30 Nov Kids dressing up as older people is harmless fun, right?

No, writes Lisa Mitchell, it’s ageist, whatever Bluey says.

A child once approached me, hunched over, carrying a vacuum cleaner like a walking stick. In a wobbly voice, he asked:

Do you want to play grannies?

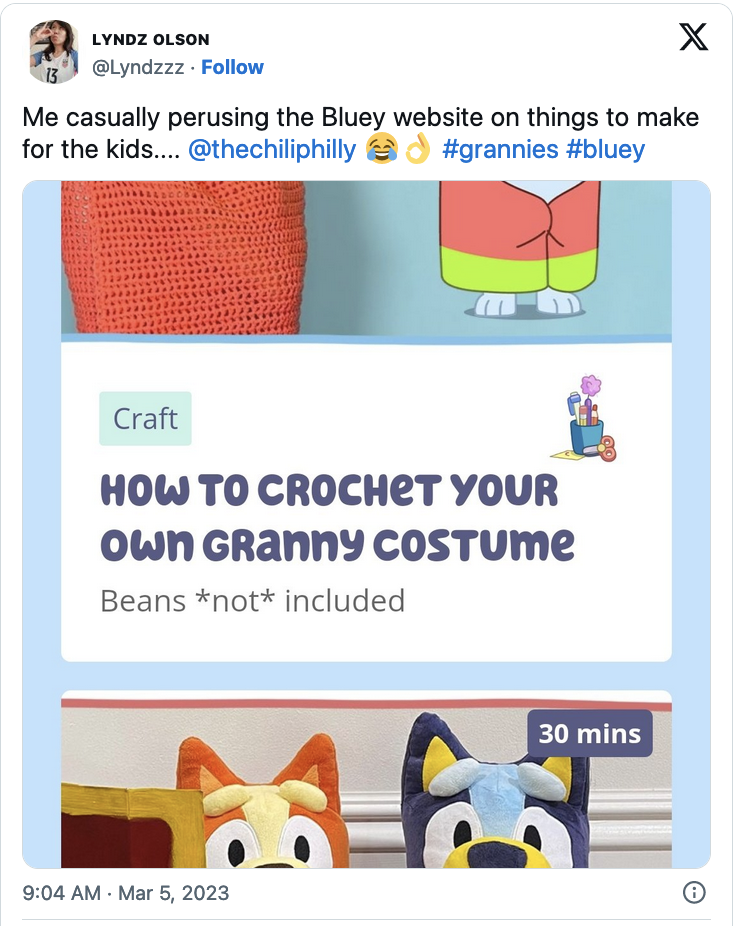

The idea came from the children’s TV show Bluey, which has episodes, a book, magazine editions and an image filter about dressing up as “grannies”.

Children are also dressing up as 100-year-olds to mark their first “100 days of school”, an idea gaining popularity in Australia.

Is this all just harmless fun?

How stereotypes take hold

When I look at the older people in my life or the patients I see as a geriatrician, I cannot imagine how to suck out the individual to formulate a “look”.

But Google “older person dress-ups”, and you will find Pinterests and Wikihow pages doing just that.

Waistcoats, walking sticks, glasses and hunched backs are the key. If you’re a “granny”, don’t forget a shawl and tinned beans. You can buy “old lady” wigs or an “old man” moustache and bushy eyebrows.

This depiction of how older people look and behave is a stereotype. And if dressing up as an older person is an example, such stereotypes are all around us.

Shutterstock

What’s the harm?

There is some debate about whether stereotyping is intrinsically wrong, and if it is, why. But there is plenty of research about the harms of age stereotypes or ageism. That’s harm to current older people and harm to future older people.

The World Health Organization defines ageism as:

The stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) towards others or ourselves based on age.

Ageism contributes to social isolation, reduces health and life expectancy and costs economies billions of dollars globally.

When it comes to health, the impact of negative stereotypes and beliefs about ageing may be even more harmful than the discrimination itself.

In laboratory studies, older people perform worse than expected on tasks such as memory or thinking after being shown negative stereotypes about aging. This may be due to a “stereotype threat”. This is when a person’s performance is impaired because they are worried about confirming a negative stereotype about the group they belong to. In other words, they perform less well because they’re worried about acting “old”.

Shutterstock

Another theory is “stereotype embodiment”. This is where people absorb negative stereotypes throughout their lives and come to believe decline is an inevitable consequence of aging. This leads to biological, psychological and physiological changes that create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I have seen this in my clinic with people who do well until they realise they’re an older person – a birthday, a fall, a revelation when they look in the mirror. Then, they stop going out, exercising, and seeing their friends.

Evidence for “stereotype embodiment” comes from studies that show people with more negative views about ageing are more likely to have higher levels of stress hormones (such as cortisol and C-reactive protein) and are less likely to engage in health behaviours, such as exercising and eating healthy foods.

Younger adults with negative views about ageing are more likely to have a heart attack up to about 40 years later. People with the most negative attitudes towards ageing have a lower life expectancy by as much as 7.5 years.

Children are particularly susceptible to absorbing stereotypes, a process that starts in early childhood.

Shutterstock

Ageism is all around us

One in two people have ageist views, so tackling ageism is complicated, given it is socially acceptable and normalised.

Think of all the birthday cards and jokes about ageing or phrases like “geezer” and “old duck”. Assuming a person (including yourself) is “too old” for something. Older people say it is harder to find work, and they face discrimination in health care.

How can we reduce ageism?

We can reduce ageism through laws, policies and education. But we can also reduce it via intergenerational contact, where older and younger people come together. This helps break down the segregation that allows stereotypes to fester. Think of the TV series Old People’s Home for 4-Year-Olds or the follow-up Old People’s Home for Teenagers. More simply, children can hang out with their older relatives, neighbours and friends.

We can also challenge a negative view of ageing. What if we allowed kids to imagine their lives as grandparents and 100-year-olds as freely as they view their current selves? What would be the harm in that?![]()

Lisa Mitchell is a geriatrician working in clinical practice. PhD Candidate at The University of Melbourne studying ethics and ageism in health care. Affiliate lecturer, Deakin University.

Main Image: Shutterstock

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.