15 Mar Why all young people should get the HPV vaccine – girls and boys

Cancers caused by the human papillomavirus or HPV are entirely preventable. And now it takes just one dose to vaccinate against it, write Julia Brotherton, Claire Nightingale and Claire Vajdic

Cervical cancer is a devastating disease that can strike down women in the prime of their lives.

Amazingly, this disease is now almost entirely preventable through vaccination and screening. But this success means that every case that does happen represents a failure to provide and make accessible (and acceptable) the prevention programs that we know work.

It’s a failure of political will, of government, and of society’s commitment to the rights of girls and women and people with a cervix.

So, why is this still happening?

Just a single vaccination

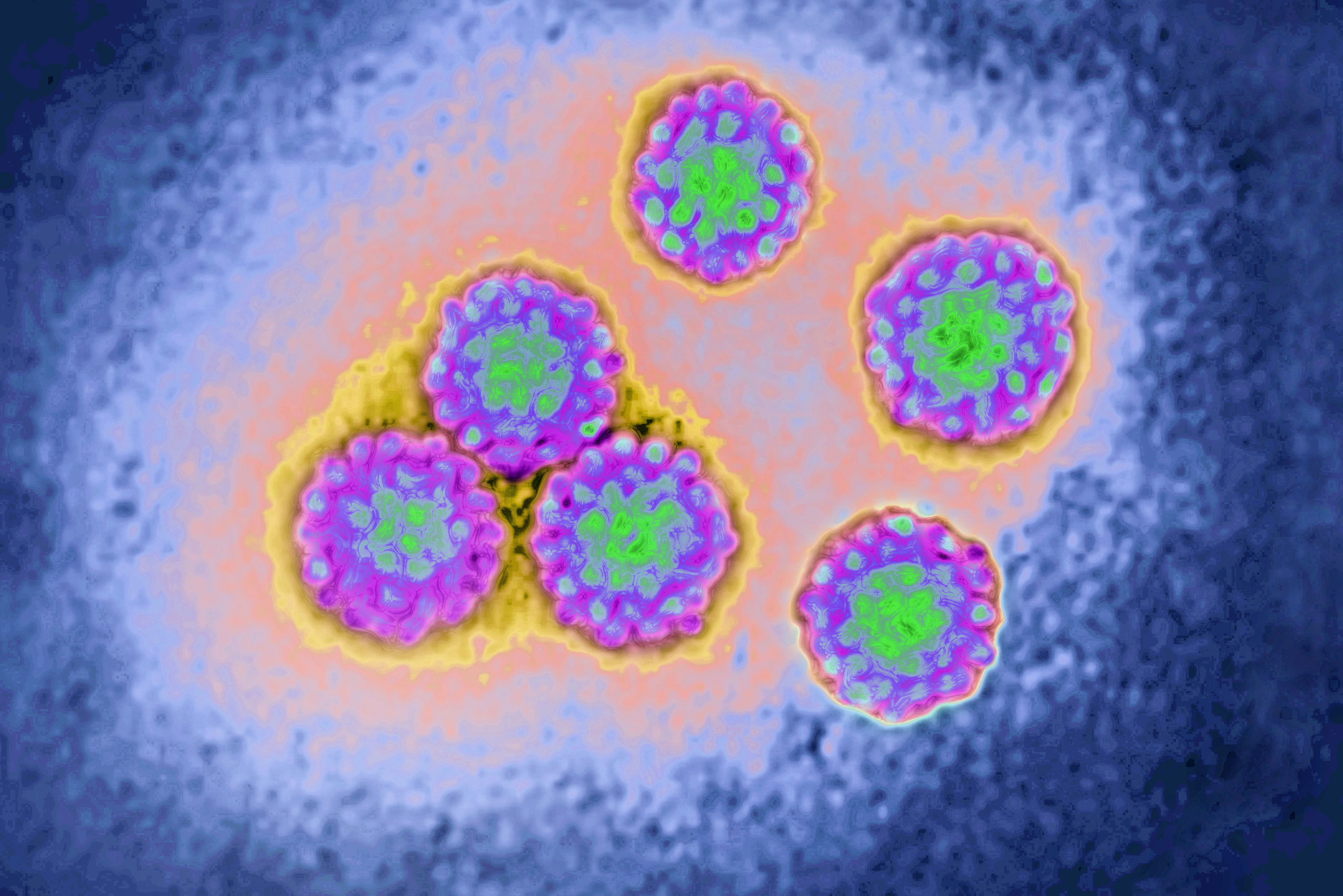

Cervical cancer (cancer of the neck of the womb) is almost always caused by long-term infection with certain types of human papillomavirus, commonly known as HPV.

Infection with HPV is incredibly common – it’s nearly universal – and has been called ‘the common cold of sexually transmitted infections’.

In fact, it’s estimated that around 80 to 90 per cent of us will have at least one HPV infection in our lifetimes.

Fortunately, in most cases, infection has no symptoms (although it’s worth noting some low-risk HPV types can cause genital warts) and is controlled by the immune system without us ever knowing we had it.

But there are 12 types of HPV that are high risk. It’s only when someone is infected with these HPV types and infection remains uncontrolled for a long time that cancer can eventually result.

We now have remarkable vaccines developed in Australia that prevent HPV from entering our cells and causing infection in the first place.

These vaccines are nearly 100 per cent effective if they’re given prior to exposure to the HPV types they cover. And this is why the World Health Organization recommends them as a routine vaccination for girls aged between nine and 14 around the world.

Vaccinating this age group means it’s done before the age at which most people become sexually active – which is when they are likely to encounter HPV for the first time.

Research in multiple countries has now shown that these vaccines do indeed prevent cervical cancer in the population when given routinely.

They are also very safe. These vaccines have been closely monitored in routine use for almost 20 years, in which time more than 500 million doses have been given around the world.

The latest evidence has also shown that just a single dose of HPV vaccine is effective and already 45 per cent of countries have moved to one dose from the previously recommended two doses.

This is very exciting. It means that the vaccine supply can reach more people while making administration easier and it costs less for countries to vaccinate.

Easier testing at home

Meanwhile a similar technological revolution has taken place in cervical screening.

Gone is the Pap smear, which required sampling of the cells from the cervix by a doctor or nurse, staining them and reading of the slide in the laboratory to find any abnormal cells.

While Pap smears were effective at preventing cervical cancer, they required very frequent screening (every two years in Australia) because they were not always able to find cell changes.

These days, cervical screening programs use a molecular test that looks for DNA from the 12 HPV types, called HPV-based screening.

It’s a lot more sensitive than Pap smears because only those people who have HPV detected then need to be examined and people with no HPV found do not need to screen again for five years.

If HPV is present in the cervix, its DNA will be shed down into the vagina making HPV-based screening just as accurate using a sample from the vagina as it is from the cervix.

This means many people can take their own sample using a simple swab from the low to mid-vagina.

This self-sampling method (often called self-collection) not only makes cervical screening easier, but also more accessible to people who may have barriers or issues that make traditional, more invasive cervical screening collection harder for them.

This could include a history of sexual trauma, a previous negative experience, fear, anxiety or lack of access to a female provider.

The tools we have to prevent cervical cancer are now so effective that the World Health Organization has urged all countries to work towards the global elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem.

The ambition is that within the next 100 years cervical cancer becomes a very rare disease in every country.

Prioritising the health of women and girls

Our team recently reviewed how socioeconomic status (or the resources available to people in their lives like education and income) influences the occurrence of cervical cancer as well as access to HPV vaccination, cervical screening and treatment.

We found that there is still a long way to go.

A country’s wealth is a direct predictor of the rate of cervical cancer – poorer countries having much higher rates.

We also found that there is a strong link between socioeconomic status and the likelihood of HPV vaccination, screening and getting treatment, both at an individual and societal level.

So, what can we do about this unfair access to cancer prevention for women?

Globally, governments need to prioritise the health of girls and women, making a firm commitment to ending cervical cancer. We need systems in place to ensure everyone with a cervix can access HPV vaccine, cervical screening and cancer treatment.

This will benefit wider society by increasing the accessibility of health care, ensuring it is free and all about the person, scaling up community-based health care systems, increasing vaccine confidence and developing infrastructure for cancer treatment and palliative care.

We must ensure equal, culturally safe access to vaccines, screening and treatment in Australia for everyone including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other priority populations.

Doing your bit

You can also help. Are you and the people you love protected against cervical cancer and other HPV-related cancers?

In Australia, boys and girls can get vaccinated.

For males, this not only protects any future partners from HPV and cervical cancer, but can also provide direct protection against other HPV-related cancers including anal cancer and cancers of the oropharynx (throat), which has seen a recent steep increase.

If HPV vaccine was missed at school, young people can get a free catch-up vaccine before age 26 at your GP, community health centre, Aboriginal Medical Service or pharmacy (and remember you now only need one dose).

Let your mum, sisters and aunties know they can now do their cervical screening with a self-sample (easy, quick and just as accurate) if they prefer and talk to their trusted health care provider.

Learn the possible symptoms of cervical cancer (like bleeding after sex, irregular bleeding or post-menopausal bleeding, or pelvic pain) and see your doctor if you have any concerns.

Yearly in March on International Women’s Day, let’s celebrate the strength of women and champion a world where women’s equal right to health and wellbeing is a given. Together, we can eliminate cervical cancer.

If you’re in Australia and want to know more, you can visit the Cancer Council Australia’s HPV vaccination website, find more resources at the National Cervical Screening Program and access your screening history through MyGov and the National Cancer Screening Register.

Professor Julia Brotherton, Professorial Fellow, Cancer Prevention Policy, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, Univeristy of Melbourne

Associate Professor Claire Nightingale, Principal Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne

Professor Claire Vajdic, Professor, Integrated Data for Health Equity Group Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales