28 Mar Tales Of Our Times

John W. Luton delights in the rewards of encouraging children to write about their holidays and other special experiences.

My wife, Cheryl, and I have always encouraged our children (and our students) to write about their holiday activities, as a means both of preserving memories and of using the process of writing to promote creative narration.

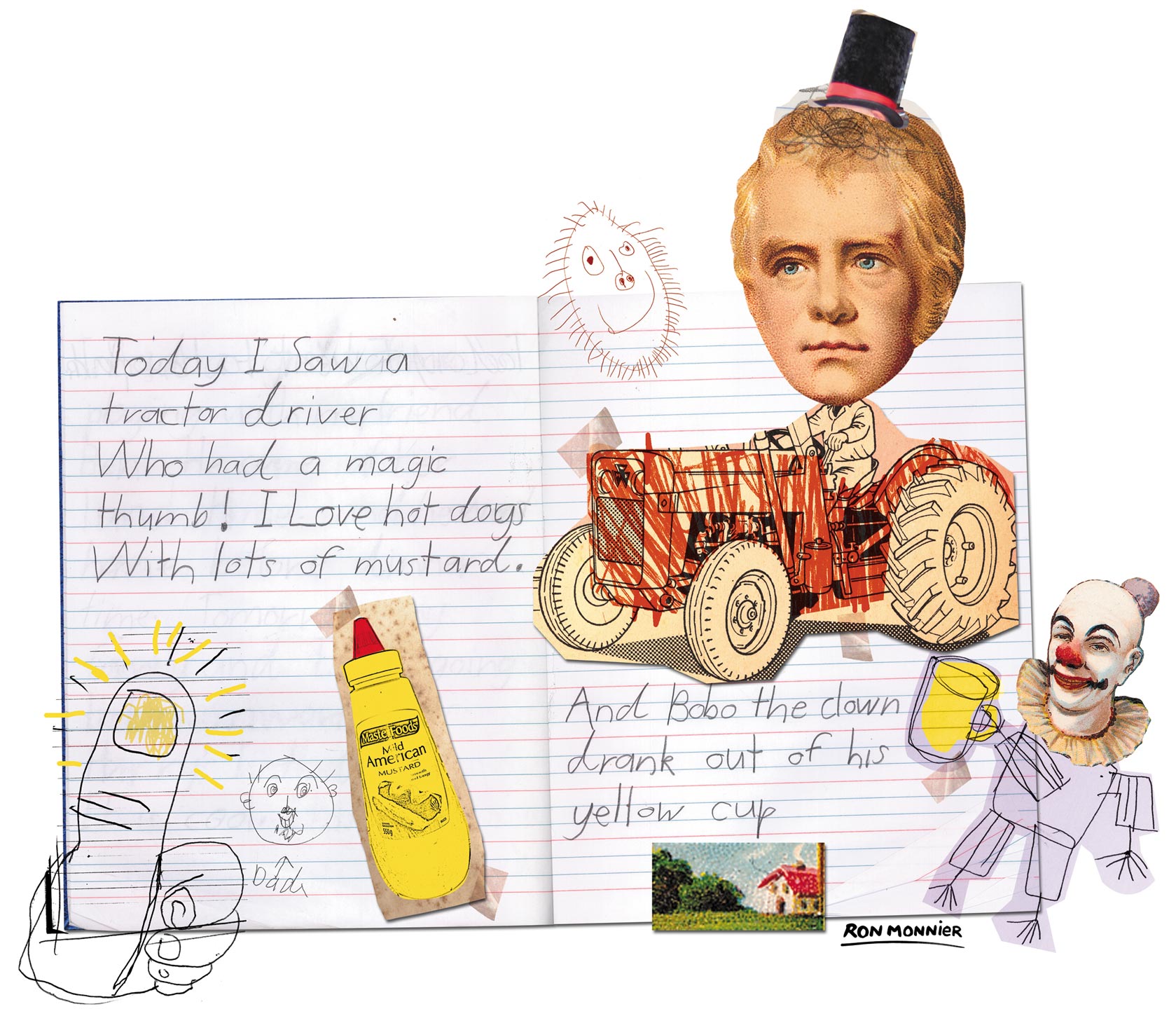

Cheryl has also employed this technique with our six-year-old step-grandson, Seth. While he is still somewhat limited in his ability to write out his own narration, he is quite capable of expressing himself imaginatively while Grandma constructs the more permanent record. And in addition to dictating the majority of the narrative content, Seth also often supplies his own illustrations.

Over the past couple of years, their collaboration has produced a diary of what we’ve come to call ‘creative chronicling’. We hope that this will encourage a lifetime of imaginative narration in Seth.

The capacity and the need to tell stories seem always to have been among the distinguishing marks of humankind. From time immemorial, we humans have gathered in family circles and narrated events and experiences that have registered meaningful impacts upon our lives.

While children have always been readily engaged by a good story – especially when expressed through the words and antics of a skilled raconteur – their abilities and desires to craft their own narratives have, perhaps, remained less recognised and largely unexplored. Whereas adults are sometimes reticent to allow their creative energies free rein, children feel no such compulsion to be bound by societal conventions.

In other words, while adults are keen to include all the necessary narrative components, such as beginnings, middles, and endings – complete with development of characters and plot points interspersed along the way – children are far less anxious about such trivial things.

Casting aside the as yet unknown rules of noun-verb agreement, and making no attempt to eliminate the passive voice, children can allow their narrative expression an unfettered odyssey of the mind. Add to the mixture a complete disregard for correct spelling, and you have the perfect recipe for a story that at once records and enhances a child’s lived experience. The narrative can then be assembled according to a more whimsical structure, which exists only to spark and then fan into flame the young author’s creative imagination. This description encompasses both the aim and the method of our approach to creative chronicling.

When Seth was four years old, Cheryl and I agreed to have him stay for the weekend while his parents embarked upon a short getaway to celebrate their recent wedding. We decided to use this time alone with Seth as a chance to get to know our new step-grandson a little better.

Two major events were planned for the weekend: a trip to a nearby plant nursery to attend a show starring a variety of farm animals, and an evening at a major entertainment venue where Seth would encounter many of his favourite characters from the world of cartoons and film.

These back-to-back outings were planned several days in advance to generate as much excitement as possible. The advance planning also helped to allay any anxiety that might result from Seth being separated from his mum for the weekend. While he had already spent the night at our home on a couple of occasions, his mum had never been more than a few kilometres away and had always been easily accessible by telephone. This time, however, we wanted at least to reduce the need to phone Mum and Dad – a plan that the honeymooners heartily endorsed.

When Cheryl told me of her plan to use the weekend as an opportunity to introduce Seth to the process of creative chronicling, my own excitement began to build.

Seth’s first attempt at narrative dictation produced a document that ultimately transcended the boundaries of the experiences he recorded.

Perhaps the most serendipitous aspect of the exercise has been the opportunity for him to revisit these experiences – now some two years past – and see his reactions to the words he originally dictated to his grandma.

Now that he has been at school for a couple of years, he can actually read the words of the narrative himself. While some of the memories recorded in the piece have already begun to dim, others seem to be reinforced by the narrative’s content.

For example, when Seth first read the part of his narrative about a tractor driver whose thumb magically lit up, he said, “Oh, I had forgotten all about that!” And while he remembered eating hotdogs for lunch that day, he could not believe he had eaten mustard, a condiment he now detests.

When he read about the bright yellow cups, his eyes danced as he remembered them vividly. He also had amazing recall of some of the cartoon characters he had encountered – probably much more than he would have had if he and Grandma had not taken a few moments to record the events in their journal.

Creative chronicling can help preserve the memories of childhood, not only for the child, but for parents and grandparents as well. As I think back on how this recorded narrative has enriched the experience of everyone involved, I am thankful that we recorded these events in a way that will enable us to relive them time and again. My wife and I have often used the creative-chronicling tool to enhance daily experiences and deepen family relationships, and the dividends received from doing so far surpass the requisite investments of time and patience.