08 Aug Thinking in Boxes

We’ve all heard of thinking outside of the box, writes author Jess Horn. But what if you thought in boxes?

Not literally, of course (although cats do make a good case for that)! But imagine your thoughts were organised in categories, and thinking about one category automatically excluded all others. This is the way of thinking that led me to my autism diagnosis at age 34.

Like many late-diagnosed women, I discovered I was Autistic after decades of feeling different and struggling with my mental health. I didn’t know why I clung to routine, rewatched movies until I memorised them, or had thousands of internalised rules nobody else seemed to follow. I didn’t know why everything seemed easier for other people until the answer revealed itself in my mid-thirties.

But what do boxes have to do with autism? Technically, nothing at all! But ‘thinking in boxes’ is an analogy to describe the exclusive associations my brain makes. As with many of my Autistic traits, I came to realise that thinking in boxes is not a universal experience. That’s not to say it’s a universally Autistic experience, either, because every Autistic person comes with a unique set of traits and experiences. But for me, thinking in boxes has a significant impact on the way I perceive the world.

Imagine this: Yesterday, we had a detailed conversation about fruit. Today, you say to me, ‘How’s that fruit going?’ To which I say, ‘What fruit? We’ve never spoken about fruit,’ and you look at me like I must have amnesia. But here’s what happened. While you thought we were talking about fruit, I know for a fact that yesterday, we were talking about pears. And today, what I heard you say was, ‘How are those apples going?’ And I’m unsure what I’m meant to know about apples because you’d only ever told me about pears. I didn’t know I was meant to apply the pear information to apples, because I had them in their respective boxes. You, on the other hand, shoved them all in a basket and called them fruit.

Imagine this: Yesterday, we had a detailed conversation about fruit. Today, you say to me, ‘How’s that fruit going?’ To which I say, ‘What fruit? We’ve never spoken about fruit,’ and you look at me like I must have amnesia. But here’s what happened. While you thought we were talking about fruit, I know for a fact that yesterday, we were talking about pears. And today, what I heard you say was, ‘How are those apples going?’ And I’m unsure what I’m meant to know about apples because you’d only ever told me about pears. I didn’t know I was meant to apply the pear information to apples, because I had them in their respective boxes. You, on the other hand, shoved them all in a basket and called them fruit.

‘So, why not just get a fruit basket?’ you may ask. To which, I’d suggest you try thinking in a foreign language for a day and see how you feel. It’s a skill I’d love to have, but I don’t, and I won’t, because I can’t. Thinking in boxes is my default language. It’s the way I retrieve memories, learn new information, and make sense of everything around me.

While this systematic thinking style has its perks, thinking in boxes doesn’t always do me favours. Especially when I’m working within a predominantly neurotypical framework. For example, recruiters in job interviews love to say things like, ‘Tell us about your (insert very broad skill descriptor here).’ I’ve found myself speechless in the face of these questions because the question didn’t give me a clue as to which box I should open.

Knowing I think like this doesn’t make it change, and nor should it need to. As a community, we must do better at valuing our differences and accommodating each other’s needs. The fact I can’t access the information required to answer a question is as much a problem with the question, as it is with my labelling system. But as a late-diagnosed Autistic, a valuable first step to support myself and model acceptance is to accommodate my own needs, too. This is where my debut picture book, Bernie Thinks in Boxes, comes in.

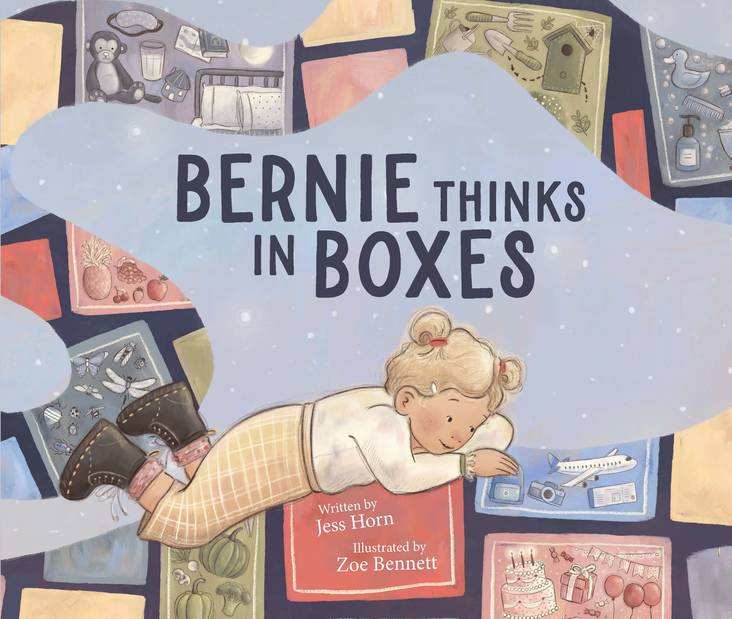

Bernie is a kid who, like me, thinks in boxes. She has boxes for everything: for home, for school, and even for the park. But one day, Bernie’s boxes collide, and she must find a way to make sense of her world again.

When I began writing about Bernie, I had not yet received my diagnosis, and nor had she. I had the misconception that Bernie should be able to push through the unboxed chaos and emerge, triumphant. I afforded her no accommodations in living up to the social expectations of her peers. This is why it took me a year to finish a 500-word story. I had to rewrite my own story first, acknowledging my autism and internalised ableism, before I could give Bernie a nudge in the right direction. But I eventually realised Bernie didn’t owe it to anyone to conform. And nor do I.

It’s so important that children’s literature reflects the diversity kids see in their peer groups, and Bernie Thinks in Boxes adds a new perspective to this conversation. I hope Bernie’s story encourages kids to prioritise their needs over social conformity. And equally, I hope it fosters understanding and acceptance of differences. There are so many ways to be a great friend – you just need to think outside the box (see what I did there?).

Bernie Thinks in Boxes

Bernie Thinks in Boxes

by Jess Horn, illustrated by Zoe Bennett, pub. Affirm Press, picture book RRP$ 24.99. Ages 4+

Jess Horn is a children’s author from Sydney, with a background in speech pathology and a fondness for spoonerisms. Her debut picture book, Bernie Thinks in Boxes, is out now.

Bernie Thinks in Boxes has been selected for next year’s Free Prep Bag