21 Jul How well does the new Australian Curriculum prepare young people for climate change?

How well does the new Australian Curriculum prepare young people for climate change? Researchers Kim Beasy, Chloe Lucas, Gabi Mocatta, Gretta Pecl and Rachel Kelly give a pleasing update.

You’d be forgiven for not having heard about the long-awaited new Australian Curriculum, which was released with little fanfare in the midst of the election campaign. But this update to the national curriculum (9.0), for foundation to year 12 students, is hugely significant. It will guide the education of young Australians for the next six years, which could encompass a child’s whole primary or secondary school education.

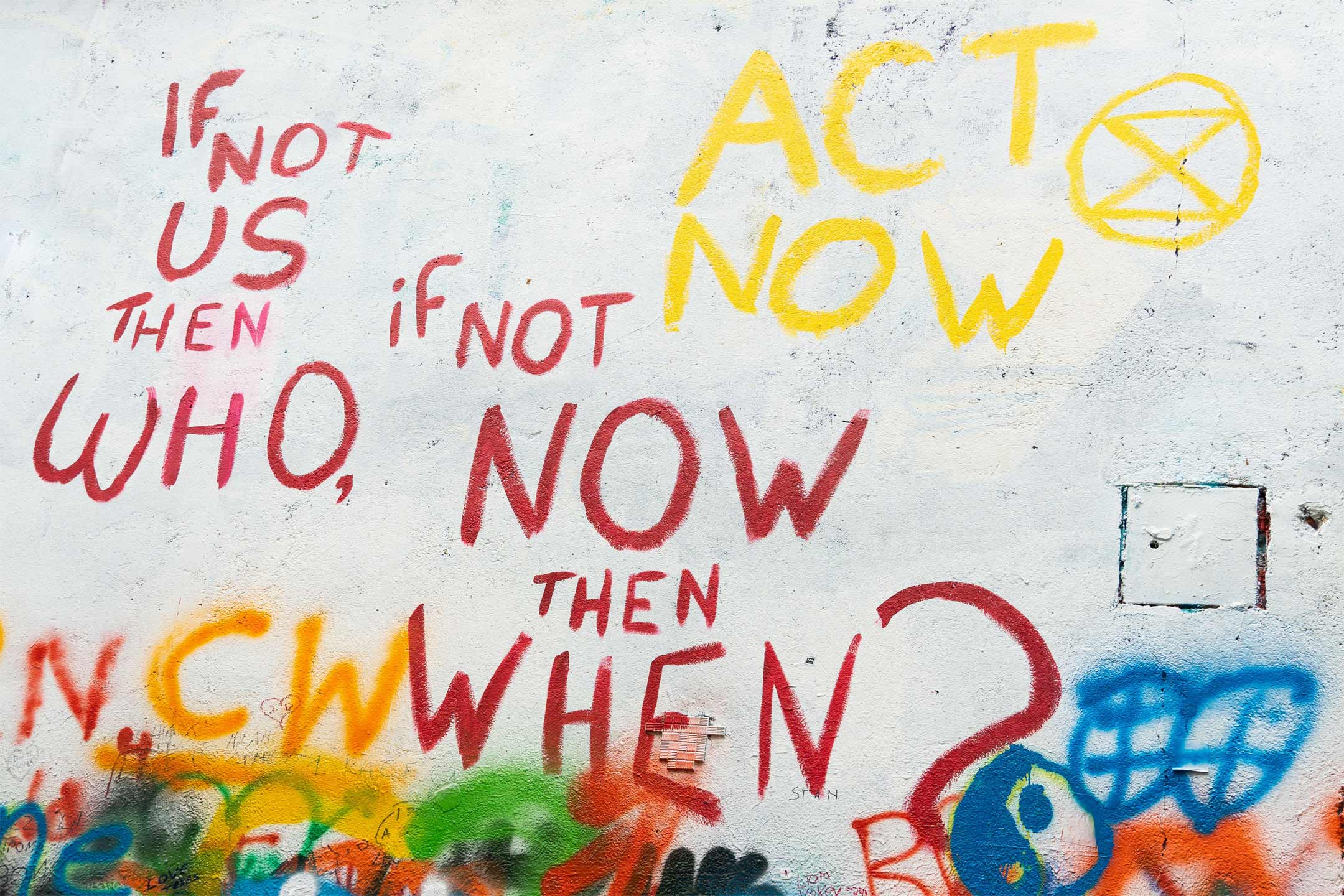

Education fundamentally prepares children for life, so it should be expected to address the existential issues of our time. On our current trajectory, climate change will drastically affect children’s health, wealth and job futures. Today’s children face up to seven times as many extreme weather events as people born in the 1960s experienced.

If we are to tackle climate change and adapt to the impacts that are already unavoidable, then children need to be educated for a changing future. Until now, however, this subject matter has been largely missing from the Australian Curriculum.

We know young people are overwhelmingly concerned about climate change. Students, parents and academics have been calling for a greater focus on climate change in all areas of school learning.

Our research project, Curious Climate Schools, has involved 1,300 Tasmanian school students to date in student-led climate literacy learning. It shows current teaching leaves students with many unanswered questions about climate change. And, from our lightning analysis of the new curriculum, it seems it won’t routinely deal with the kinds of questions students are asking.

www.curiousclimate.org.au/schools

Climate change content has increased

The good news is that the new curriculum does pay more attention to climate change. The old curriculum had a total of four explicit references to “climate change”. Whether it was covered in the classroom depended on the knowledge and beliefs of teachers.

In the new curriculum we counted 32 references to climate change across diverse subject areas: civics and citizenship, geography, history, science, mathematics, technologies, and the arts. This means students have more opportunities to learn about climate change, and teachers have more direction on where and how to teach it.

For example, in civics and citizenship, secondary school students can now learn about global citizenship by studying the campaigns of youth activists like Greta Thunberg and the work of Indigenous Australian climate campaigner Amelia Telford. They can also learn about global climate governance, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Climate change is also used in innovative ways in the new curriculum. In maths, for example, it’s presented as a context for teaching students how to use statistical evidence.

However, our analysis of climate change in the new curriculum also reveals it is dominated by a science focus. We counted 21 references to climate change in science and technology learning areas, but only nine in humanities and social science learning areas and two in the arts learning area.

Our work with students through Curious Climate Schools shows their wide-ranging questions about climate change encompass ethics, politics, their careers and their futures. Students are interested in climate science and projected impacts, but have more questions about the urgency of action and what can be done. This illustrates that learning about climate change must be suffused through all subject areas if students are to become climate literate.

Many young people want to contribute their skills and knowledge to climate action in their future careers. We need to show them, through the curriculum, that in whatever subject area their interests lie – health, arts, law, engineering, ecology or many other fields – they will be able to use their talents to tackle the climate crisis.

Worryingly, explicit mentions of climate change are still missing from the primary school curriculum. The Curious Climate Schools project found upper primary teachers had the most interest and capacity to bring climate learning into their classrooms, because they were more able to explore the complex and interacting issues of climate change across subject areas.

Worryingly, explicit mentions of climate change are still missing from the primary school curriculum. The Curious Climate Schools project found upper primary teachers had the most interest and capacity to bring climate learning into their classrooms, because they were more able to explore the complex and interacting issues of climate change across subject areas.

Equipping teachers for holistic climate teaching

Climate change is causing legitimate and increasing anxiety for many young people. Many students leave school feeling betrayed and disempowered because their climate concerns are not being heard or taken seriously. The new curriculum does not adequately acknowledge or act on the significant emotional impacts of growing up in a changing climate.

This leaves teachers, who may become the bearers of bad news to many students, in a difficult position. In our interviews with teachers they told us they don’t feel confident to teach about climate change or to manage their students’ anxiety as they discover how climate change will affect their futures.

Governments and universities have a responsibility to ensure teachers have the knowledge and skills to teach their students holistically about climate change. They can’t be expected to do this without training or resources.

The new curriculum moves towards addressing climate change in the classroom, but climate teaching in schools must be much more ambitious, given the urgency and enormity of the problem. This needs to be supported first by building teachers’ own knowledge about climate change. It also means equipping schools with resources that empower their students to become active citizens in a changing climate.![]()

Kim Beasy, Lecturer in Curriculum and Pedagogy, University of Tasmania; Chloe Lucas, Research Fellow, Geography, Planning and Spatial Sciences, University of Tasmania; Gabi Mocatta, Research Fellow in Climate Change Communication, Climate Futures Program, University of Tasmania, and Lecturer in Communication – Journalism, Deakin University; Gretta Pecl, Professor, ARC Future Fellow & Director of the Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania, and Rachel Kelly, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Future Ocean and Coastal Infrastructures (FOCI) Consortium, Memorial University, Canada, and Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.