02 Feb here’s how to improve access for kids to extracurricular activities

The kids who’d get the most out of extracurricular activities are missing out, report Alexander William O’Donnell and Gerry Redmond

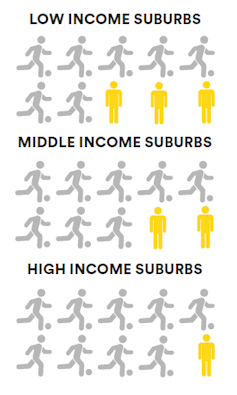

One-third of Australian children aged 12 to 13 in low-income suburbs do not take part in any extracurricular activities. That’s 2.5 times as many as those from higher-income suburbs – only 13% of them don’t take part – according to research we will present next week to the Australian Social Policy Conference. Yet research also shows it is children from disadvantaged backgrounds who are likely to benefit most from taking part in extracurricular activities.

Most children in Australia play a sport or take part in an extracurricular activity like dance, drama or Scouts. All of these activities can benefit their health and academic outcomes. For these children, such activities are typically available, accessible, affordable and safe.

However, many children who live outside major cities or in poorer suburbs face major barriers to participation. Cost is one obstacle. A Mission Australia report shows young people whose parents are not in paid work have low rates of participation in sport and cultural activities.

Poor public transport access is another barrier. Low-income suburbs also often lack clubs and facilities to run extracurricular activities.

Author provided

What help do governments offer?

State and territory governments provide vouchers or subsidies to help families cover some of the costs of such activities. But the rules of these schemes can be arbitrary and inconsistent, and tackle only some of the barriers to participation. The schemes often exclude non-sporting activities, despite the academic and psychological benefits matching or exceeding those provided by sports.

The vouchers can typically be used to part-cover registration fees. Their value varies around the country:

- $100 per year in South Australia

- $150 per year in Queensland

- $200 per year in New South Wales, Northern Territory and Tasmania

- $300 per year in Western Australia

- up to 100,000 $200 vouchers that can be claimed up to four times in 2021-22 in Victoria.

Author provided

In some states and territories (Qld, Tas, Vic, WA) vouchers are restricted to children named on health care cards or pensioner concession cards. In others (NT, NSW, SA) the vouchers are more freely available.

When vouchers are widely available, affluent families and communities tend to use them more. Low-income families may not have the money to cover the full costs of taking part in an activity, or may be unaware of voucher schemes, despite their greater need for help with costs.

Sports vouchers do increase sport participation. Still, hefty out-of-pocket expenses remain.

Some clubs have taken imaginative steps towards reducing these costs, such as trading parent volunteer time for fees. But such approaches are not widely used and are not perfect.

Support is needed beyond sport to close the gap

While sports are great for development, lots of children also enjoy taking part in non-sporting activities. Research shows the academic and psychological benefits of these activities are equivalent to or can exceed those provided by sports.

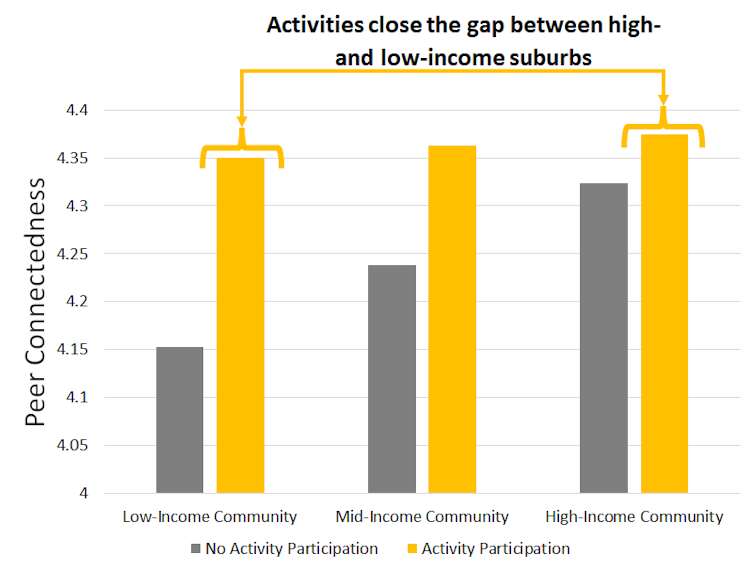

In our research being presented next week, we found that children in more affluent communities typically reported high peer connectedness and school belonging, regardless of participation in activities. But children in disadvantaged communities who take part in extracurricular activities reported significantly higher outcomes compared to non-participants. They almost closed the gap with children in high-income communities. This effect emerged regardless of whether the activity was sporting or non-sporting.

Despite non-sporting activities having comparable benefits, most vouchers are limited to “sport and active recreation”. This generally includes dance but excludes other creative activities.

Only two jurisdictions (NT and NSW) explicitly offer vouchers that cover arts, music and cultural activities. The NT urban sport voucher scheme includes cultural and arts activities. NSW offers a universal $100 per year Creative Kids voucher (in addition to its Active Kids sports voucher). It’s specifically aimed at arts and cultural activities.

Not all children’s interests involve kicking a ball or doing laps in a pool. Arbitrarily excluding non-sporting activities from government subsidies may prevent disadvantaged children taking part in the activities they enjoy most. In contrast, more affluent families are better able to support these activities without government support.

Extracurricular activities occur outside the classroom and are not mandated by a set curriculum. Participation is therefore voluntary and the decision is driven by interests and a desire to be around friends.

In deciding what activities to subsidise, governments are taking this decision away from children and their parents. Governments need to ensure the needs and wants of children are taken into account when providing subsidies.

Subsidies alone are not enough

Expanding subsidies to cover more expenses and activity types will increase participation. But subsidies can’t solve all the issues.

For a start, most activities cannot happen without suitable sports grounds or indoor spaces. For example, a lack of change rooms sometimes hinders efforts to increase female sport participation. Similarly, children in poorer suburbs may not feel welcome in other suburbs where activities are taking place.

Local councils and schools have traditionally provided the infrastructure for extracurricular activities. However, some councils have gone a step further in co-ordinating access to these activities. For example, the City of Playford in the northern suburbs of Adelaide partnered with government, philanthropic and community organisations to encourage all ten-year-olds to take part.

Some non-government organisations and community leaders have also developed promising local initiatives. Evaluation of these initiatives can hopefully inform future efforts around the country. We need a broader and more generous approach to help local organisations build thriving communities.

Experts and advocacy groups agree that all children should have opportunities for extracurricular activity. Australia needs more schemes that enable children to take part in activities of their choice.![]()

Alexander William O’Donnell, Research Associate, College of Business, Government and Law, Flinders University and Gerry Redmond, Professor, College of Business, Government & Law, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.