23 Jan Bittersweet Reflections

Cate Macinnis-Ng reflects on the brief life of her first child as she contemplates the birth of her second.

The responses we’ve received to “We’re pregnant again” have ranged from a gushing, “Oh that’s so fabulous, how wonderful!” to “Don’t eat sushi or brie”. I translate these responses to mean, ‘Well, you can move on and get better now. This will cure you’, and ‘You can prevent what happened before’. The truth is, there is no cure for our pain, and we had no control over Callum’s condition. The implied meanings of the responses of well-meaning friends and relatives only trivialise our grief and isolate us in our sadness.

Callum was born with a blood disorder called Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (WAS), unique to boys. It’s so rare that we didn’t find out he had it until he was nine months old. What seemed to be a case of severe eczema turned out to be much more serious. Constant trips to the paediatrician, following strict diets and cream-application procedures provided only minimal relief from red, itchy skin that was constantly infected.

In desperation, we took Callum to the children’s hospital, where he had his first blood test. Wet dressings provided relief for Callum’s sore skin and the next morning we saw the dermatologist, who was the first to give us some answers. Callum had very low levels of platelets in his blood and this was why he had always bruised very easily. We were referred to the haematology team and quickly found out the three main symptoms of WAS: immune deficiency, thrombocytopenia (low platelets) and severe eczema.

I remember reading on the internet the line, “Most boys with WAS die before their second birthday”. I felt my blood stop in my veins. My heart dropped, but there were no tears or disbelief, just determination to do what was necessary. Statistically, one in every 250,000 boys has WAS. There is perhaps one child with the disorder born in Australia every one to two years. My mind could not compute such information. Ironically, it was eczema, the least life-threatening of the three symptoms, that was the most distressing for Callum, and we worked hard to keep it under control. He also needed a bone-marrow transplant, but the fact that there was a treatment gave us hope.

The months that followed passed in a blur of hospital visits and constant treatments, mixed with special times and happy memories. Callum brought joy and excitement to our lives. Despite his discomfort, he was a delightful boy with an easy smile. He loved nothing more than to see other people happy. His first birthday was a big event with extended family. He knew there was something special going on and that he was the centre of attention. He was adventurous and curious about the world, and simple activities were a source of wonder and pleasure to him. A trip to the park or a walk on the beach or in the rainforest were his favourite activities. We made the most of weekends, ‘family time’, taking Callum to the zoo, the park and the beach.

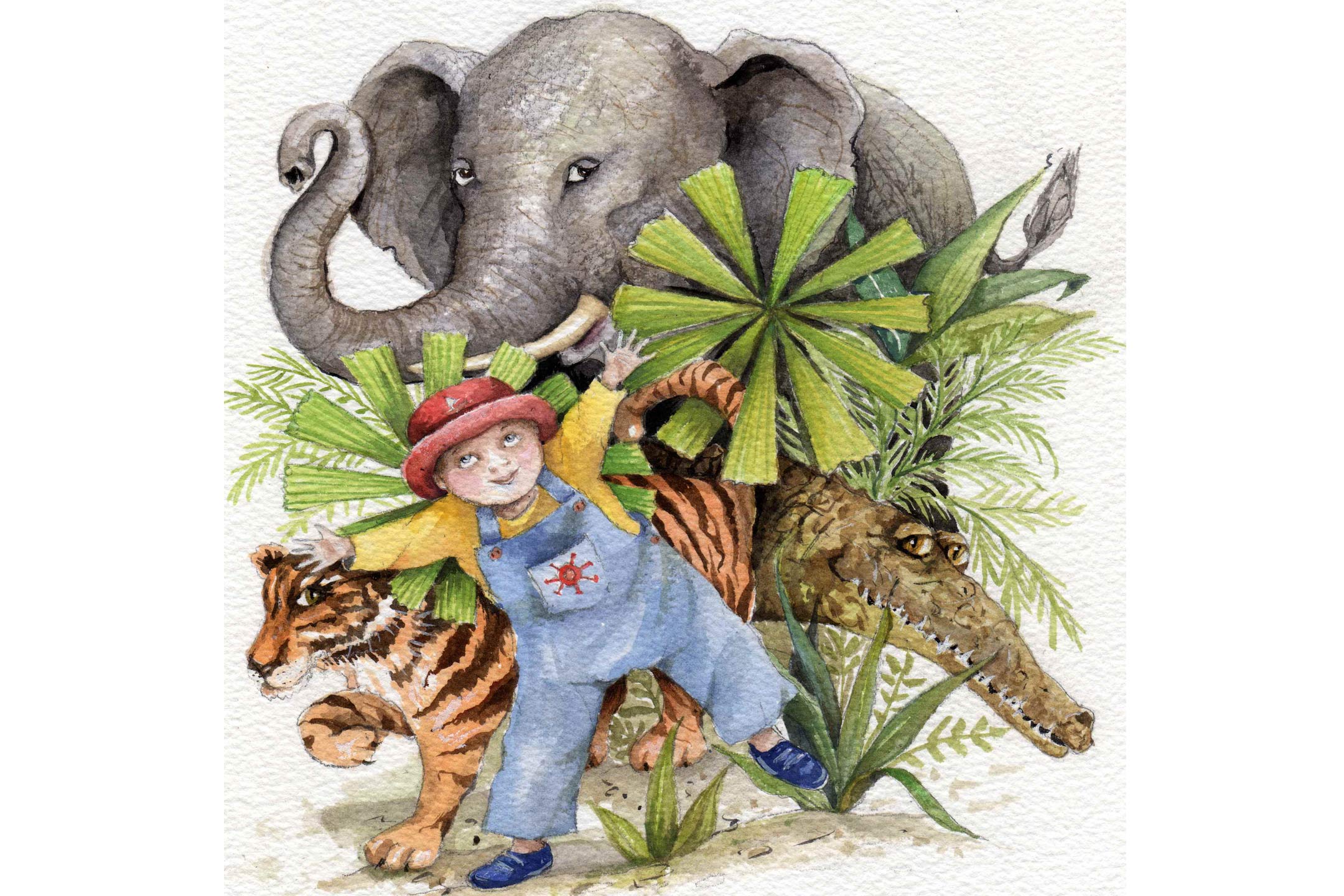

With the date of the transplant approaching, we took Callum to Noosa and spent five glorious days playing together, just the three of us. One morning we made the trip to Australia Zoo and Callum spent the day snorting for the pigs, baaing for the sheep, trumpeting for the elephants and growling for the tigers and crocodiles. While we waited to catch the coach back to Noosa, we looked at the animals in the gift shop. Callum showed no interest… until he saw a particular stuffed tiger. ‘Tiger’ was specially chosen for his soft fur and warm colours and became his constant companion, a comfort both to Callum and to me.

Callum did not make it to the transplant. He simply ran out of platelets. There were signs that things weren’t right, but there was nothing that could be done. A spontaneous bleed into his brain crushed his brainstem, and our smiling, dancing boy, who’d watched The Wiggles on Dadda’s lap the night before, became still. He was just 16 months old.

Callum did not make it to the transplant. He simply ran out of platelets. There were signs that things weren’t right, but there was nothing that could be done. A spontaneous bleed into his brain crushed his brainstem, and our smiling, dancing boy, who’d watched The Wiggles on Dadda’s lap the night before, became still. He was just 16 months old.

Nine months later, it still doesn’t seem possible. How did it go so wrong? We did everything we could. We were like a well-oiled machine, my husband and I – we knew what we had to do and we were willing to face anything for Callum, yet somehow that wasn’t enough. We’ve searched our memories for something we could have done differently, discussed the possibilities that were open to us at pivotal points. But it seems that Callum lived the life he was meant to have.

We cherish the memories of the things that made Callum unique. The way he stroked my hair when he was in his papoose, his excitement about seeing his Dadda at the end of the day and the way he expressed it by waving his arms. His habit of reading animal books and making all the sounds as he read, and his love of waving to strangers in the street. His crazy splashing in the bath, and his patience while we applied his dressings and administered his medicine. His love of Dr. Seuss’s ABC and passion for The Wiggles. His touch and smell and his special cuddles for us and for Tiger.

Those memories leave us with so many questions. Will our new child be like Callum? If he or she has similar traits, will that remind us of Callum too much and make us sad, or will we be sad if there is not enough of Callum in his younger sibling? Will I be able to overcome my fear of loving another child?

One thing is certain: the chances of our new child having WAS are very low because I am not carrying the X-linked gene change. That is a huge relief, but our awareness of other diseases and conditions through spending time at the hospital tempers our optimism. We are hopeful for the future, and Callum’s zest for life inspires us.

Being parents without a child has been one of the most difficult things for us, but having another child will not reduce the way we love and miss our firstborn son. I have come to see that happiness and sadness are not mutually exclusive. While I feel as though the pure joy I felt during Callum’s life can never be recaptured, I know that his younger sibling, whom we have affectionately nicknamed ‘Tiger’, will bring a different type of contentment.

It’s the friends and family who understand that happiness and sadness can go together who have been the most supportive since Callum’s death. They understand that the arrival of a second child after the loss of the first is emotionally complicated. They convey this, not by what they say, but by the pause, the look in their eyes, or the wordless hugs that they gave us when we told them we were expecting. Sometimes it’s what is left unsaid that is most comforting.

Illustrations by Penny Lovelock