03 Mar Not as simple as ‘no means no’: what young people need to know about consent

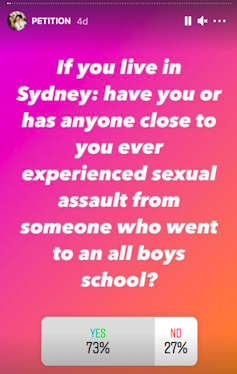

A recent petition circulated by Sydney school girl Chanel Contos, Jacqueline Hendriks writes, called for schools to provide better education on consent, and to do so much earlier.

In the petition, which since Thursday has been signed by more than 5,000 people, Contos writes that her school

… provided me with life-changing education on consent for the first time in year 10. However, it happened too late and came with the tough realisation that amongst my friends, almost half of us had already been raped or sexually assaulted by boys from neighbouring schools.

So, what core information do young people need to know about consent? And is the Australian curriculum set up to teach it?

What’s in the curriculum?

This is not the first time young people have criticised their school programs. Year 12 student Tamsin Griffiths recently called for an overhaul to school sex education after speaking to secondary students throughout Victoria. She advocated for a program that better reflects contemporary issues.

Australia’s health and physical education curriculum does instruct schools to teach students about establishing and maintaining respectful relationships. The resources provided state all students from year 3 to year 10 should learn about matters including:

- standing up for themselves

- establishing and managing changing relationships (offline and online)

- strategies for dealing with relationships when there is an imbalance of power (including seeking help or leaving the relationship)

- managing the physical, social and emotional changes that occur during puberty

- practices that support reproductive and sexual health (contraception, negotiating consent, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections and blood-borne viruses)

- celebrating and respecting difference and diversity in individuals and communities.

Despite national guidance, there is wide variability in how schools interpret the curriculum, what topics they choose to address and how much detail they provide. This is further compounded by a lack of teacher training.

A study of students in South Australia and Victoria, along with repeated nationwide surveys of secondary students, have shown young people do consider school to be a trustworthy source of sex education. But most don’t believe the lessons have prepared them adequately for relationships and intimacy.

They want lessons that take into account diverse genders and sexualities, focus less on biology, and provide more detail about relationships, pleasure and consent.

The national curriculum also stops mandating these lessons after year 10 and many year 11 and 12 timetables are focused on university entrance exams or vocational learning opportunities. This means senior students have limited opportunity to receive formal sex education at a time when they really need it.

So, what should young people know about consent?

The term “consent” is often associated with sex, but it’s much broader than that. It relates to permission and how to show respect for ourselves and for other people. Consent should therefore be addressed in an age-appropriate way across all years of schooling.

Shutterstock

The most important point about consent is that everyone should be comfortable with what they’re engaging in. If you are uncomfortable at any point, you have the right to stop. On the other side, if you see someone you are interacting with being uncomfortable, you need to check in with them to ensure they are enthusiastic about the activity, whatever it may be.

In the early years, students should be taught how to affirm and respect personal boundaries, using non-sexual examples like whether to share their toys or give hugs. It is also important they learn about public and private body parts and the importance of using correct terminology.

In later years, lessons should consider more intimate or sexual scenarios. This also includes consent and how it applies to the digital space.

Older students need to learn sexual activity is something to be done with someone, not to someone. Consent is a critical part of this process and it must be freely given, informed and mutual.

Consent isn’t about doing whatever we want until we hear the word “no”. Ideally, we want all our sexual encounters to involve an enthusiastic “yes”.

But if your partner struggles to say the word “yes” enthusiastically, it is important to pay attention to body language and non-verbal cues. You should feel confident your partner is enjoying the activity as much as you are, and if you are ever unsure, stop and ask them.

Often this means checking in regularly with your partner.

Young people also need to know just because you have agreed to do something in the past, this does not mean you have to agree to do it again. You also have the right to change your mind at any time — even partway through an activity.

It’s not as simple as ‘no means no’

The most recent Australian survey of secondary school students highlighted that more than one-quarter (28.4%) of sexually active students reported an unwanted sexual experience. Their most common reasons for this unwanted sex was due to pressure from a partner, being intoxicated or feeling frightened.

We should be careful not to oversimplify the issue of consent. Sexual negotiation can be a difficult or awkward process for anyone — regardless of their age — to navigate.

Some academics have called for moving beyond binary notions of “yes means yes” and “no means no” to consider the grey area in the middle.

While criminal acts such as rape are perhaps easily understood by young people, teaching materials need to consider a broad spectrum of scenarios to highlight examples of violence or coercion. For example, someone having an expectation of sex because you’ve flirted, and making you feel guilty for leading them on.

When it comes to sexual activity, we should be clear that:

- although the law defines “sex” as an activity that involves penetration, other sexual activities may be considered indecent assault

- a degree of equality needs to exist between sexual partners and it is coercive to use a position of power or methods such as manipulation, trickery or bribery to obtain sex

- a person who is incapacitated due to drugs or alcohol is not able to give consent

- wearing certain clothes, flirting or kissing is not necessarily an invitation for other things.

We should also challenge gender stereotypes about who should initiate intimacy and who may wish to take things fast or slow. Healthy relationships involve an ongoing and collaborative conversation between both sexual partners about what they want.

Consent is sexy

A partner who actively asks for permission and respects your boundaries is showing they respect you and care about your feelings. It also leads to an infinitely more pleasurable sexual experience when both partners are really enjoying what they are doing.

It is important that lessons for older students focus on the positive aspects of romantic and sexual relationships.

They should encourage young people to consider what sorts of relationships they want for themselves and provide them with the skills, such as communication and empathy, to help ensure positive experiences.

More information about consent:

- the “Consent is as easy as FRIES” is a useful model

- this viral YouTube clip shows how consent is as easy as a cup of tea

- the parent resource Talk Soon. Talk Often. provides some ideas on how to start a conversation about consent with your child

- Headspace and KidsHelpline also has some useful resources for young people.

Jacqueline Hendriks, Research Fellow and Lecturer, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.