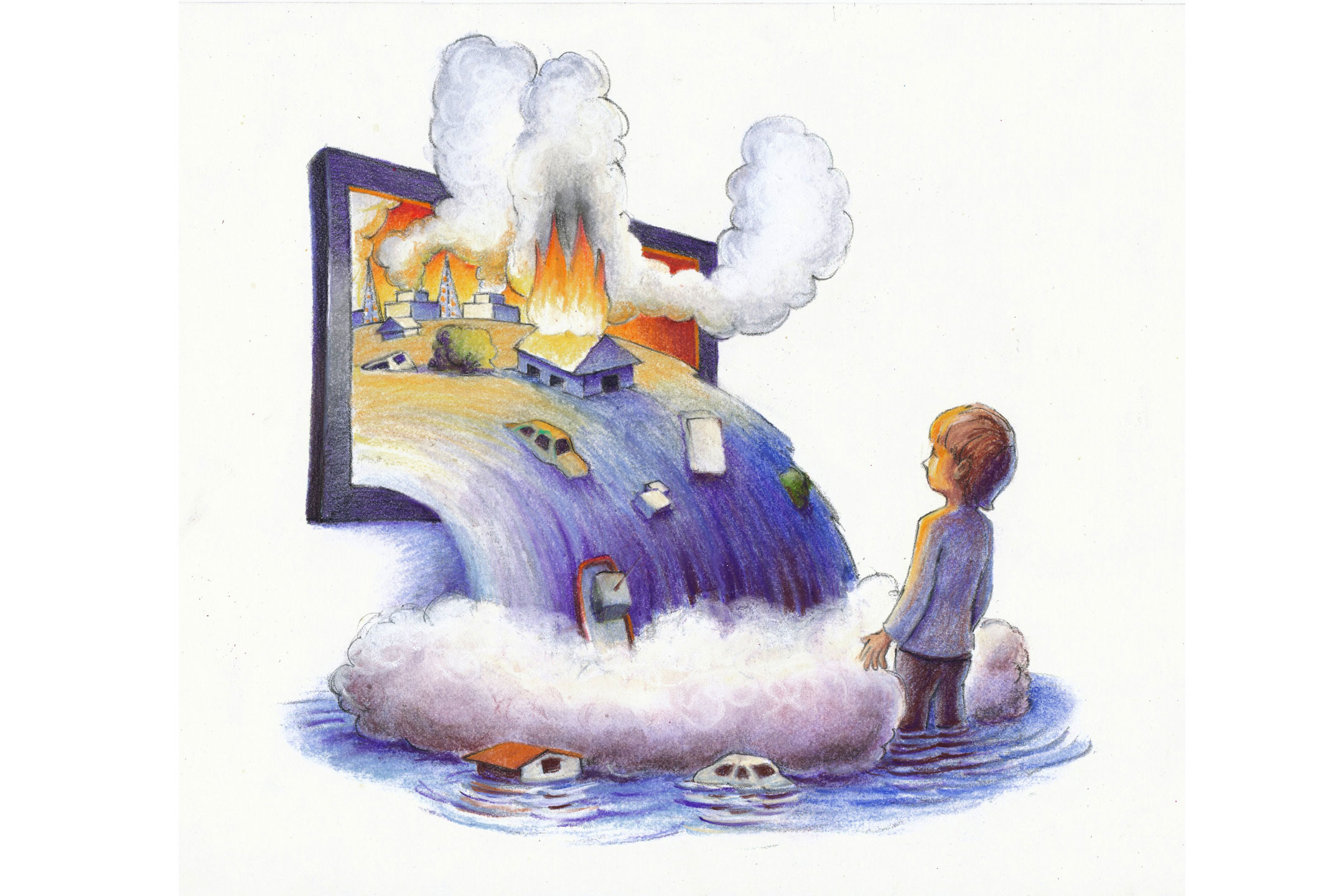

18 Apr Scary screen time and it’s affect on young children

Viewing our media from a child’s perspective can be alarming, writes Wayne Warburton.

Since the start of the year, we have witnessed a series of natural disasters, both here and overseas. We have watched families dislocated and financially ruined as floods swept through parts of Australia. We have also watched the horror of people trapped in the rubble following the Japanese earthquake and the massive destruction of international aggression.

Most adults I know find many of these scenes upsetting and hard to watch. Alongside them (and sometimes alone), many Australian children have watched the same events on news programs and news updates that air throughout the day. More and more parents have been asking me of late if this can harm their child.

Typically, their common-sense notion is that watching too much upsetting media must have some negative impact on children. But they would like to know what the scientific research indicates.

Upsetting media can become more fearful in both the short and long term

As I find in many areas of psychology, it turns out that the common-sense approach is the one that research also suggests makes sense. In this case, there is a lot of research showing that children who are exposed to upsetting media can become more fearful in the short and long term, that they can develop enduring attitudes whereby they see the world as more threatening than it really is, and that they tend to think that other people want to hurt them. These sorts of fears and attitudes have been linked with other negative consequences such as unhappiness, depression, anxiety, trauma, problems in relationships, and even suicide.

The researcher who has made this stream of enquiry about her life’s work is Professor Joanne Cantor, a research psychologist specialising in media and communications and director of the Center for Communication Research at the University of Wisconsin. Across 30 years of research, Cantor has amassed an impressive and consistent array of findings that have linked exposure to upsetting media with short and long-term fears and described changes in children’s responses to media as they grow older. She has also catalogued general media themes that children find upsetting.

I have found her work to be particularly relevant to my family. Both my young children have been upset by things they have seen in the media in recent months, but each has been upset by different aspects. This accords with Cantor’s research, which shows that responses to upsetting media depend on a child’s cognitive and emotional development.

Younger children are ‘concrete’ thinkers and make judgements based on the obvious characteristics of a situation. They are afraid of media portrayals of creatures with obviously frightening characteristics, such as monsters and witches, despite the low likelihood of encountering such creatures in real life. This is just the way my son responds – he will run and hide when the giant robot appears in Here Comes The Bride or when Alex the lion discovers his inner beast and lets out a huge roar in Madagascar.

In addition, as younger children cannot yet think in abstract terms, they might think that an event seen repeatedly on television is actually a series of new events of a similar type occurring again and again. This means that repeated coverage of natural disasters can have a particularly traumatic effect on younger children.

Children are scared by interpersonal violence, war and suffering

Research suggests that as children develop the capacity to empathise with others (starting at about the age of four) and to understand abstract concepts (at about the ages of seven or eight), they start to become less afraid of creatures and situations that cannot realistically harm them. However, they become more afraid in response to media portrayals of situations that they can imagine, resulting in personal harm to them or people they know.

Children are especially likely to become upset if some aspect of what they see reminds them of their own family and friends. This is how my daughter often responds. She has been upset by the plight of children and families in recent disasters and has also been concerned that events such as cyclones or earthquakes could affect our family.

Even though the aspects of media that upset children differ according to a child’s age, the types of media subject matter that children find upsetting and frightening are similar across ages. In particular, children are scared by interpersonal violence, war and suffering, fires and accidents (including displays of dangers and injuries and of fearful people and people in danger), and fantasy characters and distortions of natural forms.

In the long term, exposure to this sort of media has two types of effects: the first is fears and phobias; the second is stable changes to the ways in which children view the world. In terms of fears, about 25 to 33 per cent of adults have an enduring fear or phobia stemming from something they experienced in the media as a child. I am one of them.

Avoiding the object of fear

I remember, as a teenager, hearing a media report of an alleged incident where a razor blade had been inserted into a water slide with chewing gum. I imagined the horrific injuries that would have resulted from this and have never been able to bring myself to use a water slide since, despite discovering that the razor-blade story was an urban myth. As with me, these fears usually result in avoiding the object of fear – but they can also involve recurring nightmares and sleep disturbances.

As a parent, the effect I find most worrying is that children can also develop enduring changes in the way they think about the world. It is well documented that higher levels of media exposure are linked to the belief that the world is a dangerous and frightening place, a sense of being in danger in the real world, a greater expectation of being involved in real-world violence, and a greater tendency to interpret others’ behaviours as deliberately hurtful, even when they are intended as innocent. These beliefs, in turn, can lead to children being more hostile and aggressive and can have negative effects on mental health and relationships.

For this reason, I am concerned about children (including my own) having too much exposure to violent, frightening and upsetting media. I tend to prefer a strategy of limiting access for young children and encouraging older children to learn to self-regulate their media exposure, to watch purpose-made children’s news programs such as the ABC’s Behind The News, and to avoid adult news programs.

Sometimes, though, kids do see scary media, and the research suggests that a number of strategies are helpful. For younger children, taking them away from the upsetting media, giving them a cuddle, and engaging in physical activities such as holding onto a blanket or toy or getting something to eat or drink have been shown to be helpful.

Older children also like a cuddle, but are more able to talk things through. When my wife and I talk to our daughter about upsetting things she has seen, we like to find out exactly what it was that she found upsetting so that we can talk directly about that aspect of the media.

Talking through her experience often involves putting an event into a broader context, providing helpful information (for example, emergency crews and the army are on standby and are ready to move in and help), and letting her know that the adults involved have things in hand. We also talk about the nature of media (the way that ‘sensational’ events are prioritised in media coverage and tend to seem more common than they really are) and discuss the likelihood of scary things actually happening to our family.

My wife has also encouraged our daughter to take positive action regarding the scary stuff she has seen. For example, after seeing coverage of a recent disaster, our daughter sent money to a charity to help. She googled the different organisations, chose the one she wanted to donate to, filled in the forms and pressed ‘send’. This sort of positive response seems to restore a sense of agency and control and can be helpful in reducing fears.

In the end, I think of media as being like food for the brain. With food, we need a balanced diet. Some food is good for us daily, some food should be eaten only occasionally, and some things should never be eaten. A balanced media diet is also important, and in order to achieve this for our children, we need to understand the effects of scary media and manage their exposure to it.

Dr Wayne Warburton is deputy director of the Children and Families Research Centre at Macquarie University.

Illustration by Dale Newman