12 Apr Book review: Can your mental health impact your pregnancy?

Camilla Nelson How one woman’s traumatic experience drove her investigation into pregnancy and mental health

Years ago, a friend told me how, a week or two after giving birth, she had been gripped by the idea that her baby had been abducted by aliens. Hearing this, I was astonished. My friend was a smart, well-grounded, rational woman – a medical doctor, in fact. And ideas about the mental health impacts of pregnancy were new to me.

I was, at that time, pregnant with my first child and had become anxious. I was not myself. My friend wanted to let me know that I wasn’t a freak, that pregnancy was tough and complicated and, maybe, things could be worse.

Postnatal psychosis – including mania, hallucinations and delusions – is a serious mental illness that can develop in mothers soon after giving birth. It is reasonably rare, affecting one or two in every 1,000 women who have a baby. Most women recover completely, as my friend quickly did.

But anxiety during and after pregnancy is common. It affects as many as 30% of pregnant women in Australia. Of these, one in five women will be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.

And yet, nobody talks about it.

In The Cost of Labour, Natalie Kon-yu investigates women’s mental well-being in pregnancy with rare honesty. Kon-yu knew she was seriously unwell when, at eight weeks, her legs began trembling uncontrollably. She was already nauseous and unable to sleep. A locum prescribed Valium. But she kept waking in the dead of night with shaking legs. “It’s hard to write about this time, even eight years later,” Kon-yu says.

I grew increasingly anxious and oscillated between thinking that the tremble in my legs was caused by the pregnancy and worrying that it was caused by something that could potentially harm the pregnancy.

‘List the colours of the rainbow’

Kon-yu went to her local doctor for help. The GP told her to try listing the colours of the rainbow. “I stared at her,” Kon-yu writes. “I couldn’t believe that she couldn’t see the state I was in.”

Next visit, Kon-yu brought a friend to better explain her situation. This time the GP brought in a senior doctor who – addressing Kon-yu’s friend, and not Kon-yu – advised immediate hospitalisation because “I had expressed a desire to harm my unborn child”. Her friend exploded. But Kon-yu couldn’t say a word: “I sat there, small and ashamed, unable to speak for myself.”

Author provided

Kon-yu tried a different doctor who, hearing she had been taken off Endep – a commonly prescribed back-pain medication that influences mood, but is contraindicated in pregnancy – prescribed SSRIs. He mentioned this new medication could make her anxiety worse before it got better. Kon-yu didn’t know what “worse” looked like, but before the end of the week, she writes, “I was having suicidal thoughts and I could not stop seeing images of babies being hurt”.

Her partner took her to the hospital emergency department. Kon-yu signed herself into the mental health unit and stayed there two nights.

A disposable container

Part of the problem, Kon-yu reflects, is that every doctor she encountered in her first trimester had focused solely on the welfare of her “unborn child”. It was not until week 12 that she found Lila, a doctor who recognised that Kon-yu mattered and promptly told her that in any pregnancy the “mental health of the mother was the most important thing”.

“Lila saved my life,” writes Kon-yu. “She saved my daughter’s life. I’m certain of it.”

It is confronting to read about 21st century medical professionals who appear unable to identify or respond adequately to mental health concerns. It is equally disturbing – but, somehow, less surprising – to read about medical professionals who fail to treat a pregnant woman as a fully human person, instead treating her as an apparently disposable container designed to carry around a precious embryo.

Kon-yu’s new book combines memoir with political insights into the gender biases that structure pregnant women’s experiences. It scrutinises the social and cultural discourses that shape their bodily experience and the medical treatment they receive.

Historically, structural sexism in the medical profession has led to the marginalisation of women’s legitimate health concerns, with chronic and debilitating pain dismissed as drama or emotion. Stereotypically, culture tells us pain is something women are meant to tolerate. And some doctors listen to the culture, instead of their female patients – pregnant or otherwise.

As Australian surgeon Nikki Stamp has written: “For virtually the whole of its existence, medicine has disenfranchised women.” Although medicine and its institutions have modernised, “it remains, at times, paternalistic and patriarchal”.

A significant part of the difficulty, according to Kon-yu, is a medical culture that is myopically focused on birth, with its “inbuilt dramatic tension”. This results in little meaningful discussion of a pregnant woman’s well-being apart from the well-being of her “unborn child”.

In many ways, the sell-out April 1965 issue of Life magazine with its cover photograph, “Fetus 18 Weeks”, marked this shift in the cultural imagination of childbirth. As Kon-yu puts it, the photograph of a foetus in a sea of amniotic fluid, eyes closed, tiny fists pressed against its chest, looked like a “solo adventurer, floating among the stars”. When it appeared, NASA was embarking on its conquest of space and medical ultrasounds were in their own infancy. The photograph seems to gesture at a heroic, almost cosmic dimension of human existence.

What is less discussed is that this “solo adventurer”, depicted as if at the beginning of its life journey, was – detached from its mother – already dead. All the photographs – except one – were of recently miscarried or terminated foetuses. The hospital the photographer worked with would contact him so that a new foetus could be photographed within a few hours.

At a deeper level, this idea of the foetus as a “solo adventurer” plays into an impoverished kind of political individualism. Pregnancy poses an uncomfortable challenge to the disembodied, individualist and – let’s face it – pale, stale and male models of subjectivity that are enshrined in post-Enlightenment philosophy.

The fact that, as philosopher Iris Marion Young argues, “the discourse of pregnancy omits subjectivity” is unsurprising, given the historic exclusion of women’s experiences from the canons of philosophy, science and culture.

The result, as Kon-yu writes, is that even when doctors are aware there are two patients in any pregnancy (the mid-century paediatrician Donald Winnicott famously said there is “no such thing as an infant”, only an infant and its mother) medical science tends to privilege the foetus as “medically and technically by far the more interesting [patient]”.

Historical perspectives

This was not always the case.

The Cost of Labour contains some riveting details about the way women in industrial nations have changed the way they give birth. The manner in which Western women are accustomed to give birth is, as Kon-yu writes, only 300 years old.

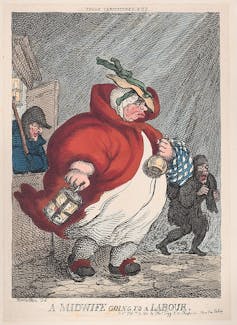

Public domain

Before the 18th century, caring for pregnant women was a female-dominated occupation; births were attended by midwives and female relatives. Women devised ergonomic solutions for childbirth. They delivered babies in flexible hammocks, threw ropes across beams, used poles for support and invented birthing stools. Midwives crouched down, taking advantage of biology and gravity.

It was only with the invention of the “laying-in hospital” in the 18th century that the balance of power shifted to male physicians, who clawed obstetrics away from midwives. In some hospitals, the default option is still for women to give birth flat on their backs, with legs in the air, suspended by stirrups. Historically, this change took place for the convenience of male physicians, not for the ease and comfort of the mother.

Ultimately, modern medicine would dramatically reduce maternal mortality and infant deaths. This important fact should not be ignored. But in the early days of the “laying-in” hospitals, the spread of germs saw maternal mortality rise. Physicians blamed women. They painted them in iodine, shaved their pubic hair, gave them enemas and forbade contact between mothers and their newborn babies.

It should come as no surprise that women were barred from medical training until the late 19th century.

Women at risk

When Kon-yu started writing, it seemed as if trauma was being always being researched elsewhere – intergenerational trauma, the trauma of racial discrimination, migration and detention, the Stolen Generations. But “nowhere,” writes Kon-yu, “do we speak of pregnancy as an experience which can traumatise people”.

This is the feeling she describes:

…suddenly, going to the supermarket by myself made me feel panicked. I stopped driving, and my world shrank to my living room, doctor’s surgeries, and the houses of a few close friends.

It was only after she met her doctor, Lila, who referred her to a perinatal psychiatrist, that “little by little I crawled out of that dark space”. As she did, she turned an intersectional feminist lens on the “concerning assumptions [that] have found their way into the foundations of the medical care we offer pregnant women”.

Kon-yu wryly describes herself as a “brown” woman who is “not too brown”: a woman from a Mauritian and Sicilian background, but with what she calls “white-passing privilege”. She is deeply attuned to the additional barriers that diverse women face which prevent them from accessing safe, sensitive and culturally appropriate services.

Women more at risk include LGBTIQ+ families, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, and culturally and linguistically diverse families. Not only does discrimination and isolation throw up additional barriers to seeking help – Kon-yu argues that in many instances, culturally safe, sensitive and appropriate care for pregnant women is simply not available.

Kon-yu names one innovative program designed with the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in mind, combining traditional practices of “borning” on Country with appropriate medical care. Despite its success, funding for the program has dwindled.

The Cost of Labour is a brave book. It does not shy away from difficult subjects, foregrounding Kon-yu’s own lived experience of perinatal trauma to draw attention to the cultural and gender biases in the medical care that is offered to pregnant women.

“I’ve talked about my pregnancy experience openly,” Kon-yu writes, “feeling that nobody benefits from silence or from the proliferation of happy stories out there.”![]()

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.