27 Nov TikTok has a startling amount of sexual content

And it’s way too easy for children to access, report Sonja Petrovic and Milovan Savic

Explicit content has long been a feature of the internet and social media, and young people’s exposure to it has been a persistent concern.

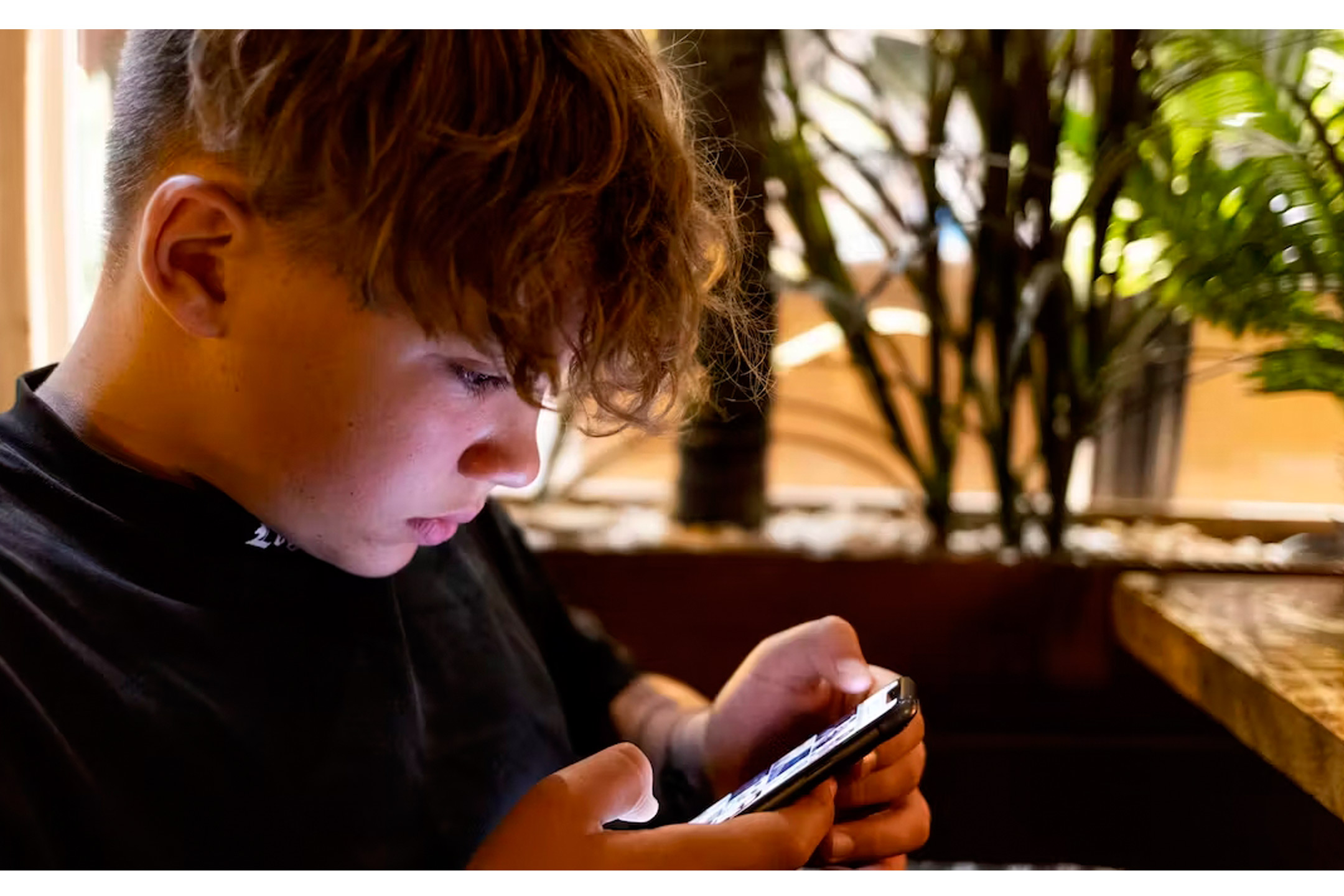

This issue has taken centre stage again with the meteoric rise of TikTok. Despite efforts to moderate content, it seems TikTok’s primary focus remains on maximising user engagement and traffic, rather than creating a safe environment for users.

As the top social media app used by teens, the presence of explicit content on TikTok can put young users in harm’s way. And while TikTok and regulators scramble to catch up with moderation needs, it’s ultimately up to parents and users to navigate these harms online.

TikTok’s content moderation maze

TikTok relies on both automated and human moderation to identify and remove content violating its community guidelines. This includes nudity, pornography, sexually explicit content, non-consensual sexual acts, the sharing of non-consensual intimate imagery and sexual solicitation. TikTok’s community guidelines say:

We do not allow seductive performances or allusions to sexual activity by young people, or the use of sexually explicit narratives by anyone.

However, Tiktok’s automated moderation system isn’t always precise. This means beneficial material such as LGBTQ+ content and healthy sex education content may be incorrectly removed while explicit, harmful content slips through the cracks.

Although TikTok has a human review process to compensate for algorithmic shortcomings, this is slow and time-consuming, which causes delays. Young people may be exposed to explicit and harmful content before it is removed.

Content moderation is further complicated by user tactics such as “algospeak”, which is used to avoid triggering algorithmic filters put in place to detect inappropriate content. In this case, algospeak may involve using internet slang, codes, euphemisms or emojis to replace words and phrases commonly associated with explicit content.

Many users also resort to algospeak because they feel TikTok’s algorithmic moderation is biased and unfair to marginalised communities. Users have reported on a double standard, wherein TikTok has suppressed educational content related to the LGBTQ+ community, while allowing harmful content to remain visible.

Harmful content slips through the cracks

TikTok’s guidelines on sexually explicit stories and sexualised posing are ambiguous. And its age-verification process relies on self-reported age, which users can easily bypass.

Many TikTok creators, including creators of pornography, use the platform to promote themselves and their content on other platforms such as PornHub or OnlyFans. For example, creator @jennyxrated posts suggestive and hypersexual content. She calls herself a “daddy’s girl” and presents as younger than she is.

Such content is popular on TikTok. It promotes unhealthy attitudes to sex and consent and perpetuates harmful gender stereotypes, such as suggesting women should be submissive to men.

Young boys struggling with mental health issues and loneliness are particularly vulnerable to “incel” rhetoric and misogynistic views amplified through TikTok. Controversial figures such as Andrew Tate and Russell Hartley continue to be promoted by algorithms, driving traffic and supporting TikTok’s commercial interests.

According to Business Insider, videos featuring Tate had been viewed more than 13 billion times as of August 2022. This content continues to circulate even though Tate has been banned.

Self-proclaimed men’s rights advocates centre their content on anti-feminist discourse, hyper-masculinity and hierarchical gender roles. What may seem like memes and “entertainment” can desensitise young boys to rape culture, domestic violence and toxic masculinity.

TikTok’s promotion of idealistic and sexualised content is also harmful for the self-perception of young women and queer youth. This content portrays unrealistic body standards, which leads to comparison, increased body dissatisfaction and a higher risk of developing eating disorders.

Empowering sex education

Due to its popularity, TikTok offers a unique opportunity to help spread educational content about sex. Doctors and gynaecologists use hashtags such as #obgyn to share content about sexual health, including topics such as consent, contraception and stigmas around sex.

Dr Ali, for instance, educates young women about periods and birth control, and is an advocate for women of colour. Sriha Srinivasan promotes sex education for high-school students and discusses sex myths, consent, STIs, periods and reproductive justice.

Milly Evans is a queer, non-binary, autistic sex-ed content creator who uses TikTok to advocate for inclusive sex education. They cover topics such as domestic abuse, consent in queer relationships, gender and sexual identities, body-safe sex toys and trans and non-binary rights.

These are just some examples of how TikTok can be a space for informative, inclusive and sex-positive content. However, such content may not receive the same engagement as more lewd and attention-grabbing videos since, like most social media apps, TikTok is optimised for engagement.

A bird’s eye view

Social media platforms face significant challenges in moderating harmful content effectively. Relying on platforms to self-regulate isn’t enough, so regulatory bodies need to step in.

Australia’s eSafety Commissioner has taken an active role by providing guidelines and resources for parents and users, and by pressuring platforms such as TikTok to remove harmful content. They’re also leading the way in addressing AI-generated child sex abuse material on social media.

When it comes to TikTok, our efforts should be poured into equipping young users with media literacy skills that can help keep them safe.

For children under 13, it’s up to parents to decide whether they allow access. It’s worth noting TikTok itself has an age limit of 13 years, and Common Sense Media doesn’t encourage use by children under 15. If parents do decide to allow access for a child under 13, they should actively monitor the child’s activity.

While restricting apps’ use might seem like a quick fix, our research has found social media restrictions can strain parent-child relationships. Parents are better off taking proactive steps such as having open discussions, building trust, and educating themselves and their children about online risk.

The Conversation reached out to TikTok for comment but did not receive a response before the deadline.![]()

Sonja Petrovic, Assistant Lecturer in Media and Communications, The University of Melbourne and Milovan Savic, Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society, Swinburne University of Technology

Main Image: Getty Images

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.