16 Nov Why these parents have just started their own school in Sydney

–this is part of a long tradition in Australia, writes Nigel Howard and Andrew Bills.

Last week, The Australian newspaper reported some parents have been prompted to start their own schools to give their children the type of education they want.

One of these is Hartford College in Sydney, a new Catholic school with an emphasis on the liberal arts, including classical literature, languages and philosophy. It has about 22 students enrolled, and the founding parents say they want to engage the “whole” child and will have mentors for each student.

Previously when we think of parents taking their child’s education into their own hands, we may think of homeschooling (which is certainly growing in Australia).

But there is a long tradition of parents and local communities starting their own schools if they feel what’s on offer is not suiting their families’ needs.

Ngutu College. Author supplied.

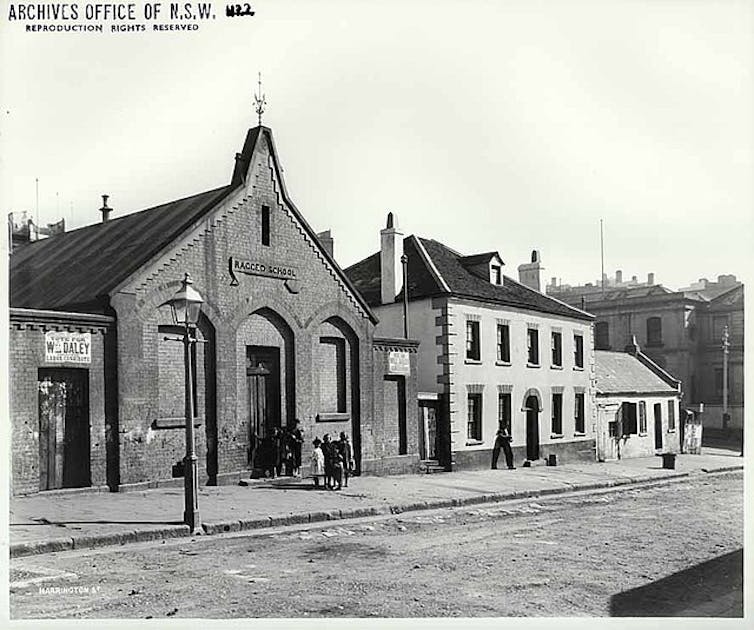

Ragged schools

Before compulsory schooling, Ragged schools appeared in Melbourne as early as 1859.

The idea for these community-funded schools came from England and provided free moral education for poor and homeless children roaming the streets of Melbourne and Sydney.

In the 20th century, parents of children with a disability established schools to meet the specific needs of their children. For example, in 1945, Adelaide’s parents set up the Cora Barclay Centre for children who were deaf from the post-war measles pandemic.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The community schools movement

In the 1970s, parent and community-initiated schools had their heyday.

Coalitions of parents and teachers set up community schools as alternatives to a narrow, paternalistic, exclusionary education.

This was influenced by American education philosopher John Dewey’s ideas about democratic schools and the freedom given to students in Scottish educator A.S. Neill’s Summerhill school. Australian parents and teachers were also emboldened by the civil and children’s rights movements.

But the boom in small, humanist schools was short-lived as state education departments moved to centralisation and standardisation. By the end of the century, community schools had either disappeared or had evolved into places for students who were not progressing in mainstream schools.

Low-fee, faith-based schools

In the 1980s and 1990s, Australia saw an increase in faith-based parent and community-initiated schools.

After a 1981 High Court decision, the federal government began to fund a wider range of schools, including religious schools. Rules that limited the establishment of new schools were also scrapped, further opening up new parent and community-initiated schools.

These schools were “low fee”, mainly Christian schools and usually in growth areas. In the 1990s, parents and leaders from refugee communities also banded together to develop schools that reflected their faith and community.

New specialist schools

Since 2012, the Gonski education reforms have made it even more economically feasible for parents and communities to establish new independent schools.

The federal government now funds 80% of each non-government school’s schooling resource standard. This is an estimate of how much public funding a school needs to meet its students’ educational needs.

This has seen small schools that cater to a specific parent or community need become more common. The largest growth area of these is Special Assistance Schools, which are primarily for students who have dropped out of mainstream school.

But there are also new schools for students with high academic potential, bush schools, sports schools, performing arts and music schools, science-based schools and sustainable schools.

How do parents create a new school?

Not every vision for a new school is successful. Setting up a new school takes leadership, time, commitment, determination and money.

The school must be able to satisfy the state’s school accrediting authority that they have premises, a governance structure with a board, and will be able to deliver a curriculum and meet safety and protection requirements for staff and students.

For the last four years, we have been researching the development of a new Adelaide school, Ngutu College. It was established by former state school principal and Kamilaroi Man, Andrew Plastow, in response to teacher and community concerns.

It describes itself as having:

Aboriginal cultures as its soul, children as its heart and the arts as its spine.

It took 18 months from the initial discussions with the community to open its classroom doors to students in 2021.

Ngutu has 230 students, of which 44% are Indigenous. As it expands to Year 12, it will be capped at 350 students to retain its community focus.

Hartford College and Ngutu College are worlds apart in their vision of education, but both are small schools driven by communities wanting to do the best for their children.

Ngutu College/Author supplied.

What does this mean for the mainstream system?

Parents and communities are setting up their own schools because they feel their needs are not being met in the mainstream system, which has increasingly been tied to narrow ideas of “success”.

The strength of public education is the interaction between children, young people and their wider community. The more separate, specialised schools that are set up, the more the public loses these students, parents and communities.

In an ideal world, the local public school is able to provide for diverse students and communities. This means schools need to be open and responsive to the needs of students. This means parents and communities also need to be involved in shaping how their schools are run, and their children are educated.![]()

Nigel Howard, Research associate, Flinders University and Andrew Bills, Researcher into Educational Leadership and Policy, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.