16 Mar How can you support an anxious child during NAPLAN testing?

From March 13, NAPLAN testing for 2024 will begin, writes Rachel Leslie. Over the following two weeks, all Australian students in years 3,5,7 and 9 are expected to sit tests in literacy and numeracy.

Results are then aggregated for schools and other demographics and made public. Students also get their individual results.

For students in Year 3, this will be their first experience of a formal test. For others, they will be sitting the test among school and media hype about the “importance of NAPLAN”.

The NAPLAN debate

Since it was introduced in 2008, NAPLAN has polarised the community. Some education experts see it as counterproductive (with too much emphasis on test performance rather than learning). Others emphasise the importance of the data collected, and how this informs teaching practice and school funding.

One of the prevailing concerns relates to the impact on student wellbeing.

While many students do not feel any anxiety, one 2022 study of more than 200 high school students found 48% felt worried about what the test would be like and how they would perform. A 2017 study of more than 100 primary students revealed up to 20% of children had a physical response to the test, such as feeling sick, not sleeping well, headaches or crying.

For parents, the stress and anxiety their child experiences in the lead up to NAPLAN can cause them to worry and even withdraw their child from the assessment.

But test anxiety is not inevitable. Here are some simple things parents and teachers can do to support students, not just for this assessment, but into the future.

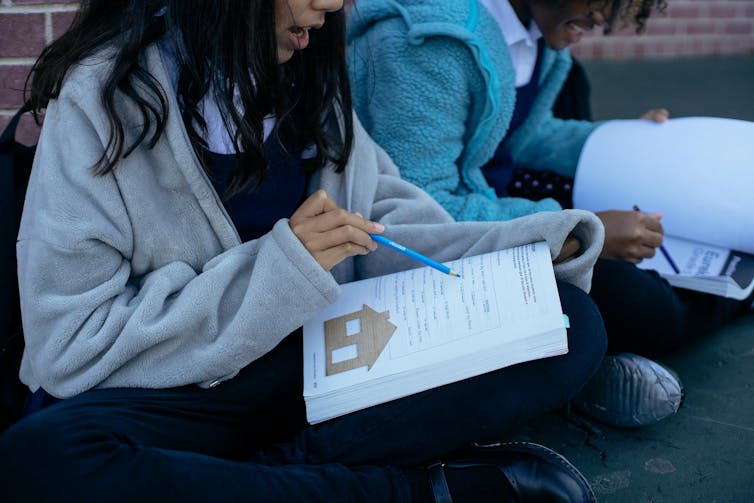

Mary Taylor/ Pexels, CC BY

1. Talk about the purpose of the test

NAPLAN is not just about individual student results and whether you are a “good” at maths or “bad” at reading. It’s about informing teaching and learning.

The results help teachers do their jobs by identifying areas of reading, writing and maths that need more attention. This can help individual students, classes or entire schools.

When the results are collected at state and national levels, they also help tell governments where to put more efforts and funding to help support students.

2. Talk about how the test is a journey (not a destination)

Children learn from experience. This enables them to predict what might happen in similar future events.

Talk about NAPLAN as “practice” for future tests. So if you sit NAPLAN test in your younger school years this will help you handle other tests in senior school or maybe even university.

Emphasise that sitting the test is not about a particular outcome or result. It’s about embarking on an experience and learning what it is like to do a standardised tests. In this way, NAPLAN can help students build resilience.

3. Teach your child to manage anxiety

Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be successful in addressing anxiety symptoms in children.

Mindfulness can teach children to recognise anxiety symptoms such as a fast heart beat, shortness of breath or racing thoughts. By encouraging children to focus on the present moment, mindfulness can help children through improved concentration, better emotional regulation and fostering a sense of calm.

Smiling Mind is an Australian app designed to teach children to be mindful in a developmentally appropriate and guided way. The app is free to download and use. You could sit or lie down with your child and do a “body scan” (where you scan your entire body and notice how it feels) or a listening practice (where you pay attention to the sounds around you).

If your child is experiencing significant test anxiety, such as headaches, tummy pains or a racing heart, there may be more to it than just concerns about NAPLAN. For children aged 12–18, Headspace – Australia’s mental health foundation for young people – offers a range of services.

For younger children, or if you are still concerned, speak to your child’s teacher, the school counsellor or your GP.![]()

Rachel Leslie, Lecturer in Curriculum and Pedagogy with a focus on Educational Psychology, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.