04 Dec Remaking The Grade: The School Report

Current approaches to assessing and reporting what a student is learning may not be the best way to represent individual progress in school reports, writes Geoff Masters.

A child whose learning is lagging behind that of other children can be judged to be ‘failing’, even though they are making excellent learning progress.

Can school reports send unintended messages and have unanticipated consequences?

A milestone in most children’s lives is their first school report. It is the first formal piece of communication from the school about how well a child is settling in and what progress they are making. I still have my own school reports, and I’ve kept my children’s too – stashed away with other childhood keepsakes.

But just how dependable are the reports that schools send home? Do they provide accurate descriptions of a child’s school experience and learning? What impact do they have on children themselves? Can school reports send unintended messages and have unanticipated consequences?

In recent years, concerns have been expressed regarding the widespread use of A to E grades

Different methods of reporting to parents are used in different Australian States and Territories, and in different years of school. Among the methods used are A to E grades, performance bands, standards such as ‘very high achievement’ to ‘very limited achievement’, marks out of 50, and marks out of 100.

As Australia moves towards a national curriculum, discussions about the best ways to report children’s school achievements will continue. In recent years, concerns have been expressed that the widespread use of A to E grades, and some other approaches to assessing and reporting what is learned in schools, may not be consistent with what we are learning about learning itself. Opponents of A to E report cards argue that they can reinforce children’s negative views of their own ability to learn and are usually not very helpful in illustrating a child’s progress over time.

Whatever form a school report takes, it is important to recognise that children begin school at very different levels of social, emotional, cognitive and language development. Children will also continue to have very different levels of development and learning throughout their time at school. For example, in each year of primary school, the most advanced 10 per cent of children have reading and mathematics levels several years ahead of the least advanced 10 per cent of children. This observation is probably not new or a cause for concern: children have always developed and learned on different timelines.

What is new, is evidence that the human brain is able to keep building new pathways and new brain cells throughout a person’s life. In other words, it is never too late to learn. Even when areas of a brain are damaged, other areas often can learn to take over those functions. This means that there is usually no deadline for learning. The fact that a child has not yet learned something does not mean that they cannot learn it in the future.

What one child can learn, almost all children can – if they are motivated

Research in classrooms is leading to much the same conclusion. What one child can learn, almost all children can learn if they are motivated and prepared to make an effort. They also need to be given the time and learning experiences matched to their readiness and individual learning needs. Schools increasingly see every child as being on a ‘path of learning’. Children are recognised as being at different stages in their learning and to be progressing at different rates, but all children are now considered capable of further learning if appropriately supported. This is a much more positive and optimistic view of learning than earlier beliefs that children differed markedly in their capacity to learn.

Still other research is showing how important it is that children have confidence in their ability to learn. Some children, especially in Western countries like Australia, tend to have what researchers call ‘fixed’ beliefs about their learning ability. These children often believe that success at school depends on ‘ability’, and that people have ability in different amounts. If a child becomes convinced that they lack ability, then they often conclude that effort won’t make a difference. In contrast, children in East Asian countries tend to have ‘incremental’ beliefs about ability. They are more likely to believe that a person can become ‘smart’ through hard work and persistence.

Still other research is showing how important it is that children have confidence in their ability to learn. Some children, especially in Western countries like Australia, tend to have what researchers call ‘fixed’ beliefs about their learning ability. These children often believe that success at school depends on ‘ability’, and that people have ability in different amounts. If a child becomes convinced that they lack ability, then they often conclude that effort won’t make a difference. In contrast, children in East Asian countries tend to have ‘incremental’ beliefs about ability. They are more likely to believe that a person can become ‘smart’ through hard work and persistence.

What happens in schools is not always consistent with what we now know about learning itself.

When I went to school, my teachers organised classroom seating on the basis of our test results. The child who came first in the most recent test was seated in the back left corner of the room, the child who came last, in the front right corner, and everybody else was seated in between according to their test score. In this way, learning at school was turned into a competition. There were winners at the back of the room and losers at the front. Of course, as children we were already well aware of how different we were. But this emphasis on comparison and competition undermined important messages my school could have been delivering: that it is okay for children to be at different stages in their learning and development. In fact, there is every reason to expect them to be – and that all children are capable of making good progress in their learning regardless of their current levels of achievement.

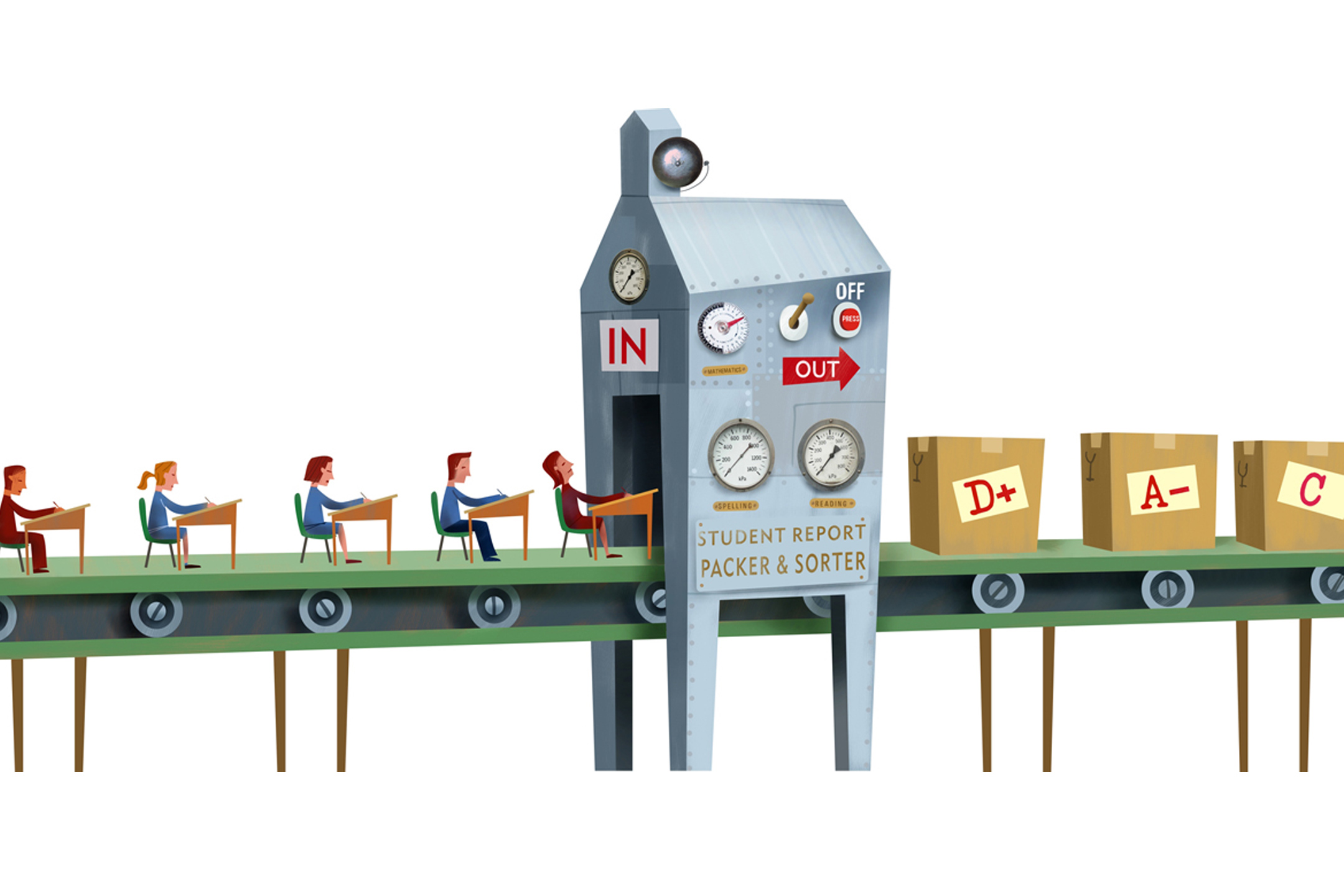

Thankfully, we no longer arrange classrooms in this way. But we do organise schools on what Linda Darling-Hammond from Stanford University refers to as a “factory assembly line model of schooling”. Darling-Hammond describes children as moving through school along a “conveyor belt” from the first year of primary to Year 12. We group children into classes on the basis of their age, and then design and deliver school curricula for each of these age/year groups. In doing this, we make the assumption that children of the same age are more or less equally ready for the same curriculum. But, as already noted, some children in today’s classrooms can be several years ahead of other children in the same room.

The grouping of children in this way makes it possible to set expectations for children’s learning based on their age/year level. These expectations are sometimes referred to as ‘achievement standards’. Teachers then make a judgement about whether a child has met the achievement standard for their year or has failed to meet it. In this way, the notion of ‘failure’ sneaks into schooling. A child whose learning is lagging behind that of other children can be judged to be ‘failing’, even though they are making excellent learning progress. School reports that focus only on the attainment of year-level expectations and that do not report individual progress can send the false message that a child is failing as a learner.

An alternative to reporting passing and failing judgements is to ‘grade’ how well each child has performed on the curriculum for their year.

Again, grades are widely used to indicate the quality of production-line output (high-grade, premium-grade, A-grade and so on). In schools, A to E grades are attractive because they have a long history and are familiar. We think we know what they mean, which in general we don’t. One teacher’s A can be another teacher’s B.

A disadvantage of grades is that they are not useful in showing a child’s progress over time. A child who receives a ‘D’ in mathematics this year, a ‘D’ next year, and a ‘D’ the year after, may appear to be making no progress in mathematics at all. An analogy would be reporting a child’s height as ‘C’ year after year based on their height in relation to other children of the same age. Worse, a child who receives a ‘D’ year after year may conclude that there’s something stable about their ability to learn; that they are a ‘D’ student.

One way to build a child’s confidence in their ability to learn is to help them see the progress they are making over time. Parents and teachers can do this by keeping samples of a child’s past work such as their drawing and writing or recordings of their reading. School reports can do this by showing the progress a child is making – not only during one year of school, but across the years of school.

For example, the Nationally-introduced literacy and numeracy tests (NAPLAN) are designed to help teachers, parents and children see individual progress across the years of school. Each child’s reading, writing and numeracy skills will be measured in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 and reported on a scale that will allow literacy and numeracy growth over time to be monitored, much as a child’s physical growth can be monitored.

Efforts are underway to develop still more effective ways of reporting children’s school learning in the future.

Exactly what form school reports of the future will take is not clear, but some desirable features of these reports are taking shape. First, they must be consistent with what we are learning about learning. They should reflect an understanding that every child is on a path of learning and is capable of further progress with effort and appropriate support, and that children are at different stages in their learning and make progress at different rates. This means that the focus of school reports should be on establishing and reporting where individuals are up to in their learning and on identifying how parents can assist, rather than on making judgements and comparisons based on the performances of other children.

Second, school reports should build a child’s understanding that they are capable of successful learning by helping them to see the progress they make over time, and by helping them to understand the relationship between effort and progress. When reports show what progress a child is making, parents are better able to judge the adequacy of this progress.

Finally, school reports should not try to protect children from the reality of failure.

Schools have a role to play in building resilience and a healthy attitude to failure, which is essential to growth and presents a learning opportunity. Above all, children need to be encouraged to see failure as an event not a state: to develop a deep belief that, while they will experience failure from time to time, this does not change their remarkable capacity for ongoing successful learning.

Professor Geoff Masters AO is chief executive of the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER)

Illustrations by Gregory Baldwin