25 Jul Looking at Difference: Going By The Book

Mary Curtin tracks her autistic son’s transition to school through his teacher’s written commentary.

Every day [Andrew] brings home a ‘communication book’, in which his teacher or aide writes a few lines about his day. They note how he behaved in class, interacted with the other children or coped with any changes in routines.

It is 3.30pm and we have just arrived home from school. I am eagerly searching in my son’s bag. I remove the lunch box, emptying out the uneaten and half-eaten snacks I so diligently put in that morning, the leaking drink bottle and the scrunched-up drawings, which I carefully smooth out to admire later. Then I find ‘the book’. I take a deep breath and open it, hoping for good news.

Andrew was diagnosed at the age of three-and-a-half

Andrew, who has autism spectrum disorder, started going to the local primary school this year. Every day he brings home a ‘communication book’, in which his teacher or aide writes a few lines about his day. They note how he behaved in class, interacted with the other children and coped with any changes in routines. These few lines, which I so keenly read each afternoon, can change the colour of my day and make me feel justified (or not) in our decision to send Andrew to a mainstream school.

When Andrew was diagnosed at the age of three-and-a-half, having a ‘label’ to put on his often aggressive, frustrating or simply baffling behaviour was both a relief and a burden.

We are better now at noticing when he is becoming overwhelmed by noises or confusion and can head off most meltdowns before they occur. I can sort of understand that his obsession with pressing the buttons on the traffic lights (and tantrums if someone else presses it first) is his way of coping with the too-loud trucks and cars whizzing past. His speech, after years of therapy, is now reasonably clear and he can talk to other children rather than resorting to pushing and hitting as he often did as a preschooler.

However, coming to terms with the fact that our child is different, and will be like that for the rest of his life, is difficult. Our older daughter sailed through her first nine years with few hiccups on the way – something we took completely for granted until we embarked upon the rockier path with Andrew.

At the end of the most trying days, I would often be in tears

During the worst period following the diagnosis, I could not imagine him coping at school or that anyone else would be willing to put up with him for six hours a day.

At the end of the most trying days, I would often be in tears worrying about how his life and ours were forever blighted by his condition. Would he be able to go to school, get a job, find someone to love, have any semblance of a ‘normal’ life?

His teacher has put a small gold star in the corner.

Yet here I am reading in his communication book: “Andrew had a great day today. Sat for 10 minutes on the mat at storytime and was able to complete two activity sheets with only a little help. At lunchtime, he had a good play in the sandpit with Alex.” My heart is beating a bit faster as I make a cup of tea and sit down to read the words again and to admire the worksheet he has brought home.

There is a coloured scribble inside the lines of the picture and he has written his name at the top. His teacher has put a small gold star in the corner. This by my boy, who until recently would refuse even to hold a pencil or sit still at a table.

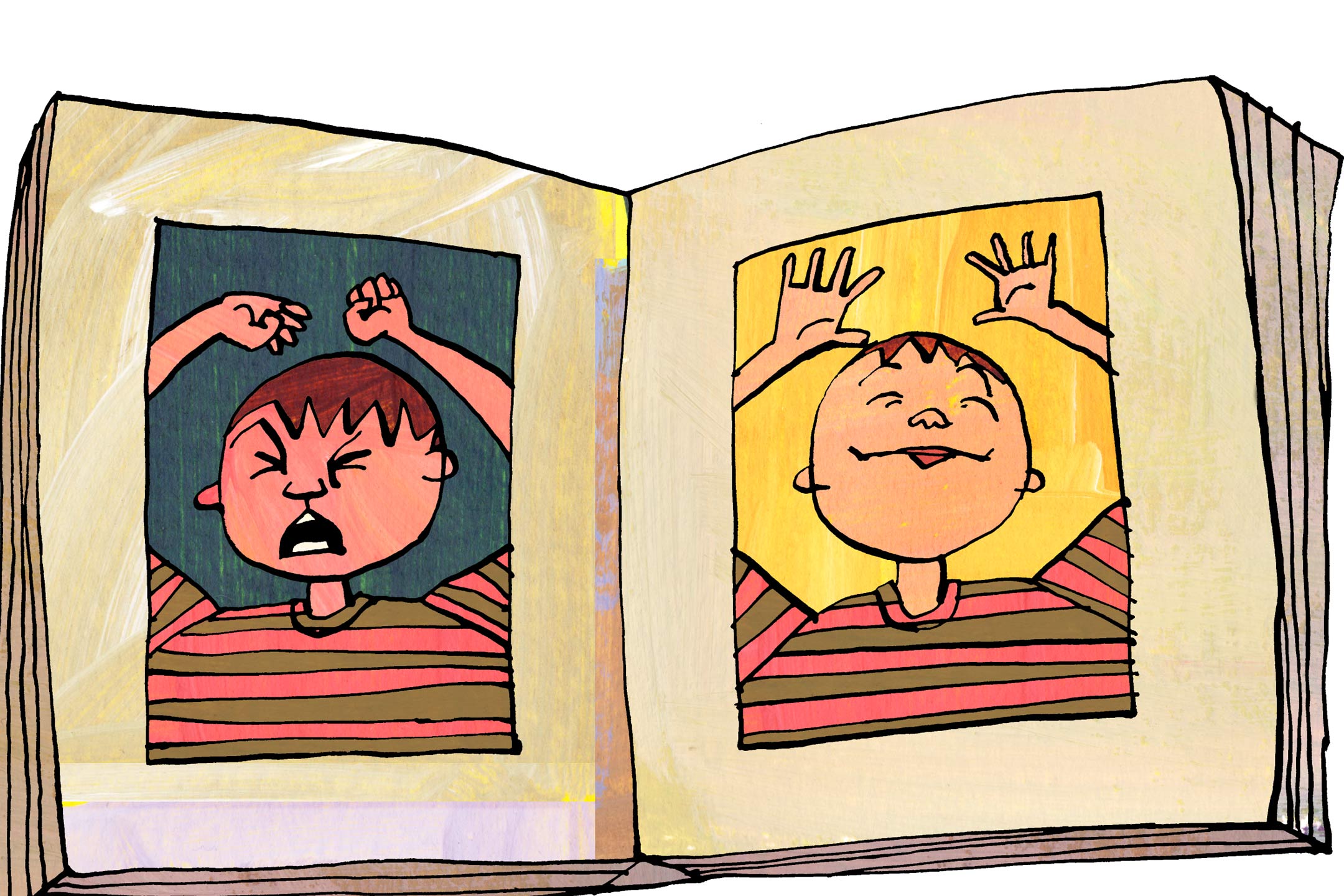

I know quite well that tomorrow the communication book might have a different theme. Despite the teacher’s efforts at being upbeat in her comments, it is not hard to read between the lines when it has been a bad day. On those days he can be hypersensitive to any sensory stimulation: his classmates talking too loud, chairs scraping on the floor, the teacher telling him to finish something before he is ready – any of these things can send him spiralling out of control.

I know there are times when he lashes out at the other kids, bursts into sobs for no obvious reason or even hides under the table. These are the days when it takes all of his teacher’s skill and patience to calm him down and help him get back on track. We are so lucky to have a great teacher who can do this and who tries to understand the causes of this behaviour.

Sometimes there are even several ‘good’ days in a row

Sometimes there are even several ‘good’ days in a row, but this can be followed by a bad week, making me feel as if we have taken one step forward and two steps back.

Like many autistic children, Andrew thrives best on routines and a predictable environment. He has to work hard to adjust to changes. So we know to expect some difficult behaviour during the first week of the school holidays and also the first week back at school for the new term. Warning him about changes, and preparing him for them, can help to alleviate some of his anxiety.

When Andrew comes home from school, I try to restrain myself from bombarding him with questions. He has already adopted a typical schoolboy monosyllabic nonchalance and will answer with a shrug or a “dunno” when I ask him what he did that day.

As I dig the communication book out of his bag, I am glad that I at least have this glimpse into his new world, although part of me looks forward to the day when it will no longer be needed.

Names have been changed, including the authors.

Illustration by Alastair Taylor