09 May Why a child-centred focus in response to domestic violence is long overdue

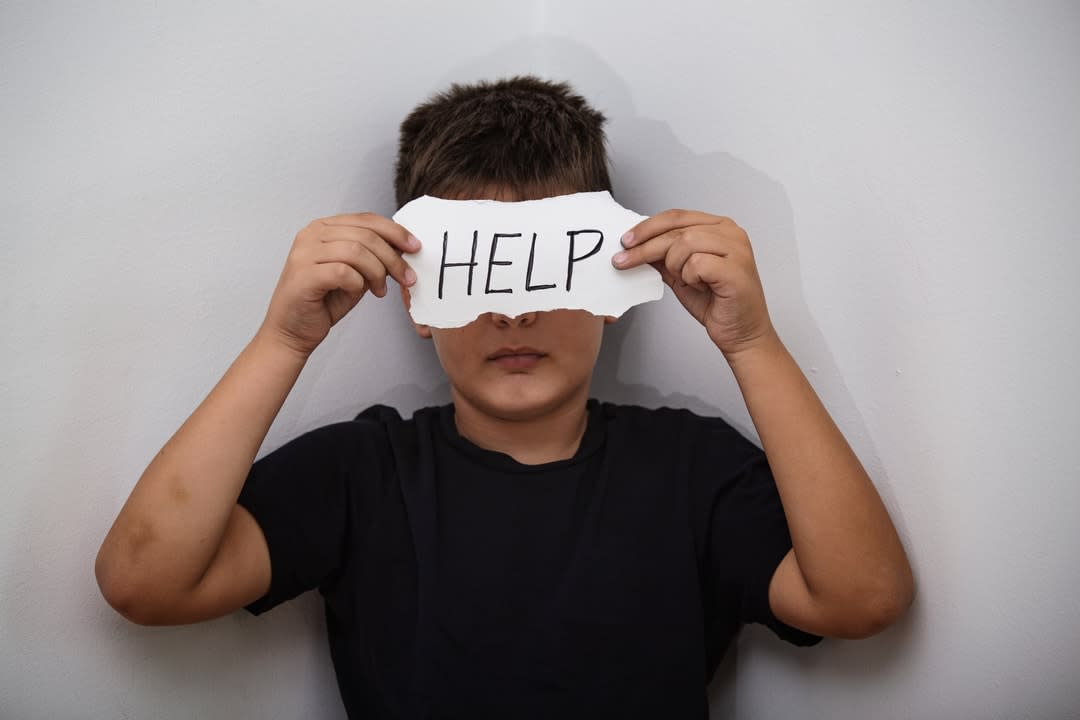

Why we need to focus more on the needs of children in domestic and family violence responses, writes Silke Meyer

In 2015, domestic and family violence (DFV) was declared a “national emergency” in Australia, with its impact on women and children costing the country an estimated A$22 billion each year.

In 2019, the short and long-term consequences of childhood trauma, including DFV, were estimated to cost the Australian economy A$34 billion each year.

While children may witness and experience parental DFV in many ways, extensive research evidence generated over the past two decades clearly identifies childhood exposure to DFV as a predictor of adverse social, emotional and behavioural outcomes for children and adolescents.

Children exposed to DFV have been found to experience increased levels of behavioural problems, depression and anxiety, which may result in withdrawal from peers, school and family and/or expressing themselves through anger and aggression. In some cases, this behaviour may continue into adulthood, maintaining the cycles of violence established by abusive parents.

While policy and legislation increasingly recognise these detrimental effects on children, they frequently remain invisible in the wider discourse around DFV. Most interventions remain parent rather than child-centred.

Responses have persistently focused on removing the abusive parent from the home (for example, through arrest, incarceration or exclusion orders), placing mothers and children into crisis accommodation, or removing children from both parents where substantial child welfare concerns arise.

All these current responses treat children and their support needs as an extension of the safety and support needs of the adult victim/survivor of DFV. While they aim to put a halt to children’s exposure to DFV due to the known adverse and often lasting effects on children’s safety, development and long-term well-being, these responses don’t recognise the importance of ongoing, child-centred recovery needs.

The well-established intergenerational impact of DFV, along with other adverse outcomes for children, suggests that children’s support and recovery needs are not addressed by default when addressing the support needs of mothers as victims/survivors or holding perpetrators accountable in their role as fathers. Instead, it suggests that it’s time we start treating children as victims in their own right and address their need for recovery from DFV-related trauma accordingly.

The invisibility of children

The invisibility of children remains a significant shortcoming across recent policy efforts. Most recent national parliamentary inquiries, along with the recent call for submissions by the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, place women as victim-survivors at the centre of each inquiry. Children may be mentioned in the context of reducing violence against women and children (for example, the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and Children). However, recent policy, legislation and intervention-related calls for information remain centred on adult victims and their support needs.

Since the onset of the pandemic, research and advocacy have increasingly focused on the effects of the pandemic on women’s experiences of DFV, including its increase in prevalence and severity. Global data predicted early on that for every three months the lockdowns continue, an additional 15 million cases of DV will occur. Recent Australian data has confirmed the feared increase in the prevalence and severity of DFV.

While the United Nations and specialist children’s services have raised concerns early on that children may be the biggest victims of the COVID-19 pandemic due to their exacerbated vulnerability and invisibility, the discourse around DFV has remained adult-focused. Yet, children’s exposure to parental DFV will likely have increased at similar rates to those of adult victims.

If children continue to remain invisible in the discourse around COVID-19 and DFV-related support and recovery needs, Australia will see long-term effects on children that will likely exceed documented adverse effects in intensity and longevity.

Further, ongoing school closures and household isolation rendered risk to children increasingly invisible. For many children affected by DFV, school attendance offers a break from the unsafe family home environment and an opportunity for external support persons to identify, report and monitor risk. With schools and many childcare centres having mostly been closed since March 2020 in Victoria, for example, only children already identified as vulnerable and at risk (such as those with past histories of child protection involvement) have had access to on-site supervision. The vast majority of children affected by DFV will have been isolated from educators, extended family and any other trusted persons outside of the family home.

Placing children at the centre of DFV and COVID-related recovery

With a slowly-emerging focus on the long-term effects of the pandemic on community, household and individual well-being, especially in states as heavily affected by strict and prolonged lockdowns as Victoria, it’s critical to include the support needs of children affected by DFV on the COVID-19 recovery agenda.

While a child-centred focus in responses to DFV is long overdue, given the well-established long-term effects on many children affected by DFV-related childhood trauma, it’s particularly time-critical in the wake of COVID-19.

If children continue to remain invisible in the discourse around COVID-19 and DFV-related support and recovery needs, Australia will see long-term effects on children that will likely exceed documented adverse effects in intensity and longevity.

Therefore, it’s critical for state and federal governments to identify and address the nature and extent of children’s support needs in the wake of the current pandemic through child-centred recovery support. Investing in child-centred support constitutes an investment in long-term child well-being, thus generating significant economic, social, and cultural benefits.

Here, listening to the voices of young people with lived experience will be critical. If we’re serious about improving the outcomes for children growing up with DFV, we need to start acknowledging children as victims in their own right and as experts in their lived experiences.

Silke Meyer was the Deputy Director, Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Associate Professor (Research), Criminology at Monash University at the time of writing this article.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article