06 May The Government’s child-care subsidy plan: how it works and what it means for families

The federal government is pitching its 2021 budget as “women-friendly” writes Danielle Wood, Kate Griffiths and Owain Emslie. This week it announced a key feature of that – more money to make child care cheaper and boost women’s workforce participation.

The Coalition’s policy will increase spending on the child-care subsidy from July 2022 by an extra A$1.7 billion over three years. That is about a 6% increase on the current investment of $9 billion a year.

Key Changes

The policy has two main components.

First, it drops the “annual cap” that limits the total yearly subsidy to $10,560 per child for families with a combined income of more than $189,390. After that – generally, if they have their children in care for four or more days a week – they pay the full cost of care. These costs are often a big disincentive for women with high-earning partners to work more than three days a week.

Second, it boosts the subsidy for second and subsequent children in care by up to 30 percentage points (capped at 95%). This means families currently eligible for a 50% subsidy would now be eligible for an 80% subsidy on their second child if both children are aged under six. Older children using after school care are not eligible for any extra subsidy.

This will reduce fees for families paying some of the highest out-of-pocket childcare care costs – those with multiple children in long daycare.

So how does it work?

Consider a middle-income family where one parent earns $85,000 and the other parent earns $65,000, with two young children in daycare paying the average cost of $110 a day per child. Under the current scheme, they are eligible for a 60% subsidy for both children. So they pay $88 a day and the government pays $132.

Under the new policy, the subsidy will rise to 90% for the second child (with the first child still on a 60% subsidy). This means the parents will pay $55 a day for both children, and get a $165 subsidy. If they have the children in care for four days a week, they will be $132 a week better off.

Effect on workforce participation and family budgets

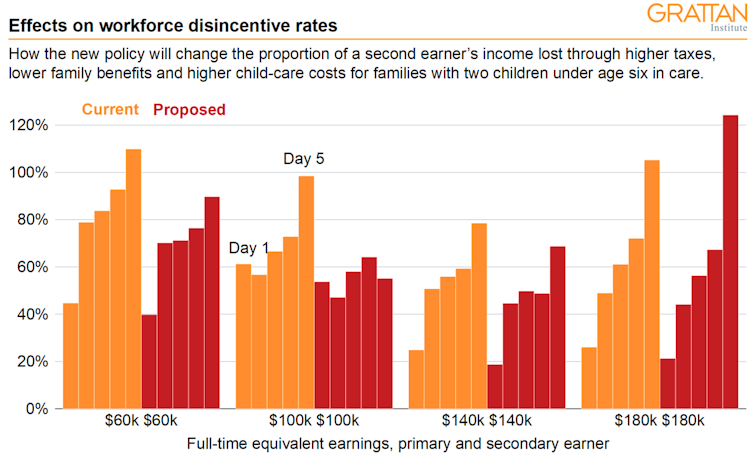

Currently, for families with two children in long daycare, the primary caregiver (typically the mother) can lose more than 80% – in some cases 100% – of take-home pay in the move to take a fourth or fifth day’s work. Child-care costs on those extra days are the main contributor.

The new policy reduces the disincentives for those families.

The first graph shows a family where the father earns $60,000 and the mother would earn the same if she worked full time. The current system means she loses 90% of what she earns on her fourth day and more than 100% on the fifth day.

The new policy will lower these “workforce disincentive rates”.

The mother will now lose 75% on the fourth day and 90% on the fifth day.

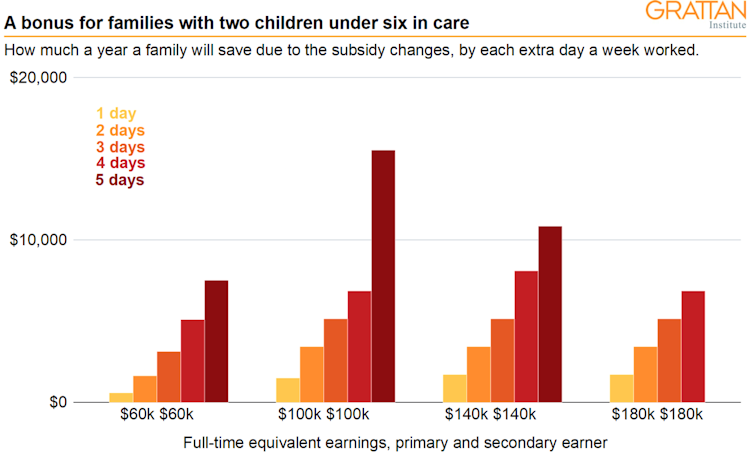

As the next graph shows, the family will be $5,000 a year better off if the second earner works four days, and $7,500 a year better off if she works full-time.

For a family where both parents have the potential to earn $100,000 working five days a week, the new policy will almost halve the current workforce disincentive rate for working the fifth day – from 100% to 55%.

This is because such a family will benefit from both the extra subsidy for the second child and the removal of the annual cap.

Workforce disincentives remain high even with the new policy. But it is a significant improvement on the status quo.

The flip side of a highly targeted policy is that it benefits only a small segment of families. On the federal government’s numbers, up to 270,000 families may benefit.

This compares with almost 1 million families now accessing some subsidised child care and many more who would like to access it if they could afford it.

Labor announced its child-care policy in the budget reply last year.

How the Coalition’s policy compare to Labor’s

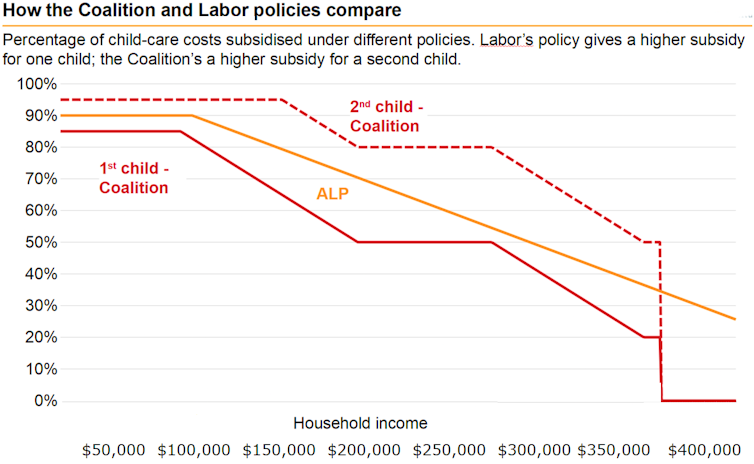

Like the Coalition’s, Labor’s policy removes the annual cap. But it also increases the base subsidy (for all children) to 90%. It also reduces the rate at which the subsidy reduces as family income increases.

This is one of the big contributors to growing out-of-pocket costs as mothers work more and use more child care.

So Labor’s policy is broader, with all families who use child care standing to gain, regardless of the number of children, their age and the family income.

It would cost about $2 billion per year – roughly three times more than the Coalition’s. But it would also have bigger benefits, sharpening workforce incentives for a much wider group of families.

The boost to GDP from higher workforce participation is likely to also be about three times bigger.

In terms of the impact on family budgets, the big difference between the policies is the number of children aged under six in care.

Families with only one child under six in care (or only older children in after-school care) would be unambiguously better off under the Labor policy.

For families with two children under six in care, there is little difference at most family income levels. For families with three children under six in care (probably less than 20,000 families at any given time), almost all would be better off under the Coalition policy.

A step forward, but not a game-changer

Overall, the Coalition’s policy is a helpful and well-targeted package that tackles some of the worst out-of-pocket costs and workforce disincentives. It will mean a real improvement for up to 270,000 families.

What’s missing is support for all the other families using child care. Almost 1 million families now use child care, and many would like to work more if they could afford to do so.

A broader policy supporting more families would have much larger and more widespread economic benefits. Of course, it would cost more too, but our research shows such an investment can be expected to deliver a boost to GDP of at least twice the cost.

This is a step in the right direction, but much more needs to be done to create a system that truly supports women’s workforce participation and long-term economic security.![]()

Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute; Kate Griffiths, Fellow, Grattan Institute, and Owain Emslie, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.