19 May Since when did councils ban books?

A Sydney council tried to ban books with same-sex parents from its libraries. But since when did councils ban books? asks Sarah Mokrzycki

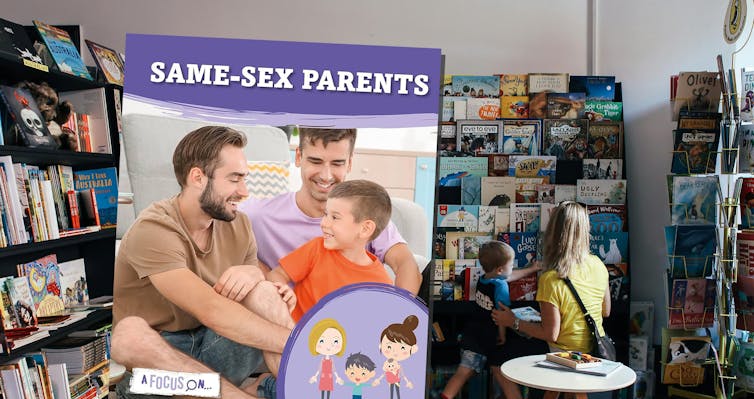

Western Sydney’s Cumberland city council recently reinstated a ban on all books depicting same-sex parents in its eight public libraries, after banning a book citing concerns over the “safety” of children.

The ban was originally passed (six votes for and five against, while four councillors were not present to vote) at a recent council meeting, and was spearheaded by councillor and former Cumberland mayor Steve Christou.

As a queer woman and foster mother to 12 children over the past decade, as well as a researcher on the connection between representation in children’s books and child welfare, I was disheartened to learn Christou had argued books about same-sex parenting “sexualised” children.

Presenting the council with a copy of the children’s picture book Same-Sex Parents by Holly Duhig, Christou said: “Our kids shouldn’t be sexualised […] This community is a very religious community, a very family-orientated community […]”

Christou said toddlers shouldn’t be “exposed” to same-sex content. His argument epitomises a particular social fallacy that children need to be “taught” about same-sex parented families at a specific, appropriate age.

This speaks to the idea of same-sex relationships as being unnatural or strange, and therefore something that requires explanation and consent to discuss. Conversely, heteronormative relationships are seen as natural and appropriate, and therefore something children are exposed to from birth without explanation.

This status quo does serious damage to children with same-sex parents as well as those without. It questions and dismisses the legitimacy of same-sex parented families, greatly limiting the extent children can see their families represented (in picture books as well as other media) and sending a clear message that their families aren’t “normal”. This, in turn, sends an equally clear message to their peers regarding the validity of same-sex couples as parents.

‘Welcome, belong, succeed’

MP Lynda Voltz and NSW Arts Minister John Graham have expressed concerns over the ban. Voltz believes it may breach the state’s Anti-Discrimination Act. Graham has accused the council of censorship, stating:

It is up to readers to choose which book to take off the shelf. It should not be up to local councillors to make that choice for them or engage in censorship.

Cumberland mayor Lisa Lake and councillor Diane Colman have raised similar concerns. Lake is “appalled and saddened” the ban has passed, stating: “As long as parents are loving families, that’s what’s important.”

Colman told Guardian Australia the ban contradicts the Cumberland city council motto “welcome, belong, succeed”. She said, “Bans like this indicate some people believe that isn’t the case.”

Censorship in Australia

Australia has a long and complicated history with censorship and book banning. The Trade and Customs Act of 1901 controlled the importation of books for most of the 20th century (and banned plenty along the way, including The Catcher in the Rye).

The Australian Classification Board began in 1970. If school boards, community members, or even politicians raise concerns about books, the board – a statutory body – makes a decision about the book’s suitability to be publicly available. The review board consists of a convenor, a deputy convenor and board members, and operates on a “majority-based decision-making procedure”.

It famously struggled with classifying the young adult graphic novel Gender Queer: A memoir by Maia Kobabe, challenged in 2023 by conservative commentator Bernard Gaynor, and ultimately found “appropriate for its intended audience” after appeal.

The book Christou used in his argument, Same-Sex Parents by Holly Duhig, is what is known as an “issue-based book”, meaning it outlines information rather than presents a narrative. It is recommended for children aged 5-7, and talks directly to the reader, saying:

A small number of people might treat people from same-sex families unfairly. This is not OK. All loving families are good … Remember, as long as you are happy, it doesn’t matter what other people think.

The overall theme appears to be simple reaffirmations of belonging for children in same-sex parenting families.

The actions of Cumberland council are unusual, to say the least. (Earlier this year, the same council passed a motion to ban drag queen “story time” events.)

But in America such library bans are apparently escalating. The key difference is that American libraries are run by their own boards, who dictate library policy. There have been reports of libraries “stacking” boards with “conservative appointees” and closing board meetings to the public.

In the US, attempts to censor books at public libraries increased by 92% from 2022 to 2023, accounting for about 46% of all book challenges in the US in 2023. As TV host John Oliver revealed this week, library staff there have experienced “a huge increase in harassment, with some baselessly accused of paedophilia for allowing certain books to be checked out”.

What next?

It remains to be seen what the fate of this banning could be. Its implementation may have impacted Cumberland library’s government funding, and action was taken by advocacy groups. Rainbow Families, an advocacy group for LGBTQ+ families in Australia, has reportedly spoken to the anti-discrimination board about the ban.

Ultimately, Cumberland’s ban is counter-intuitive. When children, and their families, are represented in books, it creates inclusivity rather than division, promoting a greater sense of community – and a better understanding of what makes a family.![]()

Sarah Mokrzycki, Sessional Academic, children’s literature and creative writing, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.