27 Jun Partners in Time: sharing the highs and lows of parenting

Damon Young and his wife have decided to share the highs and lows of parenting and of work.

Last year, we brought our baby daughter home from the hospital. Life was part euphoria, part coma as we juggled nappies, baths, meals, washing, and our curious toddler.

We received the usual congratulations, well wishes, and goodwill. But we also received gasps of astonishment: ‘What? You came home from the hospital after one day?’ Many assumed we were kicked out of the wards (not true) or that we were naive (possibly).

The simple truth was this: home was precisely where we wanted to be. And more importantly, my wife knew she was coming home to support: not only from her mum or nurses and midwives but also from me.

I could play with our toddler son, make meals, wash the dishes, change the baby’s nappies, and generally be a dad. My son received plenty of attention (without being smothered). My wife didn’t go quite as bananas all alone—she has me to make her do that. Put simply, it’s called ‘teamwork’. It can be maddeningly dull, but it’s what marriage is about.

Of course, teamwork comes in different shapes and sizes. For some, it’s the traditional model: Dad off to work, Mum at home. For others, it’s the reverse: Dad uses a formula or expressed milk, and Mum heads off to the office.

This approach certainly has its benefits. It affords specialisation, so each partner gets to hone their skills instead of dividing their energies. This can be essential for self-identity – watering down your professional or parenting self can be painful.

But it also has its drawbacks.

And the most obvious is empathy: after a while, it becomes very hard for the daily office worker to understand the sweet tedium of daily kid-wrangling. The stinking bodily fluids, the sickness, the boredom, or the moments of sublime, quiet perfection – these become a little more abstract. At the same time, it’s sometimes difficult for a stay-at-home parent, even when they’ve been in the workforce for decades, to recall the full experience of professional anxieties and hopes, of the rush and congratulation of a job well done, or its frantic opposite.

Over the years, these differences can become distances: it becomes increasingly difficult for some couples to understand one another; to grasp their respective achievements and sacrifices. This is genuine teamwork, but after a while, it can feel as if you’re playing for different teams.

And this, at least in part, is why we’ve chosen to do otherwise. We both work part-time and earn less than the average wage between us. We’re not poor, but we’re a far cry from most of our middle-class peers. No home of our own, no new clothes, no private schools. But our gamble – and this is precisely what it is, no mistake – is that this will make our marriage stronger and more enduring. There will undoubtedly be other stresses, as they’re part of life. Our hope is that we’ll have forged the bonds to face our anxieties together.

We also hope it’ll be better for our kids. My son and I go shopping, play, argue, and go to cafes—we do all the things mums do with their kids. And I’ll do the same with my daughter. When they’re grown, hopefully, my kids won’t see a stranger but a familiar, perhaps frustrating, figure: the clumsy, verbose, excited father they grew up with.

Now, my point isn’t to criticise parents who’ve adopted the traditional model. It has countless benefits, and often, couples have no choice. For others, it’s what they excel at, and I’ve no business quibbling with their expertise. Some days, I long to be a full-time something – I feel like an amateur, failing in my career and as a father. But what’s crucial to me is what might be called the ‘domestic imagination’. It’s vital that we try to envisage new ways of collaborating and caring, new kinds of marriage and parenthood. This might entail sacrifices of income, security, recognition and comfort.

It will also require a change in the attitudes of government and industry: supporting secure, flexible employment, which doesn’t penalise employees for having families and wanting to spend time with them.

All in all, parenting will always be a diverse gig. And so it should be: homogeneity is usually a sign of social sickness.

For the lucky few who are able to choose, the important thing is liberty of spirit: freely, boldly, and creatively inventing the best family life we can within life’s constraints.

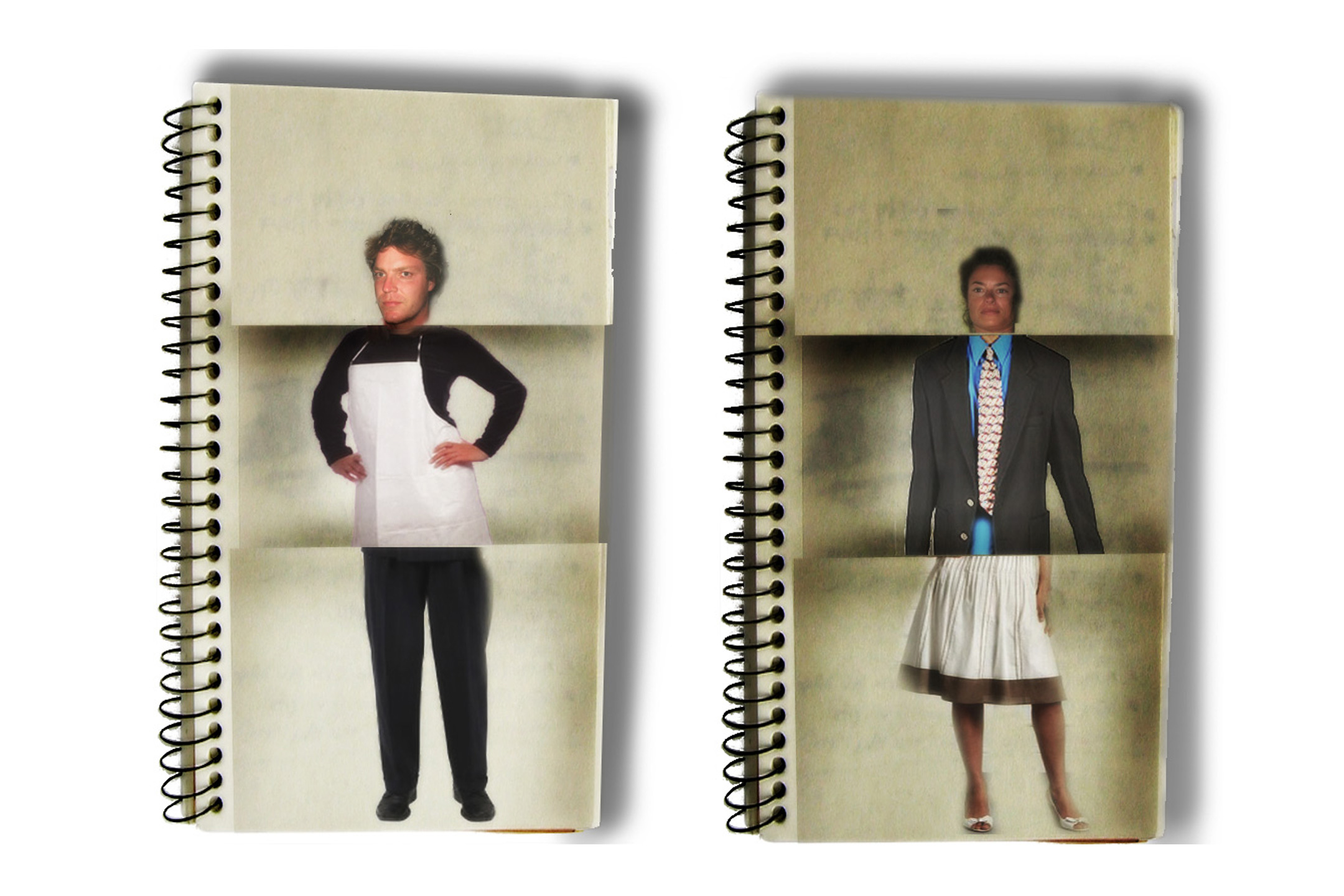

Illustration by Darby Hudson