22 Sep A child’s right to be heard

After a parent is killed due to domestic violence, writes Hannah Morrice, children aren’t given enough opportunity to express their opinions on decisions that directly affect their lives

Although our country is considered a prosperous one – Australia is the 12th largest economy in the world – we are ranked as one of the lowest rich countries when it comes to child wellbeing. In fact, Australia is rated 32nd out of 38 countries.

Australia ratified the CRC in 1990. This means we have a duty to ensure all children in Australia enjoy the rights set out in it.

This includes Article 12, which determines that children should be given the opportunity to express their views in all matters concerning them and that these views should be given due weight.

Seen but not heard

Allowing children to express their views on matters that affect them is not only a right they should be afforded but also a critical component to improving child wellbeing.

However, our research regarding children and young people bereaved by domestic homicide suggests Australia’s child protection and family law system does not have a consistent framework for incorporating children’s views into practice.

In many ways as a country, we continue to practice within statutory systems that embed the historic cultural attitude “children should be seen and not heard”.

We interviewed Australian young people and adults who had lost a parent due to domestic homicide when they were under the age of 18. We also interviewed carers, family, friends and professionals supporting these children and their families.

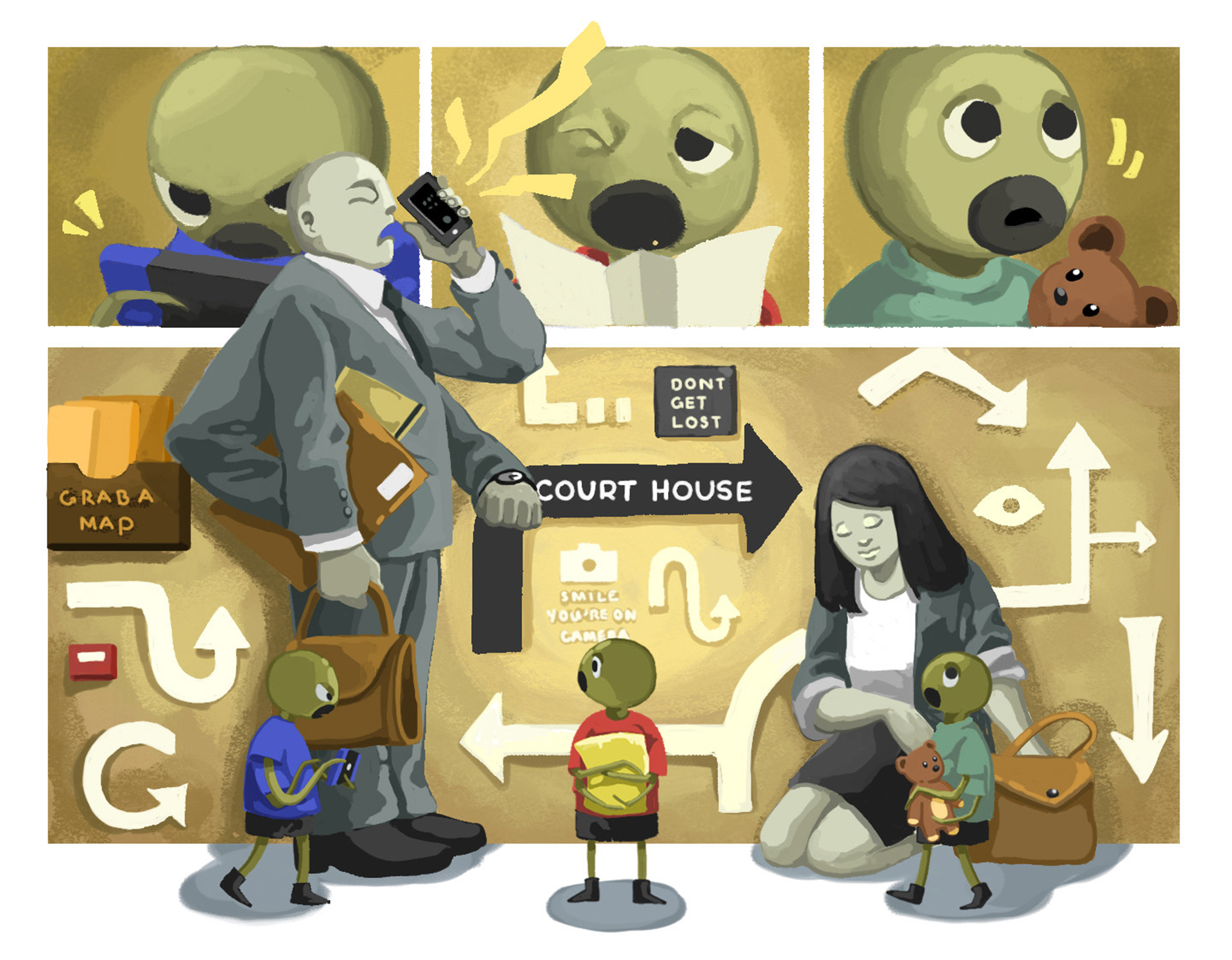

In the aftermath of the murder, many children and young people – most of them now adults – felt powerless. They did not feel like they had an opportunity to express their views on important decisions that directly affected their lives.

Questions about who they would live with and where, or how much contact, if any, they would have with the offending parent were usually left up to the decision-making adults in their lives.

On top of this, participants found that the statutory systems in charge of making these decisions were not set up to systematically listen to, take seriously and act on the opinions of the children themselves:

“We sort of got pushed and shoved until the courts came to a conclusion about where we were going to end up….. And eventually they – ‘they’ being the courts – came to the decision to put me and my sister with my dad’s [family member].

“And then you’re suddenly told that not only have you lost both parents, but you’ve also then lost everything that you know, your existence and your stability.

“We went through a myriad of court hearings…all very, very confronting during a very traumatic time, I guess, with very little advocacy, on our part for what we actually wanted and the notion that we should be separated when effectively [my sibling] and I were the only family that we had.”

A legal system by and for adults

Hearing these accounts led us to ask what exactly happens to a child after becoming bereaved by domestic homicide in Australia? And when the courts become involved, what opportunities do children have to participate in proceedings?

The answers to these questions are far from straightforward.

Australia’s legal system is complex in both Federal and State jurisdictions, which deal with a variety of child protection and family law matters. Understanding how to navigate these systems is incredibly difficult.

Our team found a general lack of consistency across these systems that confuses even long-time professionals as to what is best practice.

For a child who may have lost their two most logical advocates in life – their parents – there is little hope of understanding how to deal with a system that has been designed by and for adults.

Just to illustrate how complex Australia’s legal system is when it comes to a case of domestic homicide, let’s take a closer look.

Each Federal, State and Territory court is governed by its own legislation. And the process differs across these various court systems for how and when to listen to a child in the court.

In Victoria, for example, there are two models of participation with a lawyer that are available for child protection cases.

The first model is direct representation where the child is able to instruct a lawyer and the lawyer will then argue on behalf of the child’s view. The second, best interest representation, requires a lawyer to take a position with regard to what they consider is in the best interests of the child.

In Victoria, all children aged 10 and above involved in child protection proceedings must be legally represented. This will mostly be through direct representation unless the court determines that they do not have the maturity to give instruction.

Children under 10 may be appointed a ‘best interests lawyer’ in exceptional circumstances. However, this is not common: many children under 10 are not legally represented.

And when children are appointed a ‘best interests lawyer,’ current legislation provides little guidance about the role and responsibilities of this lawyer. For example, there is no guidance on how often the ‘best interests lawyer’ should meet with the child, where these meetings should take place and for how long.

In the Federal family law system an Independent Children’s Lawyer can be appointed in certain circumstances. Only with recent amendments to Family Law is it now required for an Independent Children’s Lawyer to meet with the child. Importantly, when, how often and how meetings with the child take place are still at the discretion of the lawyer.

Recognising children’s capacity

Current guidelines for independent children’s lawyers describe that children’s “age, developmental level, cognitive abilities, emotional state and views” inform the lawyer’s involvement with the child.

However, we know that professionals structurally underestimate children’s capacity to talk about traumatic experiences and what they need.

Combine the complexities of State and Federal systems with limited guidance for individual professionals and you get a potent mix for inconsistent and limited opportunities for children to participate in crucial decisions about their lives.

While there are certainly positive attempts to incorporate children’s views in legal representation, how children’s views are acted upon in the decision-making process is ultimately at the discretion of the professionals working on behalf of the child.

An overarching, unified best practice framework specifically for children affected by domestic homicide could go some way to improving practice standards and quality of service provision.

While new guidelines to accompany the recent Family Law amendments for Independent Children’s Lawyers have not yet been finalised, we hope they will take a child-rights approach, and build on important resources that have already been developed in this area, including the Child Participation Framework developed by 54 Reasons Australia (formally Save the Children).

Without a cultural norm to embed the principle of Article 12 in Australian law, it is likely that paternalistic attitudes, differences in professional knowledge of child development and lack of training weaken a child’s opportunity to be heard.

The accounts of people bereaved by domestic homicide and those who support them tell us children have very limited opportunities to make decisions about their own future. This gap in system-specific best practice can and does result in compounding trauma for this unique group of children and young people.

If we are to truly support children in the aftermath of domestic homicide, a social support and legal system must be designed in a way that is child-rights based, young-person centric and aligned with a genuine cultural norm that children’s views should be heard and respected.

B Hannah Morrice, University of Melbourne and Professor Eva Alisic

This article has been written in collaboration with Elicia Savvas, Associate Director, Child Protection, Victoria Legal Aid and Rebecca Burdon, Director and Principal Lawyer at Rebecca Burdon Legal and Consulting.

This article is part of a series on the impact of domestic homicide on children and young people. While there are usually one or two authors mentioned, the whole research team and several people with lived experience have contributed. The illustrations have been hand drawn by Thu Huong Nguyen (Abigail). The research report contains further information.

Are you looking for support? In Australia, good places to start are Kids Helpline, Life Line, Beyond Blue and 1800 Respect. These are all free of charge. You can also contact your doctor (GP) to discuss a subsidised Mental Health Treatment Plan, and you may be able to access counselling through your employer’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP) or your TAFE/university’s counselling services. You may also be eligible for support, counselling or financial assistance through your state or territory Victims of Crime service.

Banner: Thu Huong Nguyen (Abigail). This article was first published 26 November 2023 on Pursuit. Read the original article.