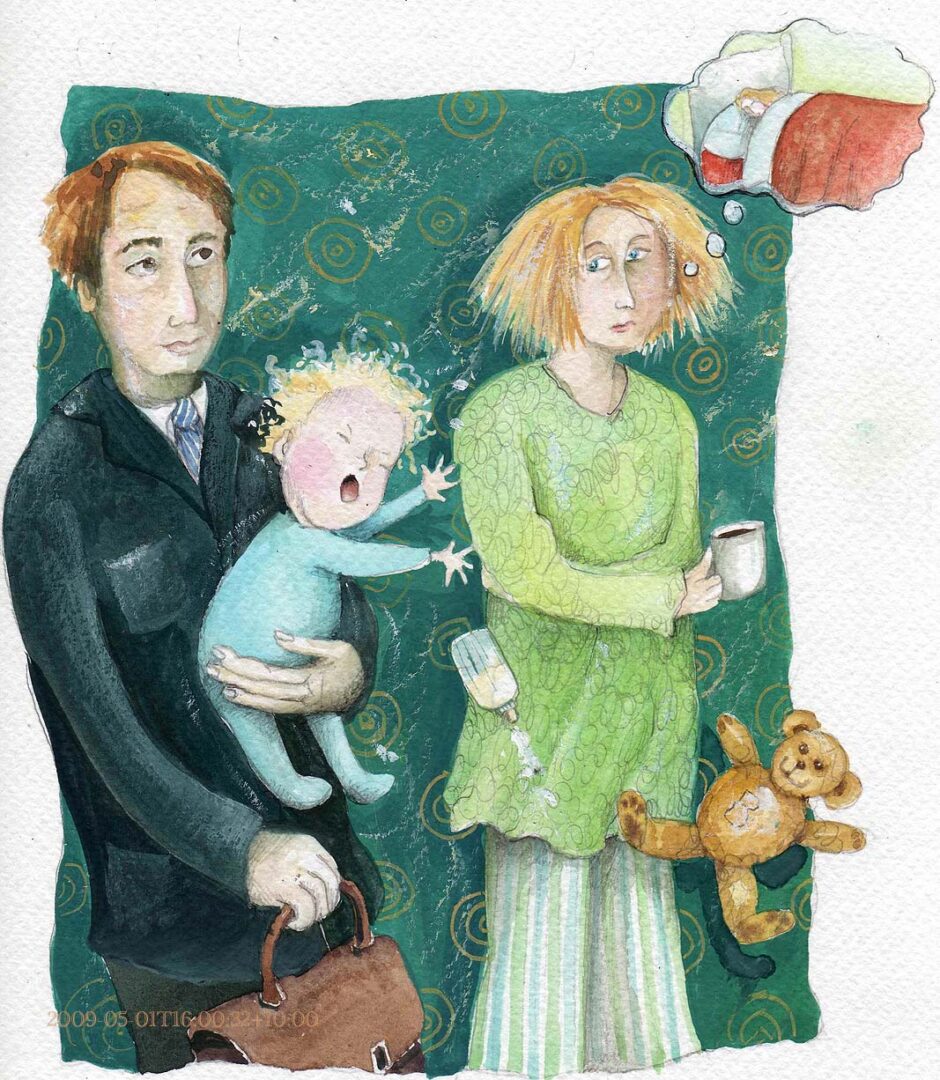

12 Sep From Partners To Parents

Susan White writes about the strain having kids can place upon relationships.

James and Anna have been together for eight years. For six years, they both had successful careers in business and travelled overseas at least annually. Two years ago, Anna decided she wanted a child. James wasn’t sure, but after realising he might lose Anna if he didn’t agree, he came around. Now, little Jasmine is six months old, and she’s a beautiful baby with warm brown eyes and two new teeth. James and Anna adore her.

But James and Anna are having trouble. Anna feels perpetually annoyed with James. “He doesn’t have the first clue about what my life is like now. He goes off to work, and I am left with a screaming baby. Then he comes home and wonders why I am exhausted. He thinks I have been off having lattes all day. The last straw is that when we go to bed, he wants sex! He’s got no idea.”

James doesn’t think there is a problem. “I reckon all couples have a bit of a rough time when a baby arrives. I wish she would smile sometimes, though.”

Research into the effect of children on relationships shows that relationship satisfaction takes a dive when you have kids, and the sad truth is that it doesn’t pick up again until the kids leave home. As much as most parents adore their children and wouldn’t have life any other way, having kids strains parental relationships – sometimes to breaking point.

Why is it so hard? There are the obvious biological factors: sleep deprivation, the changes in hormones Anna has experienced since giving birth, plus the physical changes to her body, and the lack of time James and Anna have together, just the two of them. These factors lay the groundwork for a challenging time but are only half of the story. There is also the psychological impact of the new roles of parenting, the loss of Anna’s career and the changed dynamics of a couple transforming into a family.

Dr Ingrid Sturmey, counselling practice leader and, counsellor and relationship educator, thinks that the choices we now have in life contribute to a couple’s struggle over the transition to parenthood. “The form relationships take now is quite different. Whereas in the past, it was just marriage, now you have de facto relationships, marriages where people live apart, gay relationships, and people having children outside of a committed relationship. And there are different ideas of commitment now, so couples need to negotiate what they are committed to. A couple might be committed to the idea of each other following the individual paths of their careers, but not to the idea of having children.”

Sturmey sees a downside to all these choices. “People often set up relationships as leisure-time companions, where they have fun together and have sex. They don’t necessarily do it with the idea of becoming a family, whereas in the past, people mostly didn’t have sex until they got married, and they would choose a partner who would be a good parent.”

Sturmey sees a downside to all these choices. “People often set up relationships as leisure-time companions, where they have fun together and have sex. They don’t necessarily do it with the idea of becoming a family, whereas in the past, people mostly didn’t have sex until they got married, and they would choose a partner who would be a good parent.”

Like James and Anna, many couples reach the seven to eight-year mark of having fun, travelling, and working on their separate careers, and then the woman feels ready to start a family, and the man is not sure. “The relationship gets stressed because you have to choose the next stage, whereas in the past, you didn’t have to choose.” Then, it becomes about competing priorities.

Couples don’t want to lose their freedom, and tension stems from how they are going to manage to keep up their lifestyle, with everyone trying to optimise all aspects of their life: career, family, and their own interests. And in most people’s lives, it doesn’t all fit; something has to give. Sacrificing desired elements of our lives breeds resentment, especially if we perceive that we have sacrificed more than our partner.

Sturmey says, “When children come along, it’s almost like couples who are used to getting on together as companion-lovers or emotional-sexual friends are suddenly transformed into parents with the idea that they are responsible for raising a generation. Now that raises questions: ‘Who is going to be responsible? Who is going to look after the child, and who is going to continue the lifestyle they want?’ Because it might work fine to say, ‘We don’t follow traditional roles’ when there are just two of you, and you head off for a ski weekend, and both pack, and both cook a later dinner when you get home or get takeaway. But when it comes to who gets up at night for the baby, to breastfeeding, and who is going to give up their career moving forward, then the model where neither member of the couple plays a traditional role doesn’t work.

Mostly, the woman has to go back into a dependent role and lose her professional edge. Mostly, she withdraws to some degree from her career and her life as it was. As she copes with this – even if she loves having children – she has to change profoundly, and some of her values and choices might have to change.”

Maternal and child-health nurse Jeandanielle Evans agrees. “The transition to parenthood has really changed over the past 10 years. The average age of a first-time mum is now 30, and they come to motherhood having had a career, responsibilities and their own money. Most families have had two wages. Then, when they suddenly have this little bundle that they have dreamt about forever, everything changes: they are suddenly down to one wage, and the mum has a huge transition to motherhood because although she loves being a mother, society doesn’t see being a mother as highly valuable or any great skill. So she has this massive transition to ‘Is this who I am now? Is this what my life is?’

So what can Anna and James do? How do they avoid becoming part of the divorce statistics?

Evans thinks the key is working hard at communication. “I always challenge couples to have 10 minutes per day where they check in with each other as adult individuals and as an adult couple. At that time, they are not allowed to talk about the baby. I am trying to get them to talk about what is going on for them physically, practically, and emotionally to check in with each other. Before children, most couples would have checked in with each other at the end of the day: ‘How was your day? How was work, how are we as a couple?’ Then, when the baby arrives, it’s all about ‘How many feeds did the baby have, how many poos and wees, were they settled?’ Everyone’s attention is on the baby.”

Evans thinks the key is working hard at communication. “I always challenge couples to have 10 minutes per day where they check in with each other as adult individuals and as an adult couple. At that time, they are not allowed to talk about the baby. I am trying to get them to talk about what is going on for them physically, practically, and emotionally to check in with each other. Before children, most couples would have checked in with each other at the end of the day: ‘How was your day? How was work, how are we as a couple?’ Then, when the baby arrives, it’s all about ‘How many feeds did the baby have, how many poos and wees, were they settled?’ Everyone’s attention is on the baby.”

Sturmey advises couples who are considering starting a family to talk it through first. “In a way, this is harder for women than men because often women so desperately want to have children they think, ‘I will manage somehow,’ whether there is a partner to bring around to the idea or whether the woman decides to do it on her own. It is important to think through the implications for children. How are we going to face this? How are we going to make sure we remain really positive and work through things with each other as they come up?”

One key strategy is for parents to understand how they deal with stress and fatigue. Sturmey encourages couples to ask for what they need, as their partner might not know intuitively what they want. “I suggest not to focus too much on asking for chores to be done because I think mothers often say ‘, if you feed the baby or do the vacuuming, I will feel better’ when actually what they need is to feel close to their partner. They need to talk over how they feel, have someone to listen to how yucky they feel, someone who won’t just try and fix it, who won’t close off and won’t worry, someone who will give them a cuddle and comfort them and give them the message, ‘I’m here too, we’re both in this’.”

Implicit in this suggestion is that each person tries to understand their partner’s needs when they are stressed. “There is an idea that as well as a ‘fright and flight’ response to stress, women have a nurturing ‘tend and befriend’ response. When they are stressed, they nurture and care for each other, and they often want to be looked after in that way when they are stressed.” The stereotypical male response of Mr Fix-it might help bring in the washing but might not help their partner’s stress as much as a hug.

Sturmey cautions against becoming contemptuous of your partner. “Never say stuff that is demeaning and puts them down. That includes anything that takes away from people’s feeling that they have a right to feel the way they do. If a person is not coping, they are not coping; whether another person, such as their mother-in-law, can cope or not is beside the point. Judging your partner’s reaction to being a parent will not help.”

Evans encourages parents to plan some time in their day just for father and child. “It has taken an equal part of both parents to create this child, so it is important for dads to bond independently with their children. Choose something they can do together, like bath-time or bedtime stories, but without the mother looking over the shoulder saying ‘You’re doing it all wrong!’”

Evans has some practical suggestions for mums at home with a baby. “If the baby regularly has two sleeps in a day, make one of those sleep times your time: sleep or read the paper or sit in the sun and relax. No housework allowed!” She also reminds mothers to have realistic expectations of themselves and their bodies. “If you’ve been up overnight with the baby, try to make up the sleep the next day.” She also encourages new mums and dads to talk with other parents. “When mums form mothers’ groups, I suggest they get the dads together too because often dads don’t talk with other new dads much. Men need to talk too about the time they are having, but they often don’t seek that out as much as women.”

Don’t believe anyone who tells you parenting is easy. And keeping a relationship healthy in the middle of it all is hard work. As Evans says, “One day, this little baby is going to grow up and leave home. And we want the parents to be able to look at the person in bed next to them and remember their name.” And, hopefully, to know and share their toils, troubles and dreams.

Illustrations by Penny Lovelock