24 Apr Too many Aussies are starting a family and raising their kids in poverty

New research by Dr Ana Gamarra Rondinel and Dr Anna MH Price finds that the birth of a first child reduces household income and increases the risk of disadvantage

In fact, at least one in three families with children experience deprivation, missing out on essential items like food, stable housing and healthcare. And this is something that’s more pronounced for families with children under five years of age.

Even by the time Australian children start school, developmental inequities are evident. stemming from adverse social conditions – like poverty.

Children living in Australian suburbs experiencing the most disadvantage have three times the developmental vulnerability of those living in the most advantaged (19 per cent versus seven per cent).

Our research – the result of a partnership between the Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research and the Centre for Community Child Health at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute – has found that the arrival of the first child reduces household income and increases the probability of poverty.

The cost of a first child

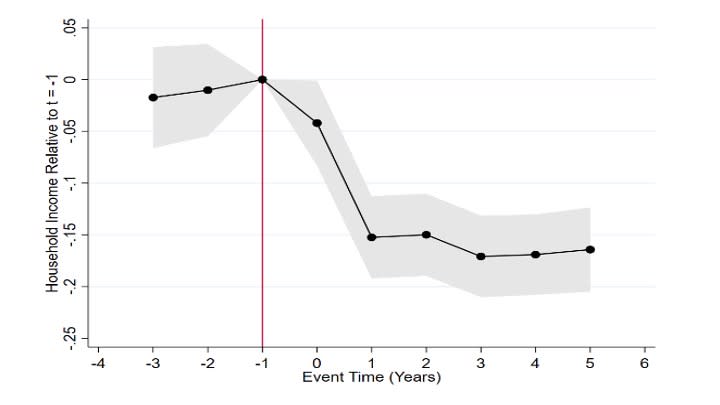

The arrival of the first child reduces household income between 16-18 per cent on average.

This drop is higher for one-parent households (23-27 per cent) than for two-parent households.

Five years after the birth of a first child, household income has not returned to its original level, stabilising at around 18.3 per cent below the pre-childbirth income.

The reduction in a woman’s hours of work, employment and hourly wages following the arrival of children explains much of this drop.

Australia’s motherhood penalty – the severe wage and hiring disadvantages that mothers face in the workplace – is one of the highest among high-income countries. This is due in part to the relatively conservative norms experienced by Australian men and women compared to other countries.

Other factors – like job loss, separation and more children – may contribute to the lack of recovery, even five years after the birth of a first child.

The difference between one and two-parent households

The change in household income at childbirth relates to poverty.

We found that 37 to 40 per cent of households stayed or moved into or near poverty in each of the five years following the arrival of their first newborn.

Movement between poverty categories was substantially greater for one-parent than two-parent households.

For one-parent households, 23-32 per cent remained out of poverty, four to six per cent moved out of poverty or near poverty, and 63-70 per cent stayed in or moved into poverty or near poverty.

If we look at two-parent households, 61-64 per cent remained out of poverty, two to four per cent moved out of poverty or near poverty, and 34-36 per cent stayed in or moved into poverty or near poverty.

We also found the probability of poverty for new parents is, on average, 12 per cent for all households, 17 per cent for one-parent households and 10 per cent for two-parent households

For one-parent households, the absence of partner earnings contributes to a higher poverty risk than for two-parent households.

Government protection from poverty

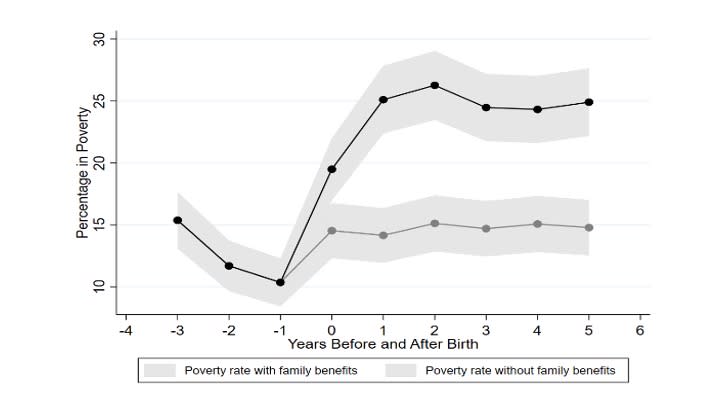

So, do the Australian government’s family payments help mitigate poverty around the birth of a first child?

The short answer is yes. Without family payments, the average poverty rate increases from 26 per cent for one-parent households and 10 per cent for two-parent households before childbirth to 63 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively, in the following years.

With family payments, the average poverty rates after childbirth are 37 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively.

While family payments do help reduce poverty among households with a first baby, these payments do not protect them from falling into poverty.

Even with family payments, a substantial number of Australian families are starting a family and raising their children in poverty.

A buffer against poverty

In Australia, there is increasing interest in equitable policy and support for low-income families. This can be seen in the national well-being budget and increases in childcare subsidies and minimum wage.

The importance of early childhood and support for parents is also gaining prominence through the National Action Plan for the Health of Children and Young People 2020-2030, the proposed Early Years Strategy, and the Plan for Affordable Child Care.

But how well are these policies buffering families from the risk of poverty? And given Australia’s increasing inflation and cost of living, is there a case for investing more heavily during early childhood?

Although poverty is defined by household income, actions to halve or even eradicate child poverty are more complex than increasing household income alone.

Addressing child poverty requires a more comprehensive approach, a rigorous understanding of the extent of the problem and identification of points for change.

Our analysis is a necessary step in understanding why so many Australian families are raising their young children in poverty – and the steps we can take as a nation to prevent it.

Dr Ana Gamarra Rondinel, University of Melbourne and Dr Anna MH Price, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and University of Melbourne

See also: Women are doing too much, and it’s hurting their mental health

Main Image: Getty Images

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article