30 Jul We live in an age of ‘fake news’ and Australian children are not learning how to check reality

Tanya Notley and Michael Dezuanni report their recent findings from their new research into how young Australians consume and think about news media.

Following a summer of bushfires and during the COVID-19 pandemic, young people have told us they consume news regularly. But they also say they can find it frightening and many don’t ask questions about the true source of the information they are getting.

To our surprise, despite widespread concern about “fake news” and a growing body of evidence about the reach and impact of misinformation, many young people are also not getting formal education about news media at school.

Our research

In February and March 2020, we conducted an online survey of young people’s media use and education. We used a nationally representative sample of more than 1,000 young Australians aged between eight and 16 years.

In our results, we refer to two age categories for analysis: children (8 to 12) and teens (13 to 16).

This repeats and extends a similar survey we did in 2017.

Where do young people get their news?

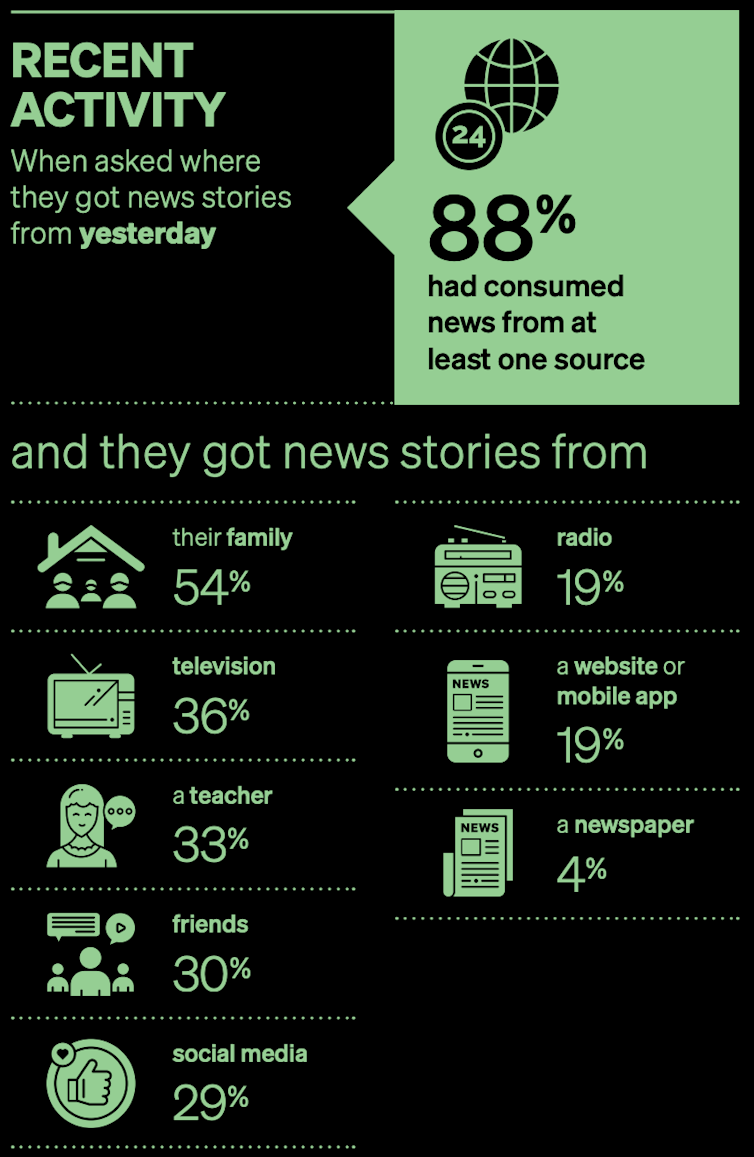

To provide a snapshot of news consumption, we asked young Australians where they got news stories from on the previous day.

We found a clear majority of young people do consume news directly from news sources or they hear about it from people they know and trust.

We found 88% had heard about news events from at least one source, up 8% on 2017. Family were by far the most common source.

For young people, news is social

A striking finding is news consumption has become more social – obtained either through someone they know or social media.

The day before the survey, 70% of young people received news from family, teachers or friends (up 13% from 2017), while 29% got their news from social media (up 7%).

As with 2017, the news consumption practices of children and teenagers are quite different. The greatest difference is in their use of online media, including social media, to get news stories.

While 43% of teens got news from social media the day before the survey, only 15% of children did this. However, the use of social media to get news stories has increased for both age groups when compared with 2017 (it increased 8% for teens and 5% for children).

Young people’s socially orientated news consumption means they will have different experiences and expectations of news media and this may challenge the expectations of older generations.

For example, socially acquired news may not prioritise impartiality or objectivity in the same way traditional news media does. Trust in a source may be developed using different criteria.

What are young people learning at school?

To understand what young people are learning about news media, we asked about young people’s critical engagement with news and the opportunities they have been given to create their own stories in the classroom.

Just one in five young Australians said they had a lesson during the past year to help them decide whether news stories are true and can be trusted. This result was the same for both children and teens. While this figure increased by 3% for children, there was a 4% drop for teens when compared with 2017.

www.shutterstock.com

There was also a drop in the number of young people who said they had had lessons to help them create their own news stories. When it came to teens, 26% had these lessons (down 4% on 2017). For younger children, 29% had these lessons (down 8%).

Information is not being challenged

This lack of news media literacy education in classrooms is troubling.

The number of young people who agree they know how to tell fake news from real new stories increased only marginally from 2017, moving from 34% to 36%.

This very small increase is surprising, given the considerable amount of attention given to this issue by politicians and media outlets over the past few years.

Of further concern, our survey finds a large number of young Australians do not challenge the news they consume, even as they get older.

For example, 46% of young people who get news stories from social media, say they give very little or no attention to the source of news stories found online – this result was the same for children and for teens.

Adults need to talk to kids about news

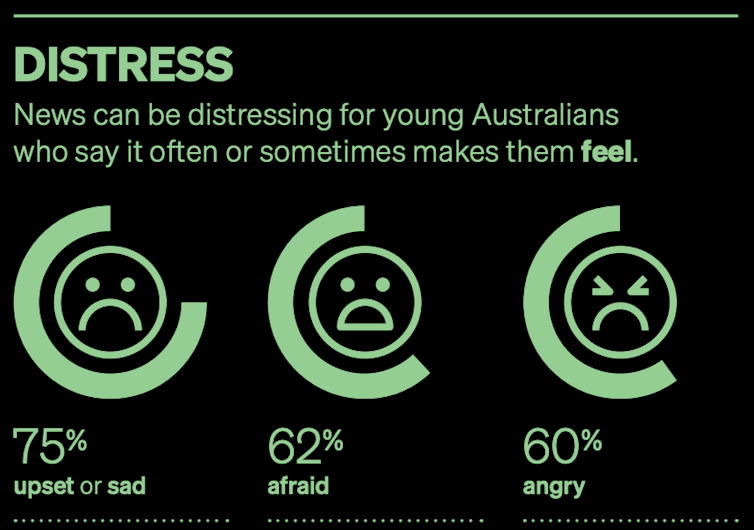

When asked how they feel when they consume news media, the majority of young Australians surveyed reported they often or sometimes feel afraid, angry, sad or upset.

It is possible recent large-scale events such as the summer bushfires and COVID-19 pandemic account for some of these strong responses.

However, they also demonstrate the need for adults to be aware of the impact of news on young people, and to initiate supportive conversations about news.

We also believe these findings suggest media literacy efforts need to take place at home as well as school, with more resources to help parents ensure their children’s news interactions are safe and beneficial.

Why aren’t students learning more about media?

It is not fully clear why Australian students are not receiving widespread critical news literacy education. But our related research finds that while most teachers believe it’s important to support student’s news media literacy, there are many barriers that prevent them from doing this.

These include timetable constraints, an overloaded curriculum, a lack of time for planning and a lack of appropriate training and support.

These barriers must be addressed if teachers are to equip young Australians with the critical skills they need to engage with news media effectively and to discern trustworthy news from disinformation.

Our findings are not all bad news

As we noted above, young people reported more engagement with news in 2020 than in 2017, either directly through news media or through friends, family and teachers.

In addition, 49% agree following the news is important to them and 74% say news makes them feel smart or knowledgeable.

Our findings do suggest, however, there is an urgent need for policy makers and education authorities to increase their efforts around young people’s learning about media.

We believe young people should be receiving specific education about the role of news media in our society, bias in the news, disinformation and misinformation, the inclusion of different groups, news media ownership and technology.

Only then will news play a positive role in young people’s lives and continue to do so in the future.![]()

Tanya Notley, Senior Lecturer in Digital Media, Western Sydney University and Michael Dezuanni, Associate professor, Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.