long luxurious read aloud, she transformed into a being from somewhere else. I forgot who she was and the carpet beneath me, and like everyone else, I never wanted the story to end.

On writing for children

Childhood experiences are written with indelible ink – maybe it’s the firsts in every one of those that makes them so powerful. The poet Louise Gluck wrote: We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.

I think I write for children in the desire to create another world to live in.

A world where characters are beset with troubles and discover a myriad of possibilities for dealing with them. I want to live with adventure and hope and good company for my own inner child as well as that of my readers. Writing for children provides many thrills but sometimes you have to keep the light on in the hallway, and hug your pillow to your chest all through the night.

On helping children to love writing

When we encourage children to tell or write their own stories, we are honouring their imaginations. Get a notebook, I tell older children, you don’t have to show anyone, it’s all yours, write down your dreams, what you remember about being five, moving house, being scared, what your best friend said.

Learning to put your inner world into words is perhaps one of the most useful tools in living a good life.

If a child wants to write a story but says ‘nothing ever happens to me’ or ‘I don’t’ have any ideas’, throw some myths and fairy tales at them. Fill the house with Odysseus strapped to the mast as he sails past murderous mermaids, watch King Midas turn everything to gold – even his own son!

With Tashi, Barbara and I took fairy tale characters from both our childhoods and tweaked them, adding a pinch of loneliness or vanity, bad housekeeping or kleptomania…The classics can trigger a world of invention – and the characters are long out of copyright!

On reading in times of trouble

Even in our worst times, fiction helps. Grief can drag you off to an island, making you feel separate from the human race.

But books faithfully follow. Infinitely patient, they quietly take your hand, winging you out of your life and back in, solaced, expanded, with new understanding.

‘When I read,’ a Year 6 boy told me, ‘I feel bigger than I really am.’

I think children’s books are so important because this is where it begins – learning what book is right for you, at a particular time, is like learning what person is right for you.

Through fiction a child learns the terrain of her own inner world and others’ – that most mysterious of places that can, in real life, seem forever out of reach.

Anna Fienberg has written over 40 books for children and young adults, including The Magnificent Nose and Other Marvels (winner of the Children’s Book Council of Australia Book of the Year). Her latest book is Monsters (Allen & Unwin, $24.99), a picture book illustrated by Tashi illustrator Kim Gamble and Stephen Axelsen. For activity sheets and more about Tashi, including a video of Kim drawing him, go to tashibooks.com.

Think you could write a children’s book? Anna is conducting a ‘Writing for Children’ course for beginners over four Thursday nights from 14 June at the Faber Writing Academy in Sydney. Bring your imagination! For more writing courses, inspo and chats with mums who write, see our story Pen To Paper: Do You Have A Book In You?

Illustration by Kim Gamble.