30 May What lies beneath

Graphic scenes on television in recent times, showing homes crammed floor-to-ceiling with an astonishing amount of stuff is known now as a mental illness. Bronwyn Coulter explains how problems accumulated when she was growing up in a house of hoarders.

I grew up in a house of hopeless hoarders. But it wasn’t always that way. I remember a time when we had a dining room rather than a stacked-to-the-roof storage facility; a bathtub you could put water in, rather than books, televisions and other paraphernalia; a stove you could cook on, rather than just stack stuff on; a fridge with gleaming shelves, not rotting food; and a crisper without a sludgy mess of liquefied fruit at the bottom. I remember being able to see the floor, reach out and touch a wall, and sit at a cleared table with sparkling cutlery instead of precariously balancing on a broken chair with a plate on my knees. I remember when I could invite friends over without feeling ashamed, and when the ring of the doorbell didn’t strike fear into my heart that someone would find out how we lived.

It’s hard to look clean when your bathtub isn’t a bathtub any more

I also remember a time when the other kids at school smelt nice and looked clean, and I didn’t. I was cornered in the playground and told I was “on the nose”, and should take a bath and use deodorant. It’s hard to look clean when your bathtub isn’t a bathtub any more, and you can’t get to the shower because of all the stuff. It’s hard to smell fresh when the dog pees on the small visible portion of hallway floor and it soaks into the floorboards and under the junk where it can never be properly cleaned. It’s especially hard when no-one around you is capable of setting an example of what it means to be clean.

I really don’t know how things got so out of control. It seemed to coincide with my parents losing their parents within a few years. With that came the grief and the responsibility of sorting through personal effects and finalising their estates.

…things other people threw out were retrieved by my father

…things other people threw out were retrieved by my father

Then came my father’s nervous breakdown. I think he wanted to cling to a safer, happier time, surrounded by things that reminded him of his childhood and his parents – things most people would throw out. Unfortunately for us, these things other people threw out were retrieved by my father, who wanted to save them from almost certain destruction.

My environment profoundly affected me. Don’t get me wrong – love was abundant. We were cherished and knew it, and were taught right from wrong and had impeccable manners. I like to think my sisters, brother and I grew into compassionate, imaginative and well-rounded adults. But we were lacking in social skills. We weren’t told how to fit in, or more importantly, how not to stand out, and inevitably all four of us were targeted by bullies.

I stole change I found lying around at home to buy toiletries

To remedy these short-comings I found role models in women of mature years who were my workmates in the hospitality industry. Through their example, I taught myself housework and was eternally grateful for the opportunity to watch and mimic them as they scrubbed, cleaned and dusted. I stole change I found lying around at home to buy toiletries and trained myself to throw stuff away. I learned to change my undies and shower on a daily basis, and that having a clean space around me was essential for my sanity.

I now have a home and children of my own, but the impact of hoarding is still evident. It destroyed my ability to make friends easily – growing up I considered them a liability since they would want to be invited over, so I didn’t make any. I am guarded and shy, can’t make conversation easily and fear social events. I dread the hullabaloo friendship brings, such as invitations to come over that carry an unwritten expectation that the favour will be returned, and the dire prospect of having someone ‘drop in’ unexpectedly.

My relationships have also suffered. I can’t relax and enjoy my own clean home and the company of my husband or kids. I pace around every five minutes to tidy up clothes, toys and sauce bottles (before the meal is even over), ever vigilant against the creeping tide of ‘stuff’.

They are walled in by their stuff, with pathways formed through the junk.

I fear for when my parents have gone. As the eldest child, the task of sorting out their stuff will fall to me. I will be buried alive in paper, old technology, clothes, books and other items that will take me years to sort and throw out. I am terrified of the filth, bugs, spiders and whatever else lies beneath. I dread the guilt that will come from throwing out the things my parents valued so highly that they sacrificed a normal existence to keep.

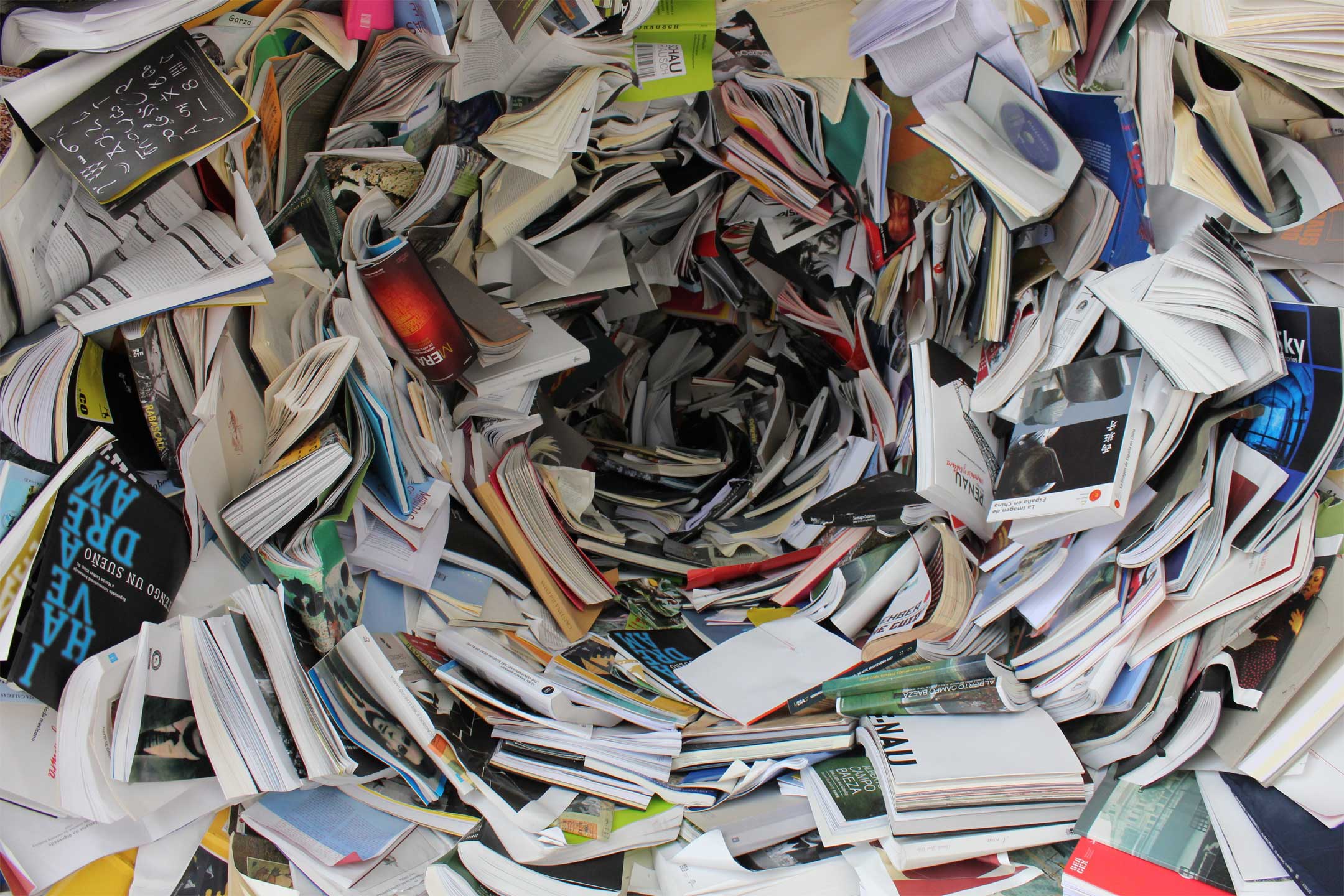

Most of all, I fear my parents’ ‘lifestyle’ could ironically be the cause of their demise. They are walled in by their stuff, with pathways formed through the junk. Progress is slow and painful for them, and they are often injured and bruised when the shored-up walls of stuff inevitably collapse. The risk of fire is ever-present. They are continually frustrated at not being able to find what they need; important documents are swallowed in the mess and are impossible to replace. They are becoming frail, and a fall in this environment would break a hip. I am sad they can’t enjoy their old age in a peaceful, clean and pleasant space, free from decades of emotional baggage manifesting itself as an insurmountable mountain of mess.

So what comes first, the hoarding or the mental illness?

There seems to be a consensus that hoarding is a mental illness. There is a common theme in the many definitions of hoarding: the collection of valueless things (books, magazines, papers, electronic devices, food, clothes – the list goes on and on) and the inability of the hoarder to discard them. So what comes first, the hoarding or the mental illness?

I believe the hoarding is a symptom of the underlying illness, which erodes the ability to connect with others and replaces it with an artificial connection to things.

So much is lost to the hoarder. How can knowing that somewhere in that huge pile of garbage there is a box of spare tap washers compare with the joy of having your grandchildren careering ecstatically and safely around your house – a pleasure my parents have never enjoyed.

Hoarding both relieves anxiety and helps exacerbate it. The more hoarders accumulate, the more insulated they feel from the world and its dangers.

According to the Mayo Clinic, it is not clear what exactly causes hoarding. There are, however, some commonalities among hoarders.

- Age: While severe hoarding is most common in middle-aged adults around the age of 50, their hoarding tendencies began around ages 11 to 15. During these early teenage years, they typically saved broken toys, outdated school papers, and pencil nubs.

- Personality: Oftentimes hoarders struggle with severe indecisiveness and anxiety.

- Genetics: Although hoarding is not an entirely genetic disorder, there is some genetic predisposition involved in the disorder.

- Trauma: Many hoarders experienced a stressful or traumatic event that propels them to hoard has a coping mechanism.

- Social Isolation: Hoarders are often socially withdrawn and isolated, causing them to hoard as a way to find comfort.

So when does clutter turn to hoarding? See Psychology Today’s article

International OCD Foundation Factsheet about hoarding.

Can you help a hoarder?

Helping a sufferer is more complex than just walking into their house, hiring a skip and throwing out all the items they have hoarded. The hoarder most likely would experience negative emotions such as sadness, anxiety and/or anger. Even if the person would permit you to clear out their belongings, the root causes have not been addressed and you would find that the behaviour resumes immediately and the house, garden or garage are soon filled with more items. Sufferers need to be encouraged to seek professional help from their GP who can refer them to the correct practitioner for them.

Illustration by Natasja van Vlimmeren