11 Sep Why are one in three Australian e-scooter fatalities children?

A new study based on media reports finds young Australian e-scooter riders are much more likely than adults to die in crashes on our roads. Milad Haghani asks, are our kids disproportionately at risk while riding them?

Recently, I’ve repeatedly come across tragic news reports of children killed in electric scooter, or e-scooter, crashes.

In Australia, we don’t currently have a process of recording these deaths, unlike other modes of transport where death and injury statistics go directly into the national databases.

However, knowing the risks that e-scooters pose to our children is important.

I decided to take matters into my own hands and generate a dataset (as comprehensively as possible) to answer two simple questions: what percentage of e-scooter-related deaths are children? Are our kids disproportionately at risk while riding them?

The answers shocked me.

Building a dataset from scratch

To create this dataset, I had to scour local Australian news coverage.

Deaths related to e-scooters in Australia are relatively rare and, usually, when they do occur, the story is covered by at least one local outlet. So, I did several deep dives into those news stories for the period of 1 January 2020 to 1 July 2025.

While I cannot guarantee that this data is 100 per cent comprehensive, I believe it’s now sufficient to answer those key questions.

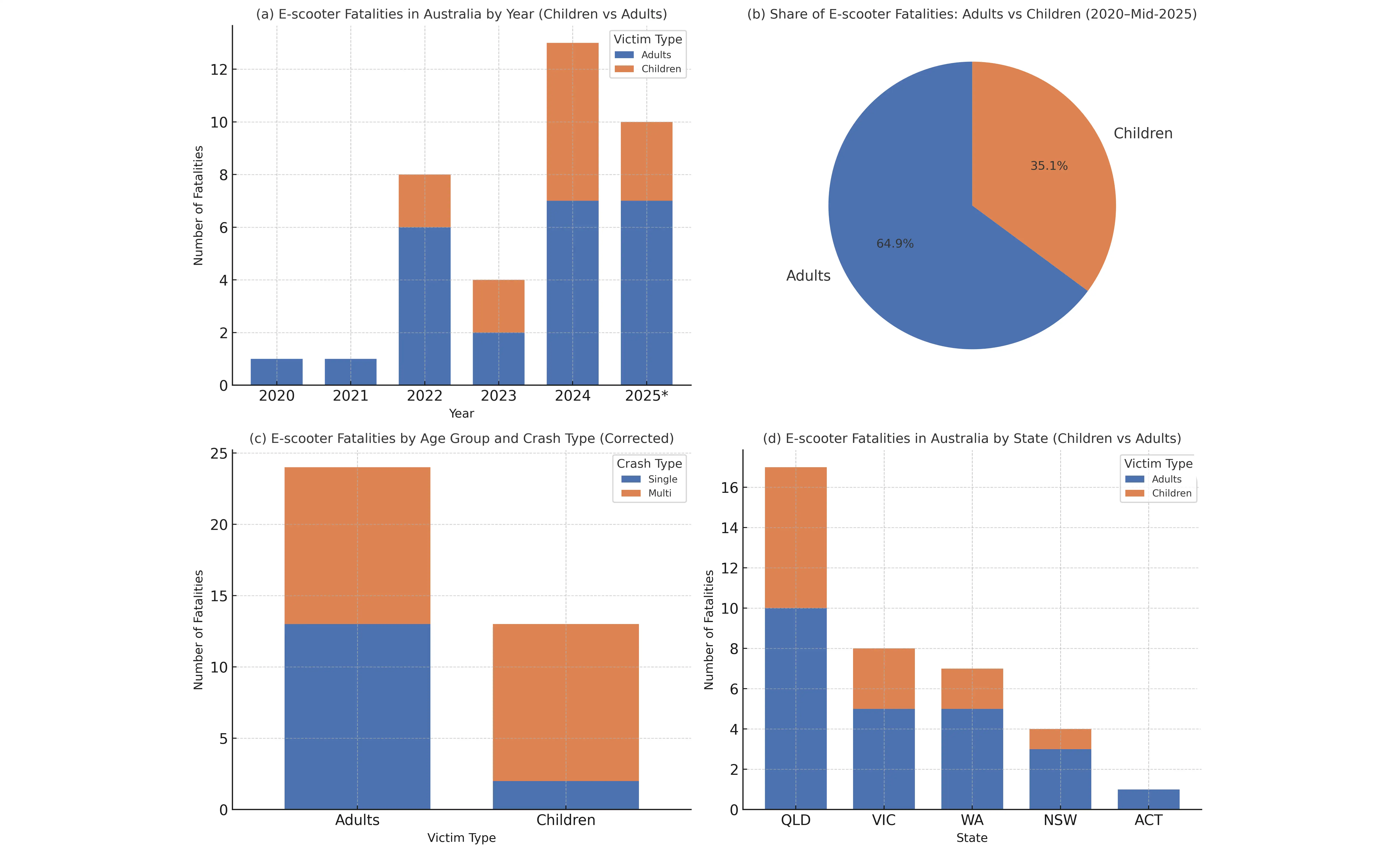

Through this process, I identified 37 fatal e-scooter incidents across Australia for this period.

But 13 of these deaths – that’s more than one in three – involved children under 18.

That is an alarming over-representation.

We don’t have the data on the age or kilometres travelled to understand how over-represented children might be in fatalities fully, but given that a) e-scooters are illegal for children under 16 in most states and territories, b) most e-scooter hire companies don’t allow children to rent and c) observationally, the majority or riders I see day-to-day are adults, one-third appears to be a vast over-representation.

So, this is a clear cause for concern.

Kids are vulnerable

Some of the patterns I found were expected.

For example, nearly half of all fatal crashes (46 per cent) occurred in Queensland. Not surprising given the state’s early and widespread adoption of e-scooters, both privately owned and shared.

There’s also a clear upward trend in fatalities over time.

In 2020 and 2021, there were just one or two recorded deaths each year. But by 2024, that number had climbed to 13. And in the first half of 2025 alone, there have already been ten confirmed fatalities – three of them children.

But some other patterns are more revealing.

The vast majority of the fatal crashes involving children (11 out of 13, to be exact) were collisions with another vehicle, including cars, trucks and utes.

In contrast, more than half of the crashes involving adults (13 out of 24) were single-vehicle incidents. These are typically cases where the rider loses control, crashes into a fixed object or falls off without the involvement of any other vehicle.

I should highlight that this is exclusive to fatal crashes only. As I was undertaking this research, a parallel investigation was underway in Queensland, where medical doctors audited paediatric e-scooter trauma in a regional Queensland hospital.

These were non-fatal crashes involving children, predominantly resulting from falls.

A child’s risk of death when riding an e-scooter is more about their vulnerability in environments they share with larger, faster vehicles.

But the vast majority of nonfatal injuries happen as a result of falls and don’t involve any other vehicle.

A clear overexposure to risk

To compare injury rates and injury severity between adults and children would need its own dataset – something that’s far more difficult to pull together than fatality reports.

But in the absence of a robust national database, we can still draw on published evidence, both locally and internationally.

For example, last year, the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network warned of a sharp rise in serious injuries resulting from e-scooters and e-bikes. This included multiple cases of head trauma, internal injuries and fractures in children under 16.

However, this data doesn’t provide a direct comparison with the rates of injury in adult riders.

International studies, however, do give us some perspective.

An Austrian study of more than 600 children who sustained scooter injuries found that teenagers riding e-scooters were significantly more likely to be involved in potentially life-threatening traffic accidents than those riding non-electric scooters.

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) reported that children under 15 account for 36 per cent of micromobility injuries, despite representing just 18 per cent of the US population – basically double their proportion.

This suggests a clear overexposure to risk among younger riders and is largely consistent with our local observation of fatalities.

A lack of experience and hazard awareness

There are several simple explanations for why children may be more vulnerable on e-scooters.

Younger riders generally have poorer hazard perception and less experience navigating roads.

They’re also physically smaller, which makes them more challenging for drivers to see, especially in busy environments.

Many e-scooters can reach speeds of 25 kilometres per hour or more, which is fast enough to cause serious harm, particularly if you’re a child sharing space with vehicles. And while helmet use is compulsory in Australia, it can be patchy at best among kids.

Regulation is not enough

E-scooter regulation varies significantly from state to state, and it’s constantly changing.

In most jurisdictions, the minimum legal riding age is 16; however, Queensland, for example, allows riders aged 12 and above with supervision.

In New South Wales, privately owned e-scooters are not permitted on public roads or footpaths at all, while South Australia is in the process of legalising them in public spaces.

If we look at shared e-scooters, companies usually set their own minimum age depending on the provider and the city, but this is not always necessarily consistent with the local regulations.

And despite all the regulations, enforcement is inconsistent. In practice, what this means is that it often comes down to parental decisions.

The private e-scooter market has long been happy to market these devices directly to children, with flashy designs, bright colours and easy online purchase. The rules say one thing, and the marketing says something else.

But the data is clear.

The majority of child e-scooter deaths in Australia occurred in collisions with larger vehicles. That’s where the risk is – not the backyard or the footpath – but public roads shared with traffic.

Children should not be riding e-scooters there.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not trying to be a safety alarmist. No mode of transport is risk-free. The only way to eliminate all transport-related injuries would be to cancel transport altogether.

But we don’t do that, because getting from A to B has value. Society accepts some risk in return for that value, and we try to manage the risk as best we can.

However, this is about determining what constitutes an acceptable risk and what constitutes an unacceptable one.

When it comes to children on e-scooters, the data indicate that this falls into the second category – the risk is too high for far too little benefit.

Associate Professor Milad Haghani is from the University of Melbourne